Survivor: An Interview with Benny Turner

Benny Turner’s story is the story of the blues. It’s his roots, his heritage, and his DNA. The younger brother of blues guitar legend Freddie King, Turner grew up in rural Texas during the wake of the Great Depression. His family moved as many did to the industrially rich city of Chicago when he was still a boy. That alone is a big part of the path of the blues in itself.

Turner started on guitar and first worked in Gospel, but a trial by fire on bass with his brother set his career path onto the four-string. He went on to work with Dee Clark and the Soul Stirrers before coming back to the fold in his brother’s band. Tragically, King passed soon after at the age of 42. After two years “as a recluse,” Mighty Joe Young convinced him to join his band. After Young retired, he joined Marva Wright, who ultimately passed away in 2010.

After losing so many of his friends and bandleaders, Turner changed his decades-long role as a sideman into that of a frontman. He’s recorded several albums as a leader and published a great memoir, entitled Survivor: The Benny Turner Story.

Turner’s latest release is the song “Who Sang It First,” which is accompanied by a music video. The song pays homage to the great blues musicians of the past that blazed a trail for today’s music. Focusing on his own roots, the video features Turner returning to his childhood home of Gilmer, Texas.

“‘Who Sang It First,’ is about blues history, which is black history,” Turner stated. “Shooting the music video in East Texas honors my personal history too. As a young boy in Gilmer, I rode on the cotton sack with my brother when he picked cotton. Recently I celebrated my 80th birthday at Salmon Lake Park in Grapeland. I’m proud to bring all of that history together to share an important message: never forget who sang it first and why!”

We caught with Turner to get the scoop on the song, his life, and making the leap to being a frontman.

You recently released the song and video for “Who Sang It First” – could you tell me a bit about that song?

Well, the young man who wrote it wanted Sally to let me give a listen and I did. I said we can rewrite this, so I did, and then while writing the song I said, “We can give honor to the old blues legends.” Things kind of fell into place. It was tough to write that song, you know. I threw a lot of paper away working on it. You know how it goes when you’re creating it and just doesn’t work. The night before the recording, things came together. I’d been working for a couple of months on it [then] just like that it came together.

How was it recording at FAME Studios?

Muscle Shoals is great! I can’t wait to go back. Those guys know their stuff and they have a sound. When you go in there to record, once the guy put his fingers on the guitar the other guy put his hands on the on the keyboard, you get a spirit. You can feel it. That also had had something to do with how that song came off. Those guys had just the feel with the twangy guitar and the Ray Charles-type piano. It was great.

I also appreciated the music video. That was shot in your old stomping grounds, right? Do you get back there often?

Not often. When we wrote the book, Survivor, we went back. It was like… you know, there’s a good side and bad side to how you grew up. I was born in 1939 so I saw the Depression, and all that came back. Jim Crow… I saw all of that and the good things and bad things came back. I used to hang out in cotton fields when my folks and my brother would pick cotton. In doing this song, they put me out in the middle of the cotton field. [shakes head and laughs] And the hard times and the company store all came back. Right next to it they have this little town where they had the original cotton gin, which is not in service anymore, and all of the door-to-door business has gone out because you’ve got shopping centers. It was like a ghost town and you saw that in the video.

I made the cotton sack that’s in the video. I made it to scale because it had to be the way it was I remembered it. The coolest thing was how I came up with the material because you can’t find it anymore. So I went to the second-hand store and found curtains of the exact same thing that I needed and exactly the same length. And then I made it from that.

How old were you when you moved to Chicago?

Ten years old, approximately.

Was that a culture shock for you?

Yes, definitely. [There were] no bathrooms in an East Texas and no refrigerators. When we got to Chicago we got bone-chilling cold we got refrigerators and bathrooms.

How did you feel about moving there at the time?

