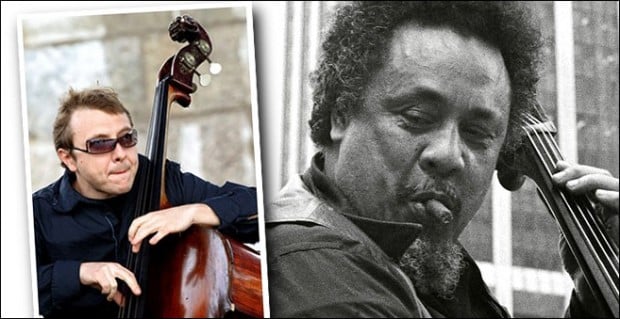

Carrying on the Mingus Dynasty: An Interview with Boris Kozlov

It’s not easy to fill the shoes of a legend, and Charles Mingus has some huge shoes to fill. The iconic jazz bassist and composer left behind a body of work so massive, so complex, and so uniquely his own that it takes an equally rare musician to convey its spirit. Mingus’ music lives on through the Mingus Big Band, the Mingus Dynasty and the Mingus Orchestra. All of the bands are overseen by bassist Boris Kozlov, who also acts as arranger and musical director for the groups.

Kozlov was born in Moscow during the Soviet regime and began his studies on piano. He eventually found his true calling on bass and won the Gnesin Music Academy Competition to enter college at just 15, where he studied electric bass guitar.

After serving his mandatory two years in the Soviet army, he was hired by the State owned “Melodia” Studio Ensemble. He won the first USSR Competition of Jazz soloists in 1991, which compelled him to expand his career to the jazz scene in New York City. A humble beginning in the city strengthened his resolve to push himself musically, which led to work with heavyweights like Benny Golson, Eddie Palmieri, Bob Berg, Jeff “Tain” Watts, and many more. He also leads his own bands and released his solo debut, Double Standard, in 2010.

Among his many gigs, he regularly plays with the Mingus bands at the Jazz Standard in Manhattan every Monday night. The big band’s album Live at Jazz Standard won a Grammy in 2011.

Among his many gigs, he regularly plays with the Mingus bands at the Jazz Standard in Manhattan every Monday night. The big band’s album Live at Jazz Standard won a Grammy in 2011.

We reached Boris to get deeper into his background, his insight into Charles Mingus, and advice for up and coming bassists.

Before you came to the U.S., you were a top jazz musician in the Soviet Union. Was was the Soviet jazz scene like?

In the ’80s, when I was just starting to get into the music, it was sort of limited. The prehistory of that is that in the ’70s, the Soviet government got scared of rock and roll, so they established the Youthful Harmonic Jazz Band. Naturally for all the young people studying jazz and being in college, those were the pinnacle goals: to eventually make it into one of the three big bands in the country where people were on salary and on tour.

There were [also] ensembles just put together from time to time maybe by various people, and one of those ensembles I became part of when I was in my third year. The piano teacher, who now has the title of something like “People’s Artist,” he was a pretty popular pianist and he was teaching in the college. It wasn’t a steady thing, but he would have two or three gigs a month out of town, so I was flying around with him. So the scene was not sprawling but it was more or less steady. There were some kind of lighthouses that you could move towards something.

After I got back from the army in 1989, those bands were still in place, but also tons of other avenues started opening up. That was kind of a crazy time because we didn’t know exactly what was going to happen but we knew something was moving. Within the framework of two years, I actually made three trips to the U.S. with different bands because the whole exchange thing opened up. So when you say the Soviet jazz scene, there’s a certain tradition. It started in a large part in the ’60s with people like my teacher, Anatole. His favorite was Ray Brown and Paul Chambers. He would use a tape machine to record Radio Liberty or Voice of America, and they would have programs twice a week. He would record the shows and later transcribe them. I remember he would give me a book of pencil-written quarter note lines by Paul Chambers, which he transcribed by himself. He was classically trained, but he was self-taught as far as jazz goes, and that was pretty much the generation of all of our teachers. They basically created the Soviet scene by scratch, plus they went through hard times for it, so they’re like a generation of heroes in a certain sense.

Do you mean they had hard times like jazz musicians in the U.S.?

Not really, because the kind of trouble you have here is absence of work, or you being a drug addict, or the IRS is on your ass, right? We’re talking about being persecuted by various institutions, be it expelled from school or be it chased by the KGB just for playing music and trying to establish contacts with foreign musicians. There are different levels of hardships.

So it was a big change for you when you came to New York.

Yes, and a very needed change. They put me as number one young jazz musician in the polls that year, and I could pretty much play with anybody I wanted to. Then I came to New York and I had to start out by playing in the subway. That kind of puts things in perspective.

Yes, and a very needed change. They put me as number one young jazz musician in the polls that year, and I could pretty much play with anybody I wanted to. Then I came to New York and I had to start out by playing in the subway. That kind of puts things in perspective.

