Stories Behind the Songs: Kenny Passarelli

Kenny Passarelli’s place in music history was cemented when he co-wrote Joe Walsh’s “Rocky Mountain Way,” but that just scratches the surface of his career. He also worked with Elton John, Hall and Oates, Stephen Stills, Tommy Bolin, Dan Fogelberg, Yusuf Islam (Cat Stevens), and more. Naturally, he has more than a few stories to tell.

The bassist grew up in Colorado and started on classical trumpet before picking up the four-string. Little did he know how much of his experiences would transfer to the rock world. “I switched to bass when I was 15 or 16,” he says. “Everyone wanted to play drums or lead guitar in 1965 and 1966, so I started playing the bass. My education was on trumpet, and I had a great teacher in a great organization here in Denver. We’d record our winter concerts every year, so there was the foundation for the future for me more than I ever realized. I had this head start on understanding that when the red light goes on, don’t make any mistakes. Because of my ear training and the desire to learn, I taught myself using the first four strings of the guitar and listening to The Animals. I had such great ear training that it was just getting the dexterity.”

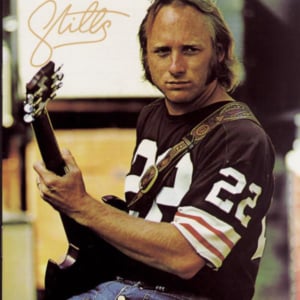

Situated at the edge of the Rockies, Passarelli began to make a name for himself in the local scene. It wasn’t long before a big name came to town and changed his life, although things didn’t come to fruition immediately. “I quickly was doing quite well with it early. There was a music store in town, and they said, “Stephen Stills is coming into town, and he’s looking for a bass player. He’s got this new project.” I had seen Buffalo Springfield on their tour, and I was a fan of the Super Session records, so I knew who he was. I met him at the place where the cover for his solo record was taken. We jammed together, and he played me the acetate of the CSN record. It changed my life. After we jammed, he said, “I’m looking for a bass player for my new project Crosby, Stills, and Nash. We have our first gig at something called Woodstock… I don’t know exactly what it is.” I was already in a band that was signed to ATCO. Stills offered me the gig, but little did I know I had an illness that prevented me from joining him. I didn’t get the gig – Gregory Reeves did – but that was my first acknowledgment that I could really do this for a living.”

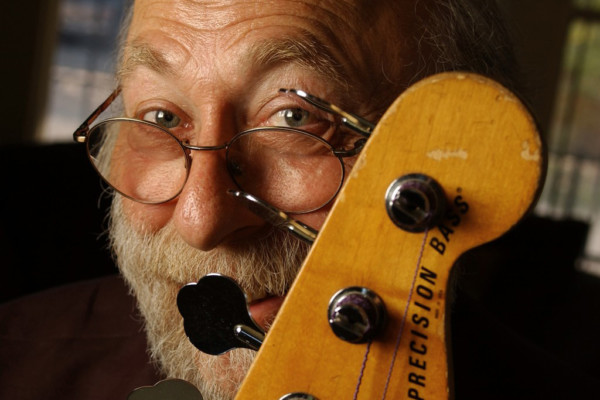

While he played an assortment of basses in his career, Passarelli is known for being an early adopter of the fretless Precision bass. “I had started playing the fretless bass with Joe,” he explains. “I acquired a reputation for playing it. “Rocky Mountain Way” is not fretless, but everything else on the record The Smoker You Drink is fretless. I’m currently playing a Pat Wilkins custom fretless that’s exactly like my ’72 P bass. It’s white with a maple neck that’s tapered like a Jazz. It sounds incredible. Pat is a wonderful guy.”

Networking, reliability, and incredible bass playing led Passarelli to play with the biggest stars in the world in some of the biggest venues in the world. Here are some stories behind the songs that got him there.

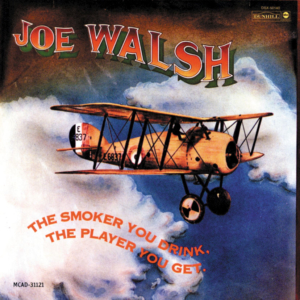

1. “Rocky Mountain Way” – From Joe Walsh’s The Smoker You Drink, the Player You Get (1973)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

It’s really a Joe Walsh song. We were credited because Joe loved my bass part. Really, it’s the three of us. Rocke Grace didn’t play on that record. Rocke was hired on as a keyboard player because, on the two records, Joe Walsh and Joe Vitale played keyboard. They needed someone to play the parts live. Walsh, I think just out of the goodness of his heart and not knowing it would be a big hit, gave Rocke credit.

