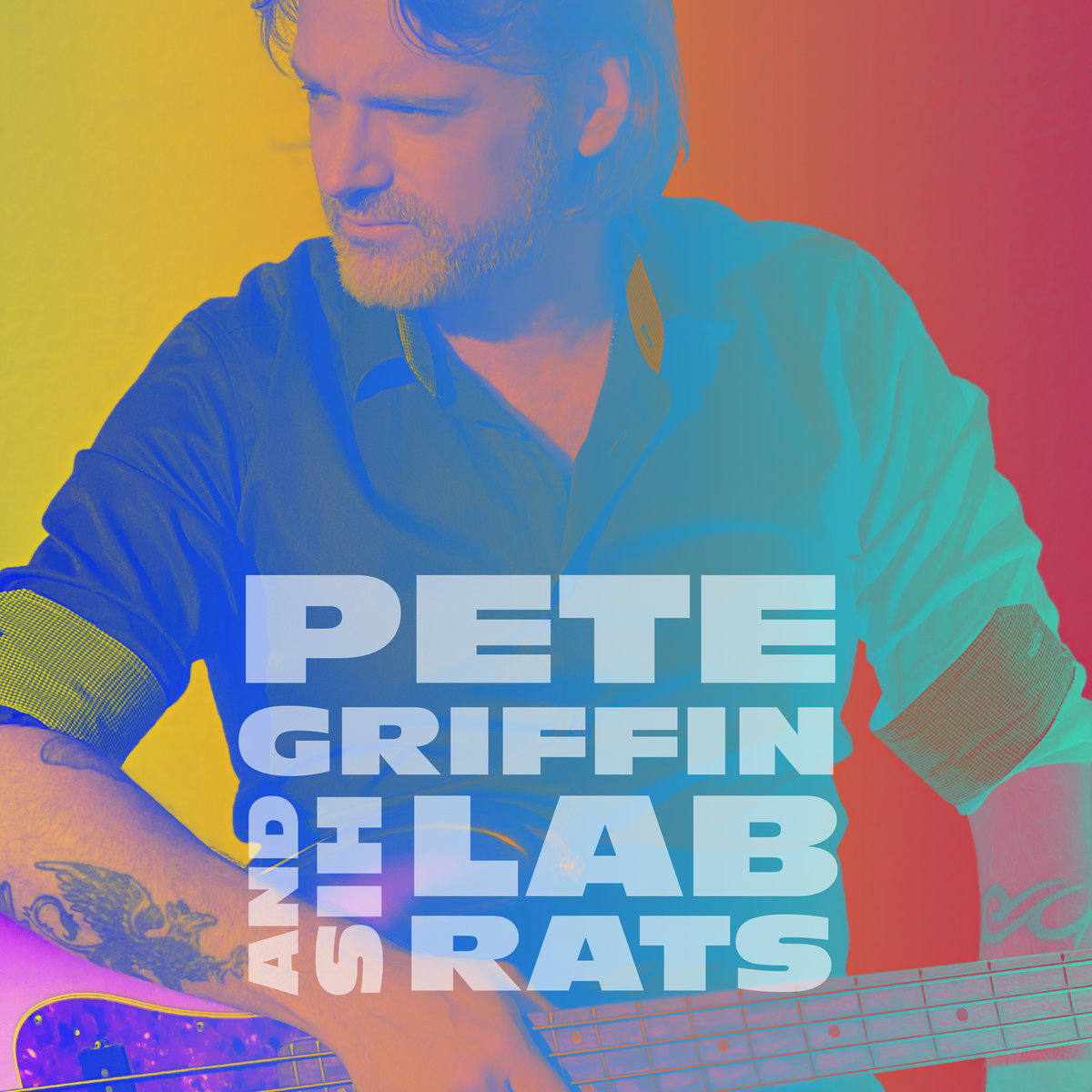

Lab Rat: An Interview with Pete Griffin

Pete Griffin has an insane résumé that includes work with Zappa Plays Zappa, Steve Vai, Zakk Wylde, Dethklok, Dr. John, and many more. While he’s contributed so much to the works of others, he has his own art to share. Over a decade after an album with his band, Gryphon Labs, the bassist has released a new EP called Pete Griffin and His Lab Rats.

The four-song collection hits the sweet spot of grooving hard while keeping things musically interesting. Most of the music is in odd time signatures, but the arrangements and production make counting the beats the last thing on your mind.

The four-song collection hits the sweet spot of grooving hard while keeping things musically interesting. Most of the music is in odd time signatures, but the arrangements and production make counting the beats the last thing on your mind.

Griffin’s affinity for odd times comes from his deep love of Frank Zappa’s music. Through learning about the ins and outs of complex music, he discovered his own voice on the bass. Now he helps others find theirs as a private bass teacher.

After catching up with Griffin at the NAMM Show, we had a video call to discuss the LA bass scene, mental health for musicians, his new album, and more.

Pete Griffin and His Lab Rats is out now digitally via Bandcamp, iTunes, and Amazon MP3.

How tight knit is the community in LA?

