End to End: An Interview with Barre Phillips

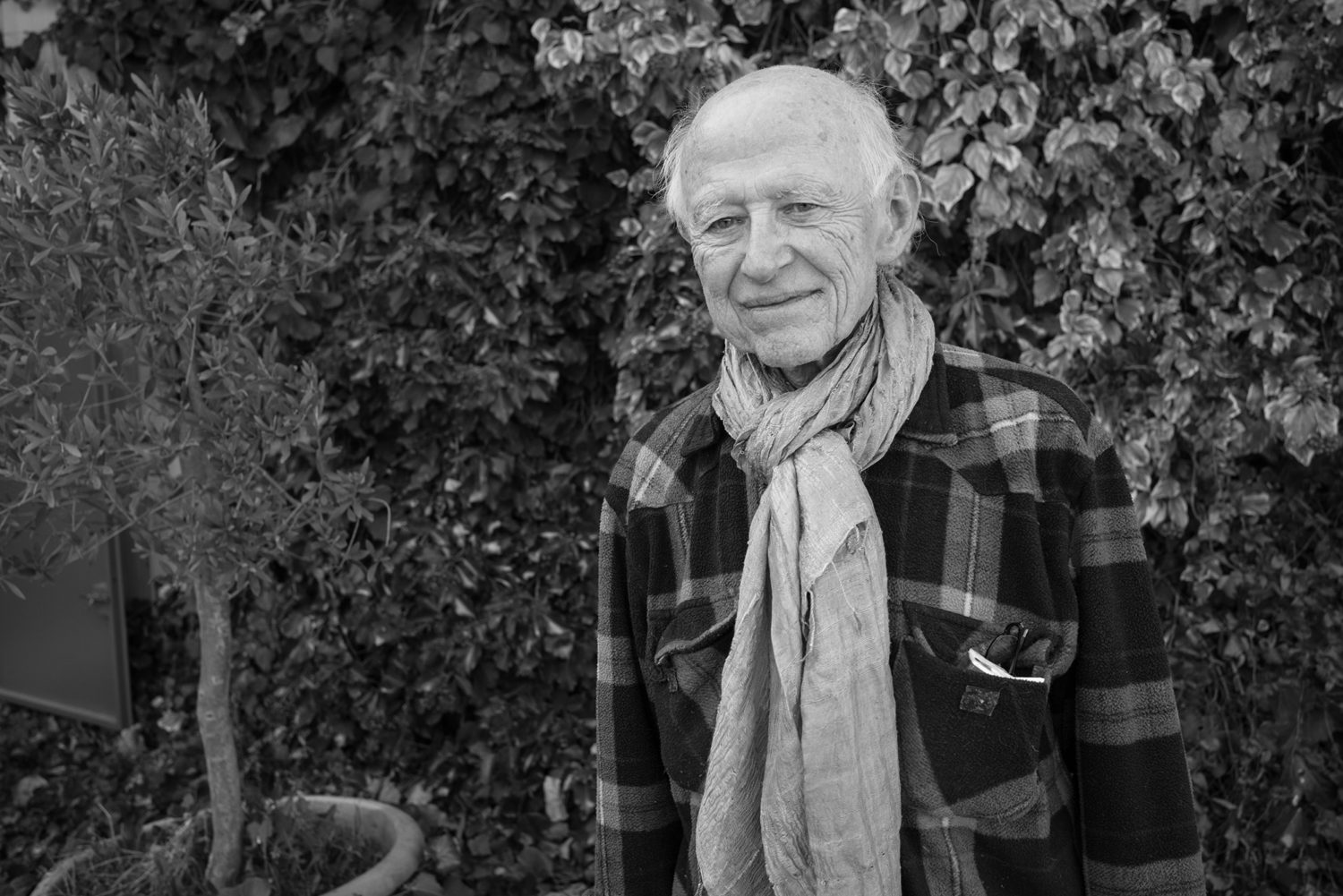

Double bassist Barre Phillips has been playing – and more importantly, exploring, the bass for nearly all of his 84 years. His work has made him a stalwart of the free improv community and his 1968 album Journal Violone is credited as the first ever solo bass record. 51 years later he’s just released what he says is his final solo album, End to End.

