Bass Dynasty: An Interview with James Jamerson, Jr.

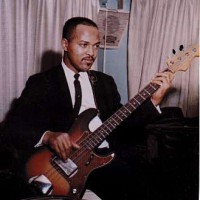

It’s not easy to fill the shoes of a man regarded as one of the most influential pioneers of the electric bass, but it’s something that comes naturally to James Jamerson, Jr. After all, his father – who subsequently changed the face of popular music – was the one who taught him to play. He practically grew up in the legendary Motown Studio A, where Jamerson, Sr. recorded more hits with more musicians than many can even imagine.

It’s not easy to fill the shoes of a man regarded as one of the most influential pioneers of the electric bass, but it’s something that comes naturally to James Jamerson, Jr. After all, his father – who subsequently changed the face of popular music – was the one who taught him to play. He practically grew up in the legendary Motown Studio A, where Jamerson, Sr. recorded more hits with more musicians than many can even imagine.

James Jamerson, Jr. got into the business alongside his father, but later branched out to play with over 200 artists ranging from the Temptations to Bob Dylan as well as work on several soundtracks. His latest solo effort, I’ll Be There, is a tribute to Michael Jackson.

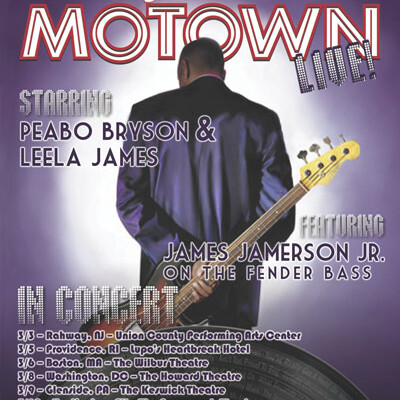

The bassist will be standing in his father’s place on an exciting new tour called “Standing in the Shadows of Motown LIVE!”, which marks the tenth anniversary of the Motown documentary of the same name. The tour will feature over two dozen Motown hits focusing on the music of James Jamerson, and the 11-piece band is filled out with veteran sidemen as well as the film’s producer and creator Allan Slutsky.

We reached out to Jamerson, Jr. to get the low down on the new tour, his career, his father’s gear, and what it takes to get the Jamerson sound.

Congratulations on the new tour. It looks like it’s going to be amazing.

Yeah, it’s gonna be cool. Actually this tour could go on forever. I mean, Motown went on for over a decade when dad was around. There were so many hits [in that era], it’s kind of hard to pick just one.

I read you’re doing two dozen, but there are tons more to pick from.

From the ’60s to the ’70s, up to the middle part of the ’80s. I started recording with them around the mid-70s. They would get confused between me and my father, saying, “Wait a minute, this has to be a misprint.” But that was those that didn’t know. Smokey [Robinson], Berry [Gordy] and the rest of the Gordys, and Marvin [Gaye] and those kind of guys, they knew, but some of the office people didn’t know. They’d ask my dad, “Is this right? Your son plays? Can he really play?” Dad would say, “Oh yeah, he can play.”

At least that’s what I’ve been told. I guess I can play after all these years.

What was your first gig with Motown?

I was in the studio in the Snakepit one day and my dad left the room. There was a song that was basically kind of easy. I think I was around 14 years old. It was a song called “Flower Girl” by Smokey Robinson. Since [Dad] had left the room, Earl VanDyke and Robert White egged me on to pick up the bass. Normally I wouldn’t do it, but I figured I was comfortable enough because I started learning how to play the bass at night. So that was the first thing.

Then after that when we moved out to California when I was 17 – going on 18 – I got a gig with the Temptations. Then I started working with the company doing some demos and stuff, and then the demos became the tracks. I did a road stint for maybe two years between ’75 and ’76, but I was full fledged around ’77. After that I started recording with different artists, from Tata Vega to Marvin.

I went from doing Motown stuff to other acts from Rock to Bach: Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, the Jacksons, Luciano Pavarotti…

What did you do with Pavarotti?

Well, this was during the disco era. He wanted to sing “Pagliacci Disco Style.” So yeah, that was an interesting gig. [laughs] He said, “I’m taking all you guys out to dinner. I wish I could take you all on the road but it would be just for this one song.” He was a nice guy.

That sounds like a trip.

Yeah. That’s why I say I’ve worked from Rock to Bach. I feel blessed that I’ve been able to work with the best musicians, the best producers, and the best writers. I’ve been around the best period, but some of it when I was growing up I didn’t know I was around history-making people. I didn’t even know about my dad; I thought bass was played like that all the time. It was like a given. Then I came to find out that dad was changing the whole course of music.

When did you realize that?

I didn’t realize that until maybe around 17 or 18. I didn’t really get it. I would just say I’m playing bass like him, and people would say, “No, you’ve got to understand what your father has done. Your father is the pioneer for electric bass. He’s turned the whole business upside down.” I didn’t realize that. He was just my dad. That’s just like someone that goes to work at a factory. That’s his job and that’s what he does. I liked what he was doing because during the Christmas time, I got interested in music. I didn’t know if I was going to be a scientist or a musician. It turned out musician. So there it was: same name, same instrument. [laughs] I know that he was happy before he left here because his son was making noise.