I played in the subway, in retrospect, not only because I didn’t know anybody, but because I didn’t exactly have the skills needed to be hired where I wanted to be hired. With all that, I did have a steady gig in my second gig of coming here. Twice a weekend that steady gig involved the Hassan Williams band with two interchanging drummers: Mike Clark and Greg Bendy. So those were the first two drummers I got to play with and right away I knew that’s why I came here. Again, it pains me to acknowledge that there are less opportunities for young people now than for myself – a barely English-speaking foreigner – in the nineties. There were more opportunities for me to rub elbows over an extended period of time with some giants of jazz.

The jazz scene has always been cutthroat, but there were always these opportunities that you could really strive for. Now, you can still strive for a certain gig, but that gig will only happen once in two months. I’m talking about even opportunities before going on the road, I mean playing here in town. I remember the phone would ring and I would still have to play in the subway just to make my rent.

There would be the same guy calling me with the same group. Richard Clemons would play piano, Greg Bendy, and Hasan Williams. He would call me and say, “Hey man, we have a hit on Wednesday that pays fifty cents. You cool?” I didn’t even know enough English to distinguish all the words, and I’d ask myself, “What is fifty cents? What is cool?” Now there are these brilliant people here at Manhattan School of Music, and they don’t have any calls because there are no steady bands anymore. That’s one of the blessings of the Mingus band. Fifteen years and it’s more or less a steady group of musicians. Even with playing the same music sometimes I still feel there’s a blessing of a steady gig; not for the sake of the gig itself, but for the lineage.

How did you land the Mingus gig?

Tommy Campbell, the drummer. Tommy was on this record Sunny Days, Starry Nights with Sonny Rollins. It happened to be licensed to Melodia, which was the government label in the Soviet Union. That happened to be one of the two records I had when I was in the army for two years. I really had a chance to learn all the musicians on that record, so it’s only natural that in my first month in New York in this club, I went to see Tommy Campbell there because he was playing with his band. I got to know him and formed a street band with one of his students. We had this one big eight hour gig and Tommy came out to play with us, and he was already playing with the Mingus band at that point. Naturally, when the time came that [the Mingus band] needed a bassist on short notice, Tommy recommended me, and I’m forever grateful to him. He recommended me and then he left for Japan two weeks later to live there for twelve years.

Tommy Campbell, the drummer. Tommy was on this record Sunny Days, Starry Nights with Sonny Rollins. It happened to be licensed to Melodia, which was the government label in the Soviet Union. That happened to be one of the two records I had when I was in the army for two years. I really had a chance to learn all the musicians on that record, so it’s only natural that in my first month in New York in this club, I went to see Tommy Campbell there because he was playing with his band. I got to know him and formed a street band with one of his students. We had this one big eight hour gig and Tommy came out to play with us, and he was already playing with the Mingus band at that point. Naturally, when the time came that [the Mingus band] needed a bassist on short notice, Tommy recommended me, and I’m forever grateful to him. He recommended me and then he left for Japan two weeks later to live there for twelve years.

Eventually that street band disbanded, but honestly it’s something that I miss to this day because there’s a certain feeling, a certain adrenaline to it. It’s like you have to be on all the time or you won’t make a dime. Because the New York crowd won’t stop for nothing.

I know you used Mingus’ Roth bass on your solo album, Double Standard. What’s the state of the bass now?

It was sitting in my house for years and I used it on gigs, then it was time for appraisal because it’s part of Mingus’ estate. So Sue Mingus did an appraisal on the bass and it needed a lot of work. They did the work and the insurance paid for it. I walk everywhere here, so I don’t want to bump that bass around. So it sits at Sue’s place and any time I need it I can come over and get it. And for maybe larger events like the high school competition in February that she does, I play that bass that month and of course we do clinics where the kids get to come and play the bass, especially the winners. I always encourage to play the bass, to feel it… it’s a lot of fun. So the bass is completely fixed and it sits in front of my cases over at Sue’s apartment. That’s basically it. It’s more comfortable for me that way and for her too, though she says the bass has to be played.

When you play it, does it feel like the holy grail to you or does it feel like another bass?

At first, there was a sense of holiness about it. I did feel the spirit. Also in reality, at that time it was probably the best bass I ever played, so there was a curious joy about it. The dynamic you know… you just push it more and it really opens up. It’s kind of narrow and a shorter scale. Slightly shorter scale, but not by much – maybe 40 1/2 inches or something. So the feeling was a combination of my knees shaking from the fact that I’m playing Mingus’ bass and just being happy that it was way better than my hybrid Czech.

At first, there was a sense of holiness about it. I did feel the spirit. Also in reality, at that time it was probably the best bass I ever played, so there was a curious joy about it. The dynamic you know… you just push it more and it really opens up. It’s kind of narrow and a shorter scale. Slightly shorter scale, but not by much – maybe 40 1/2 inches or something. So the feeling was a combination of my knees shaking from the fact that I’m playing Mingus’ bass and just being happy that it was way better than my hybrid Czech.

