How to Read a Lead Sheet

Q: Can you explain how to read a lead sheet? Not the notes or rhythm (there’s plenty of information online about that) but how to know what the symbols mean and how to know where to go in the chart and when? Like repeats, codas, etc…

A: Yes! There seems to be real lack of easily accessible information about this online and I have a lot of students who can actually read a bit but still get confused trying to navigate the ‘road map’, as I call it.

I won’t bog you all down with latin and/or Italian names for things but I have drawn up a PDF of the more common things you might see on a chart. I’ll also provide three charts that you can read down yourself here as well as audio links. One chart is a scan of a handwritten ‘cheat sheet’ I made for myself years ago for a Stevie Wonder tune so you can see a shorthand example of what I might sketch out for a gig. Another is a pretty straightforward chart for a local band I play in that contains many of the road-map symbols I’ll talk about. The 3rd chart is pretty tricky. It’s one of my early tunes and I was (for some reason) determined to keep the chart to 2 pages and wound up creating a chart with multiple codas. It’s a weird road-map and not for the faint of heart (apologies to the guys at the session).

But first, let’s talk about how to go about reading a chart.

For the record, a chord chart is just a piece of music that reflects nothing but the form and chord changes. A lead sheet typically has the melody written along with chord symbols above it. Some lead sheets will also have bass parts written, some won’t. Some may have specific parts written only in certain sections. This is a part of why it’s important to map out the chart before you start to play. So you know what to expect before it happens in real time as you’re busy worrying about chord changes and locking with the band.

Whether it’s a lead sheet with a written line, lead sheet with melody and chords, or just a chord chart, the first thing I do is look at the ‘road map’. Just like reading a paper map on a road trip, I look at where I start and scan the chart from front to back, making a mental note of every twist and turn (or a physical note, actually using a highlighter on the chart or my Apple pencil on the iPad).

These numbers refer to the “Road Map Examples” (download the PDF).

- Some charts will have a pick-up bar at the top. This means that there is some melodic or rhythmic statement that happens before the tune really kicks off. Often, it’ll just be a few beats of melody (or, sometimes bass line). It will often not be written in any time signature but will just reflect the thing happening with however many beats it happens for. Often, the bandleader will tell you how they will count off the tune. If the pick-up bar has two beats of melody, they might say, “I’ll give you two up front”. They might also count 6, in order to make it all in 4/4 time (assuming the chart is in 4/4). In LA, it’s common for someone to announce how many beats up front they will count and they’ll say they are “for free”. As in, “I’ll give you 6 for free”, meaning that you might play the written pick-up in the example over beats 3 and 4 of their 2-bar count-in. Notice that the first thing written is the 8th rest. This means that you still won’t actually play on beat 3 but will rather wait until the ‘and of 3’ (as in 1-and-2-and-3-AND).

- Repeat symbols are just what they say. When you hit the end repeat “:||”, you jump back to the beginning repeat “||:” and play everything in between again. It’s just a way of saying do this part again. Sometimes it may have a little 4x next to the bar or might even say 4 times. This just tells you how many times to repeat those bars before moving on. In this example, you would play bars 1-4 twice.

- DS and DC. Without getting into the Italian names, if you see these written, do this: DC – go back to the very beginning of the chart. DS – go back to the ’S’ sign (example on PDF) (I just remember ’S’ for sign) If you see a DS in the chart, take the time to figure out where that ’S’ sign is in the chart. It’s not always obvious or easy to see, so it pays off to take a few seconds and make a mental note of where it is so you can jump quickly there while reading the chart.

- DC/DS “al finé” simply means that you go back to the appropriate spot (DC-beginning, DS-S sign) and then play the chart through again until you see finé. Finé is where you end the song

- DC/DS “al coda”. This means that you go back to the appropriate spot (DC-beginning, DS-S sign) and then when you see the bullseye graphic (example in PDF), you jump ahead to the next coda sign (bullseye looking thing). Sometimes a chart may just say “to coda”, so as not to clutter the chart with bullseye signs but you still just jump ahead in the form to the sign. Codas are common for the end of a song, where the form changes slightly to bring everything to a close. Since it only happens once, it’s a perfect spot for a coda. The key is making sure that you make note of where the first sign is on the chart, so you don’t miss it when you’re busy playing.

- Is an example of a DS al coda. If we start at bar 1, we would then take the DS at the end of bar 4, jumping back to bar 1. When we see the first coda symbol at bar 3, we jump to the second coda symbol at bare 5 and play on. So, following along with those bar numbers, we’d play 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8

- Multi-bar rests are just a way of saving space on the page. Instead of writing 8 bars of rest, we can just put an 8 over the whole rest in the bar. It’s usually made pretty big and obvious. When you see this, rest easy but don’t forget to count!