It’s really a Joe Walsh song. We were credited because Joe loved my bass part. Really, it’s the three of us. Rocke Grace didn’t play on that record. Rocke was hired on as a keyboard player because, on the two records, Joe Walsh and Joe Vitale played keyboard. They needed someone to play the parts live. Walsh, I think just out of the goodness of his heart and not knowing it would be a big hit, gave Rocke credit.

Joe came up with the riff, and Joe Vitale and I came up with the feel. We were all living in Colorado, so it was really a Colorado song. Joe was at Kent State, so it was politically motivated, too. [On the road we would change the lyrics to] say, “Bases are loaded and Nixon’s at bat. It’s time to change the batter.” Those were the things we were doing because we were on the road 200 days a year with Barnstorm. We were in the middle of the early ’70s, so that was the times and that song represented the times. It was completed at Caribou [Ranch studios]. We did the basic track in Miami – bass, drums, and guitar – then we brought it back to Caribou to do vocals and overdubs.

I used Joe’s Jazz bass on that. If you listen to it real close, there’s one thing I do where I play this weird little sound where you can tell it’s not a fretless bass. People say, “What’s your approach to bass?” Well, it’s called a conversation. I’m listening to the lyrics, and I’m listening to the instruments, and I’m conversing with the low frequencies. It sounds like it could almost be a mistake. Nobody plays that bass part the way I play it. I never follow the [hums the post-chorus riff.] I never play that. When I’m doing the verse part, it’s not a complete straight pedal. You have to listen very carefully. It allows the guitar to do something a little bit different. I don’t think I’ve heard anyone play it exactly the same way I played it.

We had a direct from the bass, and I used an Ampeg B-15 for all the Joe Walsh stuff. The combination of the two sounds is what we’d use and once I learned that, I would suggest it for all my sessions.

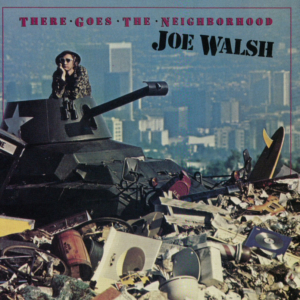

2. “A Life of Illusion” – From Joe Walsh’s There Goes the Neighborhood (1981)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

My father loved Mariachi music, so I was listening subliminally and hearing harmonies. People say, “Geez, ‘Life of Illusion’ is kind of a Latino bass line,” and when you put trumpets on there it’s a Mariachi style. That’s probably from the influence of my father’s love for Mexican music. At a very young age, I was exposed to jazz, mariachi, classical and R&B.

My father loved Mariachi music, so I was listening subliminally and hearing harmonies. People say, “Geez, ‘Life of Illusion’ is kind of a Latino bass line,” and when you put trumpets on there it’s a Mariachi style. That’s probably from the influence of my father’s love for Mexican music. At a very young age, I was exposed to jazz, mariachi, classical and R&B.

It started as a bass lick, just like “Happy Ways” from the Smoker You Drink record, and was recorded at the same session. Joe was very generous about saying, “Okay, you guys write some tunes and if it works we’ll get them on the record.” After Barnstorm had broken up, Joe called me years later and said, “I have this track that you wrote. I wrote lyrics to it, and I call it “A Life of Illusion.” I want you to come to Santa Barbara and bring your trumpet.” I thought, “Wow, these are heavy lyrics.” We had some lyrics from Bernie Taupin’s end and someone else too, but Joe had these lyrics. It became a hit in 1981 and was revived by the movie 40 Year Old Virgin many years later. That was played on a guitarron and a fretless P bass. It’s a really interesting combination.

3. “In the Way” – From Stephen Stills’ Stills (1974)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

Stephen had another bassist on other tracks… maybe Lee Sklar, because Russ Kunkel was on drums. Stephen said, “I can’t get the bass part to this one song.” We were in Miami, and I said, “Let me try it.” So I used his bass, a ’61 Precision. I remember Paul Anka was there. It was a morning session in Criteria, and Stephen loved the part. It was latino, but at the same time, the sound and the touch worked.