Once I got in it was like Christmas all year to us because of the lights of Chicago. We got there around Christmas and it was like Christmas year-round for us. I liked it, but once I got in with the neighborhood, I had to fight my way in Chicago. You can’t just be there – you’ve got to be with a group of kids. And this block doesn’t like that block, so I had to fight. I didn’t have to fight in Gilmer, Texas

Did music help take you out of that lifestyle?

Absolutely. My dad got hurt and they tried to throw me on welfare and the working situation there wasn’t that great. That’s the world for black kids, you know. They talk down to you. So when I got the opportunity to work with Freddie, I took it. Even though it was only ten or fifteen dollars a night. We’d go to work at 9:00 and wok ’til four or five o’clock in the morning – don’t make but ten dollars. [laughs] You know, I played with Little Walter and towards the end of his life, he was excited to make fifteen dollars. I mean, it was like this was in the seventies. Even though the pay wasn’t good, it kept me out of the streets and then helped me develop a career. I was about to go on welfare.

How did you get into music with your brother?

The first time we figured out we wanted to be musicians, especially Freddie, is when they would kick us out of the house. My mother played guitar and she had four brothers that played guitar. They could harmonize and sing gospel or the blues, whatever. We weren’t allowed there so they put us on the back porch – by a washtub full of beer. Freddie sat next to the beer and we’d get down on the floor to look through the space under the door. Freddie would be looking with one of his hands on the floor and one on the bottle of beer. When they finished at the end of the night, Freddie said, “That’s what I want to do.” That’s what set the stage for us to be musicians.

This is maybe a funny question but what were your early gigs like? The stereotype of blues gigs recalls Blues Brothers scenes where there is chicken wire and all sorts of craziness going on.

No, no. The gigs we played were like chitlin circuit gigs in the city. No chicken wire, but don’t hit on little guy’s girl – you’ll wish you had some chicken wire.

Our main gig was a place called the Squeeze Club on the West Side of Chicago, and the reason it was called that is a lot of people use got squeezed in there. It wasn’t that big [and had] one way in, one way out so if you got in trouble you *are in trouble – can’t get out of there. Buddy Guy came in one night to see us. Matt Murphy (MT Murphy we called him) came in. We had all the big guys come into the club. Muddy Waters was there often.

So the scene was very fertile at that time.

Yeah. You know Tyrone Davis? You know, he [hung out when he] couldn’t sing at all then. He would just sit in the bleacher section there every night and want to sing. He couldn’t keep time, right? [laughs] Finally Freddie let him sing and little but little he learned time thanks to Freddie King.

I read somewhere that you were around with Willie Dixon for the first cut of “Spoonful.” Did I get that right?

I didn’t actually go into the studio. I was at the rehearsals when they got it all together. Freddie picked me up that night and said, “Come on, go with me.” He liked to take me with him when he was going places. I didn’t know he was going to the “Spoonful” rehearsal. I walk in the door into this little room. It was the first time I’d seen all these people. Howlin’ Wolf was sitting there, Hubert Sumlin was sitting there, I don’t remember who was on the drums. Willie Dixon was on my left side and Freddie King was on my right. They counted it off and I heard Willie’s bass line. That’s when I knew this is what I want to do.

You started on guitar. What was your transition to bass like?

Strange. It was strange because when I started playing bass, it was the night they gave me the bass. I didn’t rehearse any of that stuff, you know. Freddie’s bass player was sick – his name was Robert Elam or “Mojo” – and Freddie came by and said, “Hey man, I ain’t got no bass player. Come on and play.” I said, “Bass? I don’t bass.” He just said, “Come on, come here.” Robert had just bought a Fender bass, so he took the key and unlocked it, and gave it to me.

He said, “In the key of E, so do this.” It was a one-string shuffle, you know that’s easy. So we did things like “Hideaway” and all night long we played in the key of E. Everything he did or sang was in the key of E, which made it a little easier for me. Then the next night we moved up to the key of G. Then I found my way around G, then A and B-flat and by the end of the week, man, I was like kicking you know what. [laughs] So I had Fuzz Jones and Robert Elam and all these people coming by my house. They said, “Show me something, doc!”

