Bass To Infinity: An Interview with Buster Williams

With nearly six decades in the business, Buster Williams has just about seen it all. He’s worked with some of the world’s best instrumentalists (Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, Sonny Stitt, and Gene Ammons to name a few) and the world’s best vocalists (Nancy Wilson, Sarah Vaughan, Dakota Staton, and Carmen McRae, to name a few). As you can imagine, he’s got some great stories to tell.

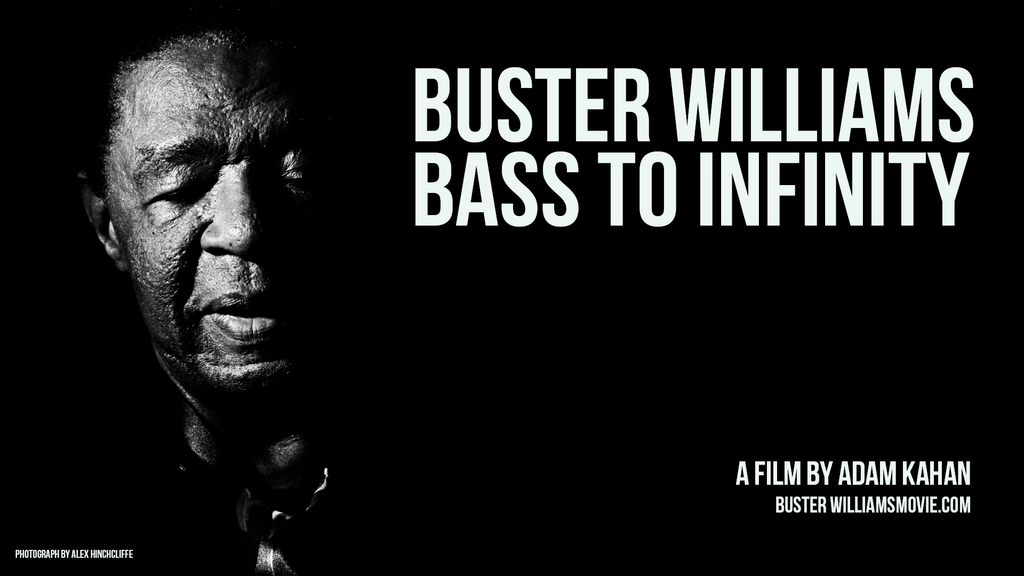

Lucky for us, Williams is the subject of an upcoming documentary by filmmaker Adam Kahan entitled Bass to Infinity. The film covers his beginnings in Camden, New Jersey – where his multi-instrumentalist father taught him the bass – through his current work and everything in between. It includes incredible animated stories as well as interviews and jams with fellow musicians. The film is currently raising money to finish the editing process via Kickstarter. Fans who back the documentary can get rewards ranging from an advance of the film to bass lessons with the master himself to executive producer credits.

We caught up with Williams before his gig at Blues Alley in Washington, DC to get the scoop on his career, what he learned from working with singers, and the documentary.

Do you feel the jazz scene was more vibrant back in the ’60s and ’70s?

I believe it was. Of course, everything has to do with perception, but for me, I was brand new at it and it was all exciting. It seemed that there were many more opportunities to play with your mentors than there are now. There were more clubs available. And there was more of an enthusiasm for the music because you could hear it on the radio in those days, which is kind of difficult to do now.

Who would you consider some of your mentors?

My first mentor was my father. He was my teacher. Then I went out on the road with Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt right after I graduated from high school. Before that, while I was still in high school I was playing with Jimmy Heath, so I would consider him a mentor, too. Then I got to meet Ray Brown. All of these giants that I got to play with were my mentors. Not just instrumentalists, but vocalists, too. I was with Sarah Vaughan for two years, Betty Carter for a number of years. I’ve learned things from all of these people. Benny Golson has been a mentor of mine since my early high school days. So, I learned from all of these great masters.

I wanted to ask you about a Gene Ammons story I read where he left you holding the bag after a gig. What happened?

He stranded the band in Kansas City after we played two weeks. There was no money, according to him. We were supposed to go to Chicago to open up the club McKee’s for 16 weeks. We had a meeting the last night of the gig and agreed that he would go on to Chicago and get a draw then send us the money to come to Chicago. And he never did. [laughs] Fortunately we were able to play another week as a trio at the club we had been playing at. That’s how we got the money to get home.