Stephen had another bassist on other tracks… maybe Lee Sklar, because Russ Kunkel was on drums. Stephen said, “I can’t get the bass part to this one song.” We were in Miami, and I said, “Let me try it.” So I used his bass, a ’61 Precision. I remember Paul Anka was there. It was a morning session in Criteria, and Stephen loved the part. It was latino, but at the same time, the sound and the touch worked.

All my overdubbing, I learned, I would do in the control room. Then I could really listen to them through the speakers and not through headphones. Anytime I overdubbed, even on “Rock of the Westies,” I learned with Stephen. Standing in the control room and playing along was like I was playing live with the band. I just locked into the instruments as well as with the vocals. It was a new reference point in what makes me different. I’ve been listening so closely to all my work especially with all the interviews I’ve been doing lately. I was conversing with instruments, so that’s really what makes a difference for me. In “In The Way,” it was less playing a “bass part” than playing a part of the whole.

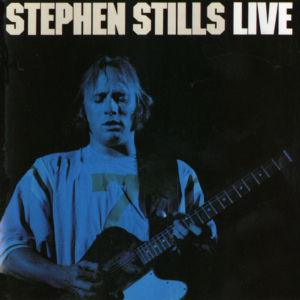

4. “Black Queen” – From Stephen Stills’ Stephen Stills Live (1975)

(Youtube)

When I worked with Stephen then, I was playing his fretted ’61 bass. I think the summer tour I did with him, he allowed me to use my fretless, but at the Auditorium Theatre, that’s a ’61 Precision bass. It was an incredible group. Donny Dacus on guitar, Russ Kunkel on drums, Jerry Aiello on B3, Joe Lala on percussion. It was killer and a great performance. It’s a monster track. I didn’t like the way they mixed the vinyl when I first heard it, but when I listened to it again, I was blown away. I revisit a lot of stuff that I was very critical of, and now it’s a total experience. I think I was playing an Ampeg SVT.

When I worked with Stephen then, I was playing his fretted ’61 bass. I think the summer tour I did with him, he allowed me to use my fretless, but at the Auditorium Theatre, that’s a ’61 Precision bass. It was an incredible group. Donny Dacus on guitar, Russ Kunkel on drums, Jerry Aiello on B3, Joe Lala on percussion. It was killer and a great performance. It’s a monster track. I didn’t like the way they mixed the vinyl when I first heard it, but when I listened to it again, I was blown away. I revisit a lot of stuff that I was very critical of, and now it’s a total experience. I think I was playing an Ampeg SVT.

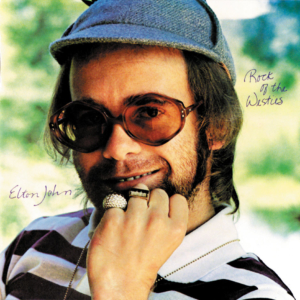

5. “Yell Help / Wednesday Night / Ugly” – From Elton John’s Rock of the Westies (1975)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

On Rock of the Westies, I came with a fretless bass. That’s what I’d been playing, and that’s what I felt I’d been hired for. We were cutting live, so after a few takes, I came out of the studio and [producer] Gus Dudgeon called me into the control room like a principal from school. He said, “I just couldn’t get a sound for your fretless. You need to find another bass.” I couldn’t believe it because I knew how good it sounded. The fretless just had this wall of sound, but he just wasn’t used to it. He was used to overdubbing. He took ten days to do drum sounds, so he had a totally different approach from what I was used to. Long story short, Jim Guercio (who owned Caribou), let me borrow three basses: a Gibson Firebird, a Fender, and a Hofner bass that McCartney had given him after mixing Ram. The action was ridiculous – it must have been close to an inch high. And I’ll be damned, that was the bass they wanted to use. I hated it. Everything but three tracks were all that Hofner bass. I think that’s how he and Dee [Murray] had done all the previous bass stuff. For the next record, I went out and bought the most expensive Alembic bass I could, so Blue Moves is completely that Alembic.