Once I got it, it was great. But I didn’t have a bass, so I got one of Freddie’s little guitars and we tuned it an octave lower. I wasn’t having much luck with that cause my hands are so big and when I hit that string it sounded like a rubber band. So Magic Sam’s bass player Odell [Campbell] said, “Now, you gotta hit it lightly.” He got me down and tuned it up with the strings on for me, tuned them down and sure enough, I touched him lightly and I learned how to control it. I don’t know if you play guitar, but you go an octave below, they’re really loose. So that’s what I did until I got me a Fender.

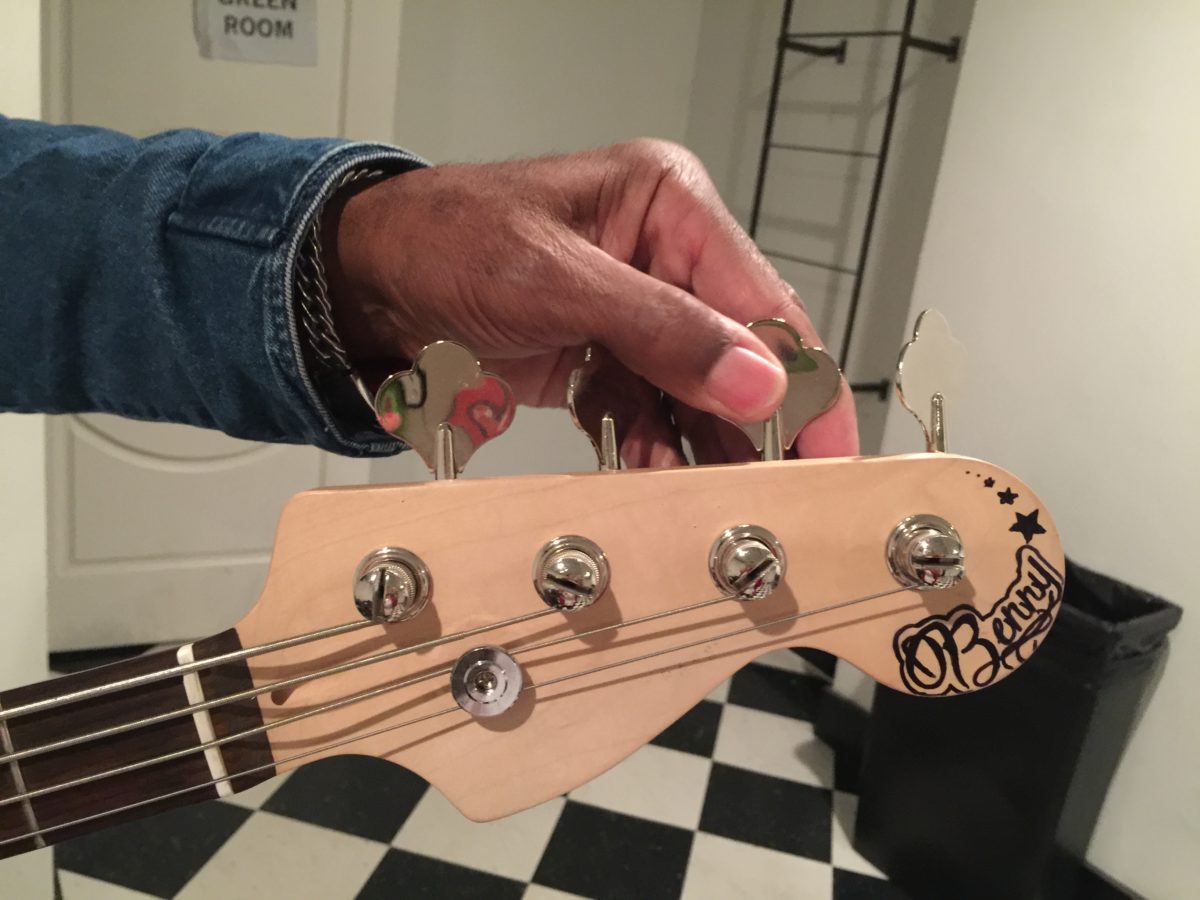

What what bass is that you’re using now? It’s pretty striking with the white finish and black stars.