I know you eventually worked with Gene again. How did you reform a relationship after that?

It’s interesting because I sued him through the American Federations of Musicians and I got all my money. Right after he stranded us, he got arrested and was put in jail. Then he was supposed to be going away for a long time but things were worked out and he got out of jail. The first thing he did when he got out was call me. He said, “J.R., I’m home. I want you to come do a record with me.” And I said sure. He and Sonny Stitt were like fathers to me. He came to New York and we did a record called “The Boss is Back.” The album cover has him coming out of the doorway of an airplane. As far as the relationship is concerned, we never even talked about what went down.

You mentioned Ray Brown as one of your mentors. You got to know him pretty well?

Yeah, pretty well. He had spent all of those years with the Oscar Peterson Trio, and he decided to leave the trio and settle in Los Angeles. At that time I was living in Los Angeles because I moved out there with Nancy Wilson. I started with her in 1965. In March, I married my childhood sweetheart and Nancy was her maid of honor. As a wedding gift, Nancy moved us out to California. She was moving her operation from Chicago to California and she wanted me to come out with her. I was there from April of ’65 to November of ’68. In that time, Ray Brown settled in Los Angeles. Of course, when he arrived, they gave him the key to the city. Fortunately, I had met Ray Brown and we were friends so he started calling me for all of the work he couldn’t do, which was a whole lot of work. He kept me quite busy.

Did you get to know a lot of the bass players on the scene? I figure it could be hard when everyone has a gig and there’s only one bassist on the gig.

There’s one bass player on the gig, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get to know other bass players. In those days, it was very interesting. Jazz festivals were really jazz festivals. We all lived in New York, but you wouldn’t see each other very much. You’d think we’re all in the same city and could see each other all the time, but we were all working. On jazz festivals, that’s where everybody would be. These were festivals in the States as well as Europe and Japan, so that was kind of like the gathering place. You’d travel to the North Sea Jazz Festival and see friends that live just blocks away from you in New York. That was in the days when jazz festivals were jazz festivals. It’s not that way anymore.

Festivals today use jazz as a pretty loose term. Do you think they’re just using it?

Exactly. The word jazz sells, but they swear that jazz itself doesn’t sell. They use the word jazz to sell anything. I don’t agree with all that stuff. It’s all economics and everyone is nudging each other for power.

You spent so much time with Nancy Wilson and all these singers. What did you learn from being a sideman to them?

Oh, it was incredible. Now take Betty Carter. Betty Carter had such control that she could sing so slow and so far behind the beat that it was incumbent upon me to be in control of myself. I couldn’t let a slow tempo of the fact that she was singing so far behind the beat throw me off. So I learned control with Betty Carter. With Sarah Vaughan, I learned to play in tune. She had perfect pitch and if I played anything out of tune, she would hear it. All of these singers, they love the bass player. I’ve found that great singers listen to the bass player. So I would do duos a lot with all of these singers: Sarah Vaughan, Betty Carter, Nancy Wilson, Carmen McRae. I learned the importance of lyrics. If a song has a lyric, learn it because it will have an important role in how you interpret the song. I learned the importance of melody, and that it’s not just something to get out of the way so you can play your solo. I couldn’t be the artist that I am if it were not for these singers. I was fortunate enough to play with all of these singers who were musicians. Betty Carter played piano and wrote her own songs. Of course, Sarah Vaughan was a great pianist. Carmen McRae, also. They could sit down and accompany themselves. Dakota Staton, I learned the real meaning of show business. She really knew how to sequence her songs so that no part of the performance was a letdown. From the beginning to the end, the performance had a curve and a shape to it. That’s just some of the things I learned from the singers. Discipline, self-control, playing in tune, patience, and never losing focus.