On Rock of the Westies, I came with a fretless bass. That’s what I’d been playing, and that’s what I felt I’d been hired for. We were cutting live, so after a few takes, I came out of the studio and [producer] Gus Dudgeon called me into the control room like a principal from school. He said, “I just couldn’t get a sound for your fretless. You need to find another bass.” I couldn’t believe it because I knew how good it sounded. The fretless just had this wall of sound, but he just wasn’t used to it. He was used to overdubbing. He took ten days to do drum sounds, so he had a totally different approach from what I was used to. Long story short, Jim Guercio (who owned Caribou), let me borrow three basses: a Gibson Firebird, a Fender, and a Hofner bass that McCartney had given him after mixing Ram. The action was ridiculous – it must have been close to an inch high. And I’ll be damned, that was the bass they wanted to use. I hated it. Everything but three tracks were all that Hofner bass. I think that’s how he and Dee [Murray] had done all the previous bass stuff. For the next record, I went out and bought the most expensive Alembic bass I could, so Blue Moves is completely that Alembic.

Elton let me do whatever I wanted to do. When I tracked with Elton, I’d stand next to his piano and watch his left hand. Once I had learned the song, I did what I felt needed to be done. “Yell Help” was an overdub bass part on the Hofner based off of what I did live on the fretless. I think it might have been a blessing in disguise because when I got into the studio, I realized I might have approached it a little bit differently from what I had played. My approach was once I got into the control room I turned it into more of a New Orleans tuba part. Again, you have to remember that I’m a brass player, too. Some of my playing is very influenced by my work as a brass player. I didn’t play baritone or tuba, but I understood that part of it.

That song really burns at the end. It gets down, man. A lot of people rediscover that record. The basic tracks of the whole medley were cut live, so I was flabbergasted when I had to redo it.

6. “Chameleon” – From Elton John’s Blue Moves (1976)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

I feel this might be one of my best performances in terms of playing all the styles I was influenced by, whether it was Jamerson or other people I was listening to. It all came together on that song. I heard it right after it was composed. It was before Rock of the Westies, but Elton didn’t use it until Blue Moves. We cut that in Toronto at Gordon Lightfoot’s studio, Eastern Sound. It was cut live – we just played it through. On that record, [guitarist Caleb Quaye] had really rebelled against Gus and said, “Less overdubbing, more live.” All of us together had enough clout to make Gus follow suit with that.

I feel this might be one of my best performances in terms of playing all the styles I was influenced by, whether it was Jamerson or other people I was listening to. It all came together on that song. I heard it right after it was composed. It was before Rock of the Westies, but Elton didn’t use it until Blue Moves. We cut that in Toronto at Gordon Lightfoot’s studio, Eastern Sound. It was cut live – we just played it through. On that record, [guitarist Caleb Quaye] had really rebelled against Gus and said, “Less overdubbing, more live.” All of us together had enough clout to make Gus follow suit with that.

[Kenny’s note: “Chameleon” is going to be featured as a transcription in Bass Player Magazine.]

7. “Sorry Seems to be The Hardest Word” – From Elton John’s Blue Moves (1976)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

This again is the Alembic bass and me standing [next to Elton] with just the two of us, and maybe [drummer Roger Pope] played a little time. There are several tracks on that album that are just Elton and myself and Roger.

This again is the Alembic bass and me standing [next to Elton] with just the two of us, and maybe [drummer Roger Pope] played a little time. There are several tracks on that album that are just Elton and myself and Roger.

As I stood next to him to learn the song, then he went away from the root I made sure I knew those parts so I could do exactly what he was doing on that part. There’s little overdubbing on the whole album. I can remember this track so well. He sang a scratch vocal, and I played right along with his left hand with my syncopation parts here and there. He never told me what to play. He never looked up. He just let me be myself, and I have great respect for my time with such a brilliant artist who wasn’t some dictator. He knew what he wanted from the people he had, and he let me play. Once I understood the composition, I did what I did. James Newton Howard did these wonderful string arrangements that bounce off my bass part.

It’s one of my favorite bass performances ever. I love the song so much, and the groove was so hip. Roger Pope was one of the greatest drummers ever. His time was impeccable, and he was funky for a British guy.