Phillips was born and raised in California and briefly studied with San Francisco Symphony assistant principal bassist S. Charles Siani when he was 25. He soon moved to New York and worked with jazz musicians like Eric Dolphy, Jimmy Giuffre, Archie Shepp, Attila Zoller, and more before realizing that being a traditional jazz bass player was not for him.

“I started to be a full-time player late – not until I was 25 years old. I wasn’t ambitious in that I wanted to be a great jazz player and make records. I just wanted to play,” he says. “In my era, if you wanted to be a pro jazz musician, you have to run yourself like a business to be successful. My work is more about improvised music, which is not about the product or show. It’s about the process of making music. I was philosophically, socially, and even politically interested to do that in public.”

Phillips found himself traveling to Europe for work and eventually stayed. He moved there in 1968 and has lived in southern France since 1972.

Although End to End will be his last solo recording, Phillips continues to work with other musicians and push himself to become a better bassist. Barre Phillips will be performing a special solo concert at the Zürcher Gallery in New York City on May 20th.

We caught up with him to find out about his background, the incredible story of the first solo bass record, and his views on improvisation.

When did you start on bass?

I started playing bass in California in junior high school with the symphony orchestra. I had an older brother who was playing Dixieland jazz, and when I came home with a bass he told me he needed a bass player. So in the same week, I started playing classical and jazz, completely untutored. I was self-taught for the first 15 years.

You were getting a lot of playing in. What pushed you towards this more experimental music?

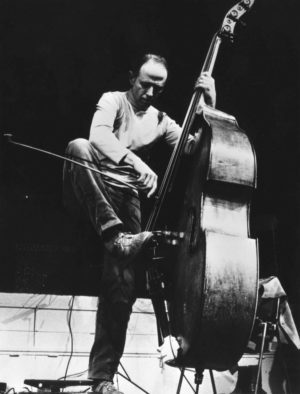

It’s circumstances and has a lot to do with my age. I was 26 or 27 when I left California and moved to New York. That’s when the free jazz scene was going on and there was a huge amount of contemporary music being written and performed at the same time. I was involved with the free jazz scene, but also with the contemporary music scene. That led me more and more to [discover] what you can play on the bass, which became a fascination for me.

It’s circumstances and has a lot to do with my age. I was 26 or 27 when I left California and moved to New York. That’s when the free jazz scene was going on and there was a huge amount of contemporary music being written and performed at the same time. I was involved with the free jazz scene, but also with the contemporary music scene. That led me more and more to [discover] what you can play on the bass, which became a fascination for me.

As I became more established in the business, I could spend more time not learning how to be a conventional bass player, but what was my take on the bass and what I was finding on the instrument. That seemed to be attracting people so I continued on.

People have pushed what kind of sounds you can get out the bass to the extremes. Do you think there’s still more to be explored on the bass?

I’m sure there are because that’s just how life is [laughs]. The standard of bass playing for someone who is 25 years old is completely different from 60 years ago when I was 25 in terms of what they can do already. It’s not only true with the bass; it’s true with all instruments, sports, and everything. There’s a general progression of things. More and more there are people looking for their own voice. It wasn’t so common 50 years ago in terms of an instrumentalist to be searching for their voice. We used to play with the models. Saxophone players in my era started off playing like Charlie Parker and Ben Webster and Coleman Hawkins, then they moved on to John Coltrane. There were models that you imitated to learn. It was the same for bass players, too. But I got off the standard route pretty early [laughs].

Who were some of those early models for you?

I was impressed from the early days with Pops Foster, and a bit later on I was impressed with Paul Chambers from the Miles Davis quintet. They were good, solid bass players with their own sound. Same as Ray Brown and how well he played rhythm and the sound of his bass.