I didn’t realize that until maybe around 17 or 18. I didn’t really get it. I would just say I’m playing bass like him, and people would say, “No, you’ve got to understand what your father has done. Your father is the pioneer for electric bass. He’s turned the whole business upside down.” I didn’t realize that. He was just my dad. That’s just like someone that goes to work at a factory. That’s his job and that’s what he does. I liked what he was doing because during the Christmas time, I got interested in music. I didn’t know if I was going to be a scientist or a musician. It turned out musician. So there it was: same name, same instrument. [laughs] I know that he was happy before he left here because his son was making noise.

I had my own hit record too, in ’78. [The band] was called Chanson, which a French name that means “song.” That was me and David Williams. At that time, they didn’t really know how to classify it, because we were primarily supposed to be a disco act. We were fortunate enough to have a hit record and do the different TV shows.

What inspired the tour to come about?

Me and Allan [Slutsky] had been talking about this for a while, just saying “Hey, let’s put a tour together.” After the funksters started dying off, we said we really need to concentrate. Nobody really left. I said, “I’m alright, I can play like my father.” I have my own thing that you’ll hear my traits, but I can play like my father. That’s what I know; that’s in my blood. It comes easy to me. That’s the way I’ve played all my life. I didn’t change up until I think I was about 23 years old.

Me and Allan [Slutsky] had been talking about this for a while, just saying “Hey, let’s put a tour together.” After the funksters started dying off, we said we really need to concentrate. Nobody really left. I said, “I’m alright, I can play like my father.” I have my own thing that you’ll hear my traits, but I can play like my father. That’s what I know; that’s in my blood. It comes easy to me. That’s the way I’ve played all my life. I didn’t change up until I think I was about 23 years old.

Me and my father had a talk and I said, “You know, I’m kind of getting tired of everyone telling me to ‘play like your father.’” My father said, “You’ll never be me, and I’ll never be you. Just go on out there and kick ass.” That’s it.

So I just started saying, “If you want dad, you call him.” Everybody got used to me doing my thing, and I started getting the calls. I had a whole other thing, because I would slap.

And your dad never got into slap, right?

Oh no. My father would never get into that. He would say, “That’s your job. You do that. If they want that slap, I tell them to call you.”

You still must have felt a lot of pressure.

There was always pressure during that time.

We posted before about PBS trying to track down your father’s amp and that you didn’t think that they found it.

That’s not the amp. It’s not, because there’s three pictures – two that [PBS has], and one where my father is actually in the picture. The amp is to the side of him, and you can see there are no toggles on the right hand side. See, I grew up with that amp. That was the only amp that I had. I could either play the B-15 or his Kustom. When I was in the studio, I would have to take his amp. At that point, he wasn’t really working much.

Anyone could have gotten a stencil [to put on it]. It was a little too fresh. The bottom line is that it only had two pilot lights on the right hand side, not toggles. The toggles were on the left hand side. We didn’t find that picture until after the fact. You can see that it’s not the same amp that PBS called themselves having. He never owned no two different B-15s. He only had two amps: the B-15 and the Kustom. My father was not one of those that liked to have a bunch of equipment and stuff. Now me, that’s different.

So what do you think happened to the amp?

I have no idea. That’s just like what happened to the Funk Machine. All of that was stolen around the same time. First the amp was stolen, then a month or so afterwards, the bass was stolen. I would be one happy camper if those things came back.

So there have been no leads on the Funk Machine since then?

No, none at all. Somebody probably has it that we think is waiting for all of us to die off. It’s wrong, but you know how people are.

What gear are you using these days?

I have a custom bass by Le Fay. I also endorse Fodera, and naturally I have my P-bass. Those are my primary instruments right now. I endorse Hartke amps. I’ve got the LH1000 with a 4×12 and a 1×15.

How do you get the Jamerson sound, between you and your father?

It’s the instrument, but a lot of the sound is the person behind the instrument. It might mean that they come close to the sound, but once you get the sound, what are you going to do with it? I play with a lot of bottom like my father because that’s the way I was taught. A lot of guys play with a lot of high end to where it’s real trebly. It’s like, “Wait a minute, this is not guitar; this is bass!” There’s supposed to be bottom. It’s supposed to make you shake.

Great interview , very informative thanks for posting.

Well said! : “I play with a lot of bottom like my father because that’s the way I was taught. A lot of guys play with a lot of high end to where it’s real trebly. It’s like, “Wait a minute, this is not guitar; this is bass!” There’s supposed to be bottom. It’s supposed to make you shake.”

You’re absolutely right about that Josh. Too many guys playing bass with way too much raspy treble twang! It almost hurts my ears listening sometimes. I’m an old school “thumper” & proud of it. I’m 60 now & still use flat wounds 90% of the time, on 4 string basses only. Good luck with your playing, friend!