Oh, it was incredible. Now take Betty Carter. Betty Carter had such control that she could sing so slow and so far behind the beat that it was incumbent upon me to be in control of myself. I couldn’t let a slow tempo of the fact that she was singing so far behind the beat throw me off. So I learned control with Betty Carter. With Sarah Vaughan, I learned to play in tune. She had perfect pitch and if I played anything out of tune, she would hear it. All of these singers, they love the bass player. I’ve found that great singers listen to the bass player. So I would do duos a lot with all of these singers: Sarah Vaughan, Betty Carter, Nancy Wilson, Carmen McRae. I learned the importance of lyrics. If a song has a lyric, learn it because it will have an important role in how you interpret the song. I learned the importance of melody, and that it’s not just something to get out of the way so you can play your solo. I couldn’t be the artist that I am if it were not for these singers. I was fortunate enough to play with all of these singers who were musicians. Betty Carter played piano and wrote her own songs. Of course, Sarah Vaughan was a great pianist. Carmen McRae, also. They could sit down and accompany themselves. Dakota Staton, I learned the real meaning of show business. She really knew how to sequence her songs so that no part of the performance was a letdown. From the beginning to the end, the performance had a curve and a shape to it. That’s just some of the things I learned from the singers. Discipline, self-control, playing in tune, patience, and never losing focus.

Do you see a certain era or mentor that shaped your playing the most?

It would be hard to say who shaped my playing the most. My career, fortunately, has been like going up a ladder. If I’m on the fifth rung of the ladder, it’s because I learned my lessons on the first, second, third, and fourth rungs of the ladder. So I can’t say that the fifth rung is doing more for me than the first four. Everything was a stepping stone that pushed me on to the next step. I had great experiences with Miles Davis. I learned from Miles by just being in his presence. He never talked about the music. Our conversations were always about something else. When we got on the bandstand, he was a teacher bar none by the way he approached things. By the way he used space, and by the way he allowed the band to be part of the performances. Whatever he did was shaping the music as well as being part of the shape. It was wonderful.

In the early ’70s you took up Buddhism and started chanting. Do you feel like it helped shape the music from that era?

There’s no way that it can’t. Chanting Namu My?h? Renge Ky? creates a pure human revolution – a real transformation in your life that not only changes your reaction to things but your perception of things. I used to see myself, if you asked me who I was, as a musician. But through chanting, if you ask me now who I am, I’m a human being. It changed my perception of who I am and what role I play in this world and in this life. It far surpasses just being a musician. Playing music is what I do, that’s now who I am. I realize that who I am is part of the human race and that I can be a true asset to the human race. That realization gives me a much broader viewpoint and a greater appreciation for life itself. Through practicing with the organization Soka Gakkai International, I can go all over the world and meet people that chant Namu My?h? Renge Ky?. We can’t speak the same language, but we can practice Buddhism together because it’s rooted in creating unity between human beings and creating happiness for each other. I can see my effects on other people regardless of what their walks of life may be. It’s a true peace movement and it has so many advantages to it. There are no limitations to this practice. You don’t have to be this person of that person or this way or that way. Anybody can chant Namu My?h? Renge Ky? and become a happy person by creating victories where you didn’t see victories as possible.

I know you have a new documentary coming out. When can fans expect that?

The filmmaker started a Kickstarter to raise money to finish the editing because the film is done but he’s engrossed in the editing of it. His aim is to have it presented at the top of next year. There’s a lot of stuff in this documentary. I’m really excited about it. The animations are really nice, too. The documentary is called Bass to Infinity.

Was there anything revealing in the process? Were there questions that made you think about aspects of your life differently?

Questions always make me think about things in a certain way. I can’t count how many interviews I’ve done and how many times I’ve had to answer the same questions. I like interviews. Some are better than others, but there’s a challenge to them. Do I just say, “All of these answers are in my bio – go read it.” [laughs] Or do I find a new segment in coming up with the answer? I like an interview that helps me reveal not only myself to you, but reveals myself to me. So I would have to say that the whole process of making this film was very interesting because it involved on location, interviews, getting my insights on things, and the way I saw things then versus how I see them now. It was also a revelation of all the stories I have. I can write volumes with these stories. So that’s the other thing, my friends have been telling me for years that I need to write a book. The only thing that has kept me from writing a book is that I don’t want to do the writing. I can do the talking, and I have people who are willing to listen and do all the writing and editing. I think I’m going to go ahead and do that, too, so don’t be surprised if a book is coming out soon, too.