I was impressed from the early days with Pops Foster, and a bit later on I was impressed with Paul Chambers from the Miles Davis quintet. They were good, solid bass players with their own sound. Same as Ray Brown and how well he played rhythm and the sound of his bass.

I was very interested in the very beginning with the bow. I played classical throughout all my student years, even a certain amount after I moved to New York. I was never really attracted to Slam Stewart, Major Holley, and Paul Chambers as a standard jazz bower. I never worked on that. I was more interested in Bert Turetsky with the bow than Paul Chambers with the bow. It’s just native musical taste. I don’t think it was an educational thing. As a teenager, I was interested in what was the contemporary music of the time with Bartok and Stravinsky just the same as Louis Armstrong. They took me out into the world of sound and the thrill of music equally so.

I always find it interesting when musicians move overseas, and there was a big wave of musicians heading to Europe in the ’60s. Can you talk about that period and what made you move to France?

For my own situation, I started coming to Europe touring with bands, as many people did. I came with Atilla Zoller and Peter Nero five or six times. Due to a romantic situation, I decided to go to London for a few months at the end of a tour. While I was there, things started happening for me in terms of people saying, “Oh, you’re staying in Europe for a little bit? Why don’t you come to Paris and play with Marion Brown?” I also met the English guys and worked for many years with John Surmon, who I met during those couple months. Those couple months turned into four months and things opened more and more. In the creative world in New York, you didn’t earn any money from it. You had to gig to pay the rent and the experimental music only had occasional work; much too occasional to make it work.

Rather than leaving the states for more fertile pastures, I was in Europe for other reasons and people kept asking me to play. I couldn’t work in London very much because of union issues, but I was able to record five or six albums while I was there. Then I moved to Paris and eventually the South of France, where I’ve been for forty years. It all had to do with the work opportunity and people being interested in what my music was rather than if I could take care of a job, which was my experience in New York.

So you could be a more individual artist.

Absolutely. In the USA, it’s a make it or break it kind of thing. It’s a “one market” situation. You can be a local bass player just playing in clubs and so on, but to make it to record and sell records it’s pretty much a restricted market. Here in Europe, there are so many countries and in them so many scenes going on that you have a bigger market even when you’re playing experimental and contemporary music. You have more possibilities to play in a geographical area that is much smaller, relatively speaking, than the USA. You don’t have the same travel problems. It’s a different infrastructure, if you will, for the modern arts in Europe. So you get calls from different countries, peoples, different sets of musicians, producers. Early on in the 1970s I met Manfred Eicher and started working with him. That was also a big plus. The opportunities that came to me were not available in the States. Of course, if I had stayed in the States, who knows where the road would lead, but probably into a university.

I know you’ve told this story before, but I think the fact you recorded the first solo double bass album is amazing. Can you tell us how it came about?

At that time, I had been working for three or four years to figure out what you could play on the bass. A friend, Max Schubel, was a composer that I had worked with a few times. He called me and said he wanted to come to Europe to record a piece. He asked if I could get a few musicians together for his piece. He said, “You organize the musicians, I’ll organize the rest.” We made a very interesting album called The Sun of Quashed Culch. After that, he said, “Barre, I’m going to start to work at Columbia University in the new electronic studio there making mixed music between tape and live. I’d love to use bass sounds. Would you record some for me?” I agreed.

He set it up in a church with a good soundman. I played for probably about an hour and a half without any breaks. After that, I came down and said, “Well, that’s about all I can do.” He said, “That was unbelievable. There’s no way I could mess with that in an electronic studio, but I would love to put it out on my label.” So we put it out on the label and that really blew my mind. If I had known at that time that someone hadn’t done that already, I probably would have said no. I wouldn’t dare – that would be much too pretentious. My whole thing was to be hesitant about that, but this nice compliment from this intelligent man was convincing. I also played it for some other friends of mine and they said I should put it out. So then we edited it and made a record. He was already back in New York so it took a while to communicate using the mail system.