- 1st and 2nd endings. These are seen in the midst of some repeated sections. They simply mean that you should play the first ending the first time you play those bars but, the 2nd time, you should skip that 1st ending and play the 2nd ending. This example is just a 4 bar phrase repeated but, theoretically, there is something different about the very last bar (likely having to do with how it moves on to the next section. This is still an 8 bar phrase as the bar under the 1st ending only happens the first time through. The 2nd ending replaces it. You can also have the first ending with “1-5” written and the 2nd ending with “6” written. This tells you how many times to repeat that section before taking the next ending. In that example, you would repeat phrase 6 times, playing the first ending 5 times and only on the 6th time, playing the 2nd ending (which could be called a 6th ending here).

- These funny little ‘%’ looking symbols mean that you should repeat what happened before. How much of the before should you repeat? It depends on how many lines the ‘%’ has and how many bars it covers. There will generally be one line per bar you are to repeat, and it will almost always still take the space of however many bars you are repeating the phrase over. It’s a way of making the chart look cleaner if there a repeated line. Bass players see this a fair amount because we may have one line that is a 2 bar phrase but gets repeated for an entire 16 bar section. It’s just cleaner to write the phrase once and then have repeat bar symbols over the rest of the form. It’s important to keep track of where you are in the form and how many times you’ve repeated the phrase, mentally.

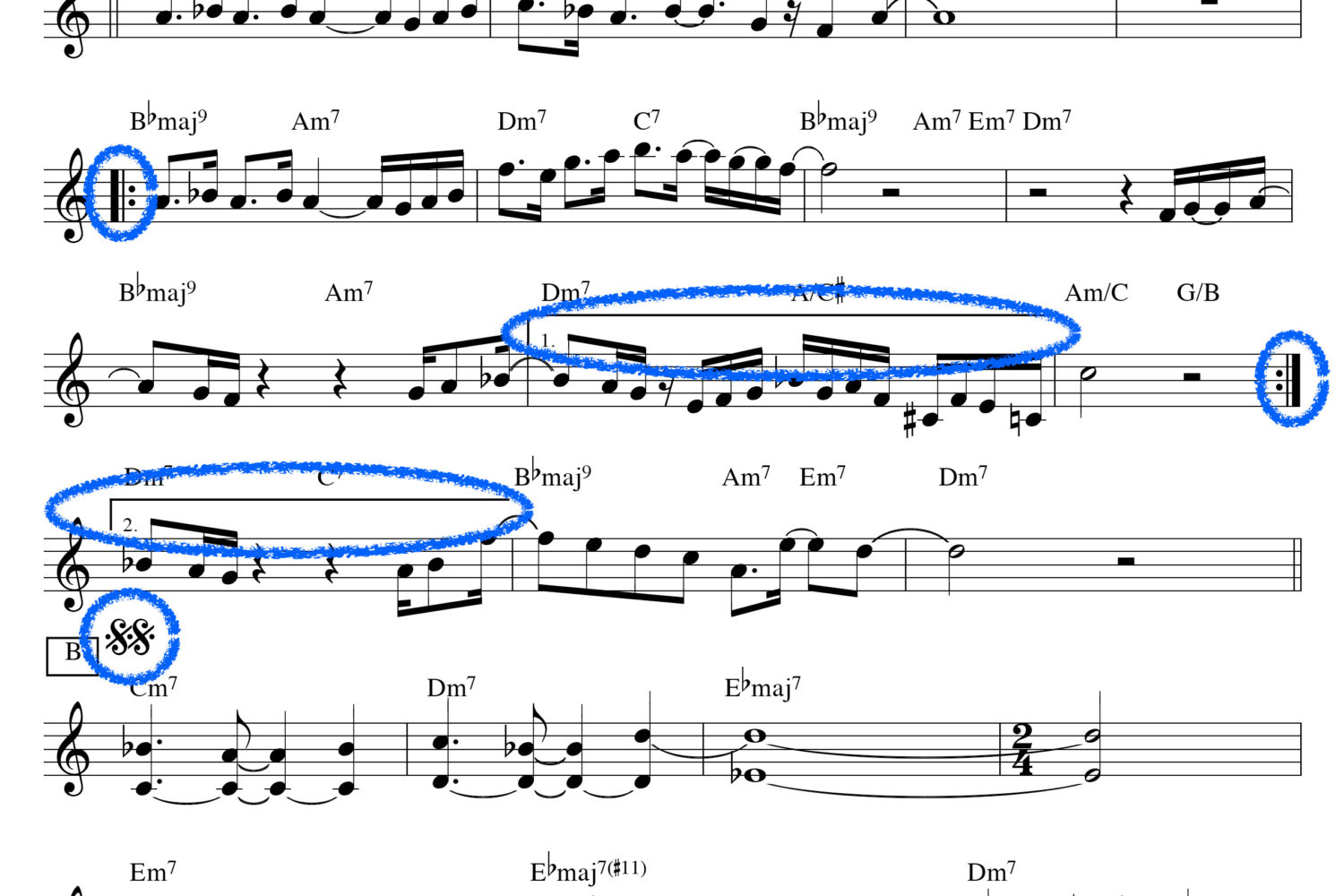

I hope that made some kind of sense or, at least, will as you use that as a reference and look at the following charts. I’ve included 2 versions of the charts here. One standard, as I look at it and one with all of the mentioned roadmap symbols circled in blue. If you look at that, you can visualize how I move through the chart with my eyes, starting from the beginning and then slowly working through the ‘road map’ before I play the tune.