That’s my main bass. The big star is Freddie King, the next star is Deacon Jones – these are all my friends – and then you got Cash McCall and you got Marva Wright. These are the people I love. You know, the people that had a lot to do with my career.

The bass is the cheapest Fender that they make it. I think it’s a Squier. My thing is it ain’t the guitar, it’s the player. A diddley bow can sound good. It’s up to the player, you know. He can up and get a better guitar, but he should be able to make the Squier play just as good as the real Fender. If he can’t do that, he’s wasting his time.

A few years ago you struck out on your own as a solo artist. What was the hardest part about that transition?

Being a frontman. If you just get up and begin a song and end a song, it’s not that big of a deal. But if you’ve got people standing out front and you really want them to enjoy you, you’re gonna

put a little more effort into it. I had to create something that would entertain people and play to the people. That was a little tough, but I’m cool now.

You seem comfortable with it.

Yeah, it’s just like riding a bike. Once you get over the hump, you’re cool. [laughs] I’m loving it and I get a good reaction pretty much everywhere I go.

I like to have fun. It’s one of the things I learned from my brother. He’d get up on stage and could be messing up left and right, but he didn’t ever get mad. He just said, “Come on, let’s go.” I never heard him get on a dude about playing a wrong note. Never. He was always about fun. I loved to see him and Mojo Elem get on stage and laugh. Freddie would drink half a pint of Hennessy and give it to Robert. He’d drink it, pat his stomach, and say, “Now let’s play some blues!” That let me know that if you have fun, people will have fun.

What does it mean to you to be a “blues man”?

I have lived it. Sure enough, I’ve lived it. Like I said we came from the Depression. When my mother was pregnant with Freddie, she saw them bring Bonnie and Clyde back through in Gilmer. We lived the blues. I had shotguns pointed at me. A guy pointed a shotgun and [pulled the trigger] the gun at me. He didn’t have no bullets, of course. But I pretty much lived it, being called names and stuff.

A lot of guys play the blues now and sing the blues. Young guys coming at it for fun and they can play good now. But you got a few people out there that have lived it, and I’m one of them. When I play the blues, all of that comes back. For players like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and people like that, it’s the same. When I was young they were still hanging people, so we ain’t got many blues guys around from that era. We have Buddy Guy and Bobby Rush, a few of those guys are left that really have experience.

What’s coming up for you this year?

[I’m working on a new album] about all of the people that had an influence on me growing up. Brook Benton, Hank Williams, just about everybody I crossed paths with. I didn’t know Hank Williams, but he was one mine and Freddie’s favorite guys to listen to.

On the radio we had Charles Brown and Louis Jordan, then the rest was country and western. We only had 15 minutes of blues, then the rest of the night was country and western so we settled on Hank Williams. My mother really liked Ledbelly.

So I’m going through all of this stuff and I’m calling it Benny’s Blues… So Far! [Laughs] I’m doing my favorite tunes that mean something, and then a gospel song by The Nightingales. They were one of the groups that set the place for groups singing with the high tenor and all that. They were one of my heroes, and when I was in New York with Dee Clark at the Apollo Theater, there was a hotel where all of the musicians stayed called the Cecil Hotel. [Lead singer Julius Cheeks] was there with Margie, his lady, and we got to be friends. Julius and I talked and talked. Then when we got down to this place called The Met, and he wanted me to play with them. Man, that was the best time I’ve ever had. I played with The Soul Stirrers, too, but that night he was playing some of the old songs that I heard him play when I was a kid. I enjoyed that so much. So I’m putting a song by him on the album, too. I’m writing a couple of songs for the album, also.