The history of the bass was that some guys didn’t like it because they felt they had better basses in their stable. Some of the bassist’s before me, like John Benitez loved that bass and he played it for a second. Michael Formanek got in a fist fight the first night he had the bass, so he attributed it to the spirit of the bass and put it back. So I guess everyone has their own relationship with it, but I loved it. We would take it on the road a lot and I would just record with it in hotels and I would just put a Neumann mic in front of it.

If we stayed somewhere for more than three days, I would search around for a quieter hotel room facing the inner yard or something. One time in London a friend of mine, Mike Sim, who just mixed the album we’re about to put out, which is basically electronic versions of Mingus’ music, completely rearranged and reconstructed by yours truly. [It has] two tenors going through synth, two drum sets and electric bass in the middle.

When is that coming out?

As soon as we move it. If I don’t have a record label by next month, we’re just going to put it out. So that guy, he played baritone at the time in the Mingus band. He wound up having jaw issues and trouble playing so he became an engineer. He did me a big favor by just once finding a good mic positioning for me. Every time I would come to the hotel room, I would use the same tripod, spacing, and so on. It’s amazing to me how little the acoustic space itself was contributing to the recording.

Since you’ve had the Mingus gig for so long, what sort of insight have you picked up about the man and his music?

His music is very reflective. When you just play the music and get really familiar with it, you have a big scope into Mingus’ persona already. His stuff rarely stays in one place, and he also had all these aspirations to write like a classical composer and create larger forms. He also hated when people would play and groove in one place; that wasn’t his thing. He wanted to challenge the soloist constantly, which is very close to my heart. Being a bassist, my favorite music is where there is an interplay. Even with the constant motion of drums and bass, there’s still a chance for interplay, but historically my favorite stuff is when the interplay happens. Mingus was sometimes by force inducing that type of thing.

[Mingus] was a whole bunch of guys, and you never know which one you would encounter. The usual stuff you hear like he was rough and would throw the bass… Well he did throw the plywood bass at the audience once, but he knew what kind of bass he was throwing. That kind of stuff is only one small side to him. My contemporary Peter Brainen, a tenor player, was a ten year old clarinet playing boy and his father was really into [Mingus’] music. His father brought him to a Mingus gig and Mingus sat him down at the bar, talked to him and bought him a Coke. So, he had many sides to him. He had emotions swiping through him like a hurricane. I’ve heard stories about where he would get enraged about something and fire his whole band, almost on stage. Then the next day he would actually cry and apologize and be on his knees, not only saying he was sorry that he fired them but also that he was sorry that he treated guys that way.

In all those stories and in his music, and in Sue’s book as well – which is one of the most honest books about him out there – what comes through to me is that he was always honest. He never had any funny business about anything. Guys who worked with him said there was never any logistical or money problems. Everything was really clear. Yes – you might be hit with the hammer one night, but you’d be apologized to the next day.

Of course, he was very demanding of people. He would try to elevate or bring out sides of people that they didn’t expect they had. Sometimes pushing a little bit [helps a lot], which I try to keep in my mind as bassist in the Mingus band. Just pushing a little extra – and I’m not talking about time or tempo – just pushing as far as concept. You’re running the scare of throwing the whole band into chaos sometimes, that’s the danger, but you always have to push it a little bit because that’s the beauty. It’s the part that makes the music ring and make a real vibration.

What advice would you have for bass players coming up now?

I don’t know the remedies for the modern day blues, but I can only speak for what I was searching for and go to. The main advice would just be to keep your ears open. I came to New York with a preset knowledge of what I wanted to do. Eventually I had to alter my desires and my time, my approaches and stuff and it got me into totally different stuff. I never knew I would be playing Caribbean music. It was never even on my wish list. So, keep an open mind and play a much as you possibly can because again, it’s quite unlikely that you’ll land a major gig with an old-timer for the whole aural tradition that jazz is. It’s harder and harder, so just keep playing as much as you can, and try to enjoy everything that you do.

Looking back now, I used to play four hours in the Subway in the morning and sleep a little in the day, then play four hours in the evening. Then I would go to a little fifty dollar gig, and after that I would hit every jam session that was in town. I look back and think some of that was pretty hellish, having to take a Subway back to Brooklyn with two basses at three o’clock in the morning when the trains barely run, only to sleep for an hour and a half to come out again to Columbus Circle station to play. So, try to enjoy all of it. You have to like what you do.

I’ll never forget Leroy Vinnegar told me back in the ’90s: “If you don’t mind being poor and you stay in New York long enough, you might have chance at becoming a master.”

I remember that quote every day.

I was at Boris` gig in Moscow, Russia, yesterday.

He played 6-string electric bass in the group with the singer and drummer, and it was completely new experienece for me to hear how just one bass guitar holds all the harmonic and rhytmic structure of the ensemble. They really didn`t need a pianist, Boris played bass lines and some chords/melodic lines on top simultaneously, and it was so musical and tasty.

Again, I`ve heard a lot of jazz, but that was something unusual.

Do not hesitate to listen Boris live, you won`t regret for sure.