Do Like You

- Download the chart (without marks)

- Download the chart (with marks)

As I mentioned, this was a quick cheat sheet I made years ago before a gig.

- Notice the 4 bar multi-rest at the top. This is a guitar and drum intro

- Repeat symbols on the A section

- Repeat symbols with 1st and 2nd endings on the B section

- And then my own shorthand note of the following sections after I’ve read the form down (another A section, B section twice).

* Synth 1-6 refers to the number of the sound on my Deep Impact pedal.

Baba:

- Download the chart (without marks)

- Download the chart (with marks)

This is a tune by my buddy Tarik Abouzied (whom some of you will know from the couple of times I’ve had asked write to a column).

This is from a recording we did a few years ago in Seattle.

- Notice the pick-up bar. He’ll usually count us in with a big 1-2-3 and then the horns play a rhythmic pattern over those first 3 beats starting on the 1. It’s pretty common for people not to count the last beat, especially if they have a lot of studio experience. In the studio, you want everything dead quiet in the seconds leading up to the first notes or hits of the tune, so tunes will often be counted in with the last beast or two felt internally.

- repeated section right off the bat. This is repeated until the melody starts, at which point we’ll be at the A section. It’s pretty common for an intro section to be open, with the melody cuing the beginning of the rest of the form.

- 4-bar long 1st ending on that A section

- 2-bar long do-it-again % symbols. That 2 bar phrase happens 4 times total

- Make note of the rhythms written in the last half of the B section. The chords change on those anticipations.

- repeats on the C section with another 1st and 2nd ending. Notice that the first ending says “open”. This means that you won’t take that next ending until it’s cued (by the soloist in this case).

- D section repeats in multiple spots. Open for bass solo with repeating sections to follow on cue. E section is the home stretch with just a 1st and 2nd ending before ending with those hits.

Kaluanui:

- Download the chart (without marks)

- Download the chart (with marks)

This is mine and it’s a pretty good example of how to confuse the band. I never fixed the chart because I don’t really ever play the tune. It was a one-time problem. If you can follow along, you are ready for anything anybody throws at you. Congratulations!

- Intro is repeated and usually just open until I cue the melody.

- A section. Make a note of that ’S’ sign so you know where to return to later

- last 7 bars of the A section repeat with a 1st and 2nd ending.

- TWO ‘SS’s?? WTH. Okay, so some charts have multiple codas because musicians are cruel and vindictive. It’s especially common on charts that might otherwise be 7 pages long. An ‘SS’ or “double DS” is just like a regular DS except that it happens only AFTER the first DS. Kind of like a note with a PS and then a PPS as an after-thought. You will take the first DS until you see the next DSS and then you will jump back to the double ‘SS’ symbol. And, yes, I have had charts with a triple DS. God help us all to end the song at the same time.

- C section. repeated but make note of the comment at the end. “no repeats on solos”. There’s also that dreaded DSS for later

- D section, nothing to see here but after this is your first DS. Back to the first symbol at the top of the A section!

- Play the for through, just like the first time until we get to the DSS at the end of the C section

- Back to the B section and through the rest of the form until the finé at the very end.

- This chart is way more convoluted that it should be but, hey… it makes for a good sight reading test, right?

So, to recap, when I am handed a new piece of music to play, here is what

I do the following:

- Scan for any written bass lines in the chart

- double check time signature (I don’t really bother with the key if it’s just a chord chart. I’ll just use the form and the changes but when there are written lines and I need to make note of the appropriate accidentals, you have to know what key you are in.

- Start walking the form through with my eyes. Making mental notes of repeated sections (sometimes repeated sections can be LONG. You may be repeating 2 pages worth of material, so you need to have an idea of where those beginning repeats are), DS’s, DC’s, codas, etc… This is also the perfect time to ask a quick question if you note sure of something. “Is the repeat for solos open? Who will cue out of the X section? etc…

The key to being a good sight-reader partially comes down to your ability to get the road map down quickly. Everything else comes down to experience, musical instincts (which come about through experience), and muscle memory (physical and mental).

Have a question for Damian Erskine? Send it to [email protected]. Check out Damian’s instructional books, Right Hand Drive and The Improviser’s Path.

This information is out there, but your commentary and examples made this invaluable to me. Thank you!