I see the same people in my little circuit. I always make the joke that whenever anyone asks me if I know another bass player that we’re never in the same place at the same time. Somewhere there’s a gig that does not have a bass player on any given night. So there are people that have subbed for me and vice versa, who if I pass them on the street, I’d second guess it just because we’re hardly ever face to face.

There’s actually something really cool that Derek Frank started back during the pandemic of this text chain of a bunch of bass players out here. It’s me, Chris Chaney, Stu Hamm, Whynot Jansveld, Eva Gardner, Stu Brooks, and a lot of other really great players. It’s just cool that everyone checks in. We’ll say happy birthday to each other and whatnot. Occasionally if someone says, “I need some work done on my ’65 P bass, who’s trustworthy?”, a lot of great information comes through this text thread.

It’s taught me that this whole Highlander, “there can be only one” sort of approach that I’d taken for a lot of my career of seeing other bass players as the enemy is exactly the opposite of what I should have been doing. I realized that I get most of my work from other bass players, plus most of the hangs and most of the good information about gear and the new things out there. It’s been 10 years that I’ve been thinking this, but it still was a really good 180 for me to do because I used to be like, “Screw that guy, I want his gig” and blah, blah. But actually no, he absolutely deserves it. Maybe if you play your cards right, you’ll sub for them or something like that. It’s an interesting world.

When did you start getting that like cutthroat mentality?

When I first moved out here, just because I didn’t know any better. There’s really no school for that stuff. There’s the school to get good at your instrument and there’s the school to learn how to write music, but there’s no school on how to hang and how to be a nice person.

In most of our situations, the playing of music is actually the minority of your time. I did a tour maybe 10 years ago with a thrash metal band called Three Inches of Blood from Canada, and we were opening for Death Angel. We’d play half an hour every day. That was it; no sound check. So actually playing bass on stage was 1/48th of my time on that tour. And the other 47/48ths is sitting around. And usually not in the best of situations… Maybe it’s a tiny dressing room or there’s no food.

You have to be self-sufficient and be able to hang, but also take care of yourself and stay healthy. It’s easy to spiral out on loneliness and depression that can come up when you’re touring or even just making music around town. There’s a mental aspect to it that we all have to remember and if you can get along with the people that you’re working with, that is so much easier. That has nothing to do with musical skill whatsoever.

I say all the time that there’s dozens if not a hundred people who can do pretty much any gig that I do or any gig anybody does. It’s a matter of that other 47/48ths of your time. Are you okay? Or are you only cool when you have your bass on and then the rest of the time you don’t know what to do with yourself? I read a lot, I play a lot of silly mind games on my phone to keep my brain sharp and just use the downtime in constructive ways rather than spiraling out on social media about the gigs and that you don’t have.

It’s really dangerous. Especially for these days now that mental health is something we should all be talking about a lot more. We don’t really get into that nearly as much as we should in terms of other people. I was talking with Scott Kinsey, the keyboard player, about how we have the only profession where we really just can’t call in sick ever for whatever reason, either physical or mental. We can’t really say, “Guys, I can’t do the gig tonight.” We just cannot do that. We have to do the gig no matter what. We all learn how to power through, but all the rest of the time, we should check in on that stuff more.

I’m guilty of it, too. Everyone puts their best life on social media. People who haven’t seen me in a while will say something like, “You’ve been busy!” And I’ll think, “Have I? I don’t remember getting off the couch the last couple of weeks, but sure.” It’ll turn out they’re thinking of something I posted from a month and a half ago where I was doing something cool, but that’s not our lives all the time. We’ve gotta remember that.

Another big one and another thing I tell my students is that you can’t have every gig. You just can’t. That alone is sort of a liberating thing. We really just don’t have enough time. Usually it’s feast or famine. I haven’t been on tour really in almost five years. I’ve done plenty of work around town and all that stuff, but I haven’t been touring. Suddenly everything is coming up where I’m doing a Dethklok tour, then I was offered another tour that would have conflicted with it. There’s this other thing that happens right after it that I’m gonna have to hustle to get the music together for. It’s one way or the other and you just have to ride out the low parts and remember that the high parts are coming back, ideally.

We need to user our time creatively rather than negatively in terms of “Why does that person have this gig that I want?” It’s so easy to fall into that. Comparison is the enemy of joy and creativity. As soon as you think either I’m better or I’m worse than that other person, we’re not being creative anymore. We’re not being artists. We’re being sports people and I’m not into that at all. Every time I start worrying about why someone got the gig and not me, I think about all the gigs that I might not be that into that I have, but I’m happy to have them. There’s someone out there with a voodoo doll of me sticking pins in my hands saying, “Why does he have that gig and not me?” It’s very cyclical.

The mental health aspect of it is not insignificant, especially these days now that we’re all expected or even required to be self promoters as much as anything else. That was not something I was raised on the other than going to gigs, jamming with people, showing off that you’re good at what you do and that you have cool ideas and things like that.

Speaking of mental health, do you have any like go-to self-care routines when you feel yourself drifting?