Lo and behold, a few years later during an interview for a jazz magazine, the interviewer said, “Of course, there’s your solo album. You do know that it’s the first one that ever happened on the double bass?” I said no, and he told me he did the research. It wasn’t a big deal for him, it was just information.

So that’s how it happened. People I tell the story to say, “That’s fantastic that the record was made and you weren’t trying to make a record. You just played what came natural and that makes it stronger.” Somehow I can say that’s true because I would have never had the idea to make a solo record and I didn’t know what producer I would use.

Had you been doing solo gigs at all?

No, I hadn’t. It all started after that.

I think that’s just amazing.

My life has been pretty amazing. Things have happened for me that I was not necessarily looking for.

Do you see all your solo albums as milestones from your life or is it just work that you’re putting out?

One way or another, they’re milestones. I’m still working today on the bass to develop technical things I can’t play. There are personal things that interest me. I’ve been working for years on spiccato bowing to develop something that is not just a reference to the classical use of spiccato. I want to find what we can play of personal music with the bow that is really your own stuff. I had done a lot of work with that in the area of playing harmonics with the bow. It’s an endless study and mastering of the harmonics on the bass. The string is so long [laughs].

So the work is going on. I was asked to make the second solo record, and that was by Manfred Eicher. Subsequently, I was asked to make a solo record in Canada. I began to see that these things were coming as milestones. Then I said, “Well, I’m ready to make a solo record.” I had a whole new group of information from playing sounds to compositional approaches that had emerged from this work. They’re like a diary. When I made the first one, I named it “Journal Violone.” It was really about a journal. Why not start a journal of your bass sounds?

The [solo records] turned out to be happening about every 10 years. Before recording End to End, it had been 15 years since the last solo record. With my age and the material I have, I figured it was time to make another one and that it would be the last one because of my age. If it takes me ten years to feel like it’s time to make a new record because of what’s developed, I’m not sure that at 95 that’s going to happen [laughs].

Well, I hope it does!

That’s very sweet of you, man. So I called up my old producer Manfred and he was very supportive and happy to do it.

Since there is so much improv baked into your music, how did you approach this album? Do you have the skeleton of a song and go from there?

It was interesting. The first day, I went through the pieces I had brought and were ready enough to put on tape. They weren’t through-composed, but they were like a theme and variations. I was looking to also do a few overdubbed pieces with a background and a melody, similar to what we had done 30 years before. We recorded those and I wasn’t very happy with it at all. I wasn’t upset at the playing, but at the concept.

So the second day, I improvised about 17 pieces over a few hours that became the bulk of the record. I was much happier because I was free to do whatever I wanted.

An experienced improviser has a whole vocabulary and thematic supply of things in his brain memory and his muscle memory to draw upon. The percentage of discovery after you’ve been improvising for 40 years is quite small – under 10% of what you’re doing. So you’re playing areas that you’re familiar with and are all in your memory. The pieces that are there are coming from my internal repertoire, if you will, but are not composed. They’re feelings and technical methods. Moods and things that are familiar to me. That particular day, those feelings came out like that. On another day, my solo playing would have another result.

For the recording, I hadn’t planned anything. When I go to play a solo concert, I start listening to myself in the hours before the gig. Once I start, one thing leads to another. That’s today. I have done solo concerts in the past with a bit more standard planning, but never with a cue sheet about what to do. It was more about the materials I wanted to play on the gig.

So at the Zurcher Gallery, it will be just about how you are that day.

That’s right. You know, the thing is that we used to play concerts, but you don’t do that anymore. You play a show. I’m not going to organize a show – I’m organizing an experience. I’m not sure what I’m going to call it, but I’m going to make that very clear to the audience.

This is your last solo album, but you’re still working on other projects, right?

Yes, I am. I’ve been working for 20 years with two Swiss musicians, Urs Leimgruber and Jacques Demierre, and we’re touring. I’m also still involved in the improvising collective formed around me about 15 years ago that is still going on. I still work with contemporary dance from time to time. It’s just because of age that I don’t have the schedule that I used to have. The telephone is still ringing and people still want me to come.