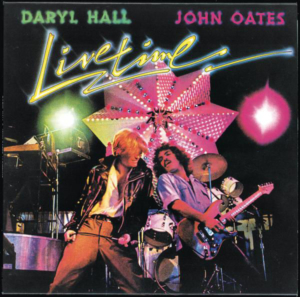

8. “Sara Smile” – From Hall and Oates’s Livetime (1978)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

That’s a fretless Oasis bass on that. We did two nights there, I think. I remember the stress of knowing we were recording. I don’t remember playing so much but listening back I remember how electric it was. It was funky. We did a little reggae kind of breakdown in there. There were 10,000 people there, and the audience was really into it. Daryl is one of the best singers I ever worked with.

That’s a fretless Oasis bass on that. We did two nights there, I think. I remember the stress of knowing we were recording. I don’t remember playing so much but listening back I remember how electric it was. It was funky. We did a little reggae kind of breakdown in there. There were 10,000 people there, and the audience was really into it. Daryl is one of the best singers I ever worked with.

I never played with any pedals. When the bass drives in the song it’s just from me digging in. I never used any pedals. They had me direct. I can’t remember what amp I was playing back then, but we had such an incredible live system that it didn’t matter what amp I had. I got a reputation for playing stadium bass. I could really hear the stadium itself and hear that low frequency.

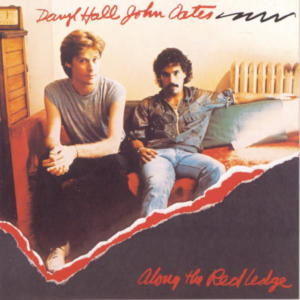

9. “I Don’t Want to Lose You” – From Hall and Oates’s Along the Red Ledge (1978)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

When I was done with the Alembic, we had done the Livetime record and I switched to the Oasis fretless. The scale was different from the P-bass and it was a little hard to keep in tune. John and I were cruising around the Valley and found it in a music store. It was a ’61 Jazz.

When I was done with the Alembic, we had done the Livetime record and I switched to the Oasis fretless. The scale was different from the P-bass and it was a little hard to keep in tune. John and I were cruising around the Valley and found it in a music store. It was a ’61 Jazz.

I overdubbed some of those top runs. At that point, David Foster had worked a lot with David Hungate. He suggested some parts for me other than the basic track. I wasn’t one of those slap and thumb guys, but Hungate was back in the day, so Foster said I should try it. I will definitely give him credit for that.

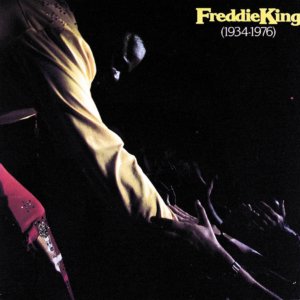

10. “Sweet Home Chicago” – From Freddie King’s Freddie King (1934-1976) (1977)

(iTunes | Amazon MP3)

Before the Hall and Oates record, I lucked out while I was still with RSO and overdubbed bass for Freddie King on the song “Sweet Home Chicago.” He was already deceased. The producer, Bill Oates, said, “Listen, I’ve got a track here. Clapton is on it and a few other people, but there’s no bass. It was done in England. Can you come over and put a bass line on it?” So there I am laying down bass for the deceased Freddie King on what I think is one of the best versions of “Sweet Home Chicago.” I met Freddie when he was alive. He was playing in Boulder and brought his bus up to Caribou to hang out with Stephen. To actually play on a record for one of his signature songs was really a high point for me. I remember cutting it and hearing Freddie’s voice on the track. It was a real treat for me.

Before the Hall and Oates record, I lucked out while I was still with RSO and overdubbed bass for Freddie King on the song “Sweet Home Chicago.” He was already deceased. The producer, Bill Oates, said, “Listen, I’ve got a track here. Clapton is on it and a few other people, but there’s no bass. It was done in England. Can you come over and put a bass line on it?” So there I am laying down bass for the deceased Freddie King on what I think is one of the best versions of “Sweet Home Chicago.” I met Freddie when he was alive. He was playing in Boulder and brought his bus up to Caribou to hang out with Stephen. To actually play on a record for one of his signature songs was really a high point for me. I remember cutting it and hearing Freddie’s voice on the track. It was a real treat for me.

Kenny is a national treasure. His playing on ROTW was transformative for me as a 9-year old hearing this record. It’s really cool to hear these other records he’s played on. What a great career and hopefully lots more to come.