Yeah, great question. A lot of it is to not be so hard on yourself. My wife said that to me back before she was my wife and it was kind of the moment I fell in love with her.

It made me think, “Why am I so hard on myself?” I’m the only one doing it. Nobody else is really comparing me to these other bass players that have tens of thousands more followers than me or a bigger gig. No one else is saying “Why aren’t you like them?” You’re the only one doing that. That’s easier said than done, obviously.

Try to keep it light and remind yourself that everybody needs to take a break from these things. Our worlds are so entwined in this public figure concept that a lot of us, especially us bass players, never planned on. We’re the least narcissistic guy or girl in the band and we want to be on stage. We want people to notice us, but we just want to be in the back. We’re not looking to have the mic in our face the whole time. At least that’s my approach.

These days we’re losing more and more musicians that seemed like they were doing great. Depression is such a silent killer and people just need to talk about it. I’m so glad we’re actually talking about it because it has been my cause lately. I want everybody to talk about. It shouldn’t be that stigmatized that you have depression or anxiety. We all have something, it’s all different sides at the same coin.

We all struggle with it in one way or the other, it just depends on what you call it. It’s good to recognize that, “Wow, I’m having a depression day. I need to do the things that pull me out of that, even if that means not doing the things that are adding to it.” As soon as you do that, maybe a few hours later, you’re fine.

Everyone has their own approach and their own way of dealing with problems and dealing with happiness and banking the happiness. It’s important to remember that you are not just who you are in this particular moment. You’re an entire human being.

All of this seems to lead into your album because it’s finding your own voice. Do you feel like the mental health aspect played into making the album or were you just compelled to make it?

It was a little bit of both. It was very much my pandemic project. So I figured I needed to do something with this time as if it was my job. So I learned how to make breakfast and other aspects of contributing to the household. And watching The Price Is Right, which I recommend to everybody. Watching some college kids win a car is like taking an antidepressant in the morning. It just makes you feel good.

Then I realized, wait a minute, I’ve got a studio full of cool stuff. I’ve got great basses. I’ve got cool synthesizers. I’ve got Logic, which has everything you ever need in it. Let’s work on music! I made it my job.

And you’re right – I had all these ideas. But for more than 10 years, I hadn’t really worked on my own thing. Every time I sat down to listen to music or play bass, there was something I was supposed to be doing. There’s always something I should be working on. There’s a song I should be learning. There’s a style I should be mastering. I was sweating all of that instead of thinking about what can I make, so I started going off on that.

One of the tunes, which I think is the single from that EP, is the song “We Come From the Fire.” I was just messing around this thing called a charango, which is like a South American mandolin. I came up with this little part in five as we were just watching the news. I just kept playing it over and over again. I was like, “That’s pretty cool.” I ran back into my studio, tracked that and then this entire song blooms out of that one little moment of tracking that idea down.

I decided to produce it all myself, too, where every single decision about tone and placement and all that stuff was me. As much as my career has been great in terms of albums I’ve played on and tours I’ve done, I feel like my fingerprints are not on as many things as I’d like them to be. I’ve done a really good job of listening to the producer and getting them to get a good performance out of me, but it’s still filtered through them. These four tunes are me playing the way I want to play, me arranging the way I want to arrange, me writing the way I want to write. I know it’s not going to be enormously successful, but I kept running into stuff recently where I had been sitting on it for a while and so worried that about the millions of people that weren’t going to hear it.

I started doing some gigs with a few bands and I had a lot of people come up to me and say, “I really love your playing. Do you do your own stuff, or what happened to your old band?” That touched me in such a deep way where I thought, “Wait a minute… Why am I so worried about the millions who aren’t going to hear it when there are a few dozens who are begging me to hear it?”

That’s amazing and super inspiring that I’ve made enough impact. I have no delusions about how wide that is, but at least a handful of people are out of the blue asking me for this thing. And that’s like… I’m getting emotional thinking about it. It’s really amazing that these people give a crap about my art and not just what I’ve done for other people. That really was the inspiration to keep doing this.

The best part too was I know a lot of really, really good musicians who also were home with not much to do during that time. So I made demos of everything and sent it out. Of course all the stuff I got back from everyone was just so cool. And you have to be okay with it sounding nothing like the demo, obviously, but that’s the whole point of getting a professional. We do it all the time in the opposite direction where we’ve got someone’s MIDI bass and then we basically play the same thing, but do we really? We add a lot of, we add our humanity to it.

What’s amazing is on the tune “Trapped in a Fishbowl” the first part is in 7/8. I had a very repeated drum part, and Gergo sent it back to me where the kick pattern never repeats. I was playing along with it with my now very boring sounding three note bass line while his is doing all these accents and stuff. So I erased that and then learned his kick drum part as the part, which I will never be able to play live unless I chart it out and read it. It’s not like it’s difficult, but literally every bar is a different syncopation of one or two kick drum hits in 7/8. Remembering that is gonna be nearly impossible, but at the time it sounded way cooler.

Then because he brought so much more energy to it than what was on my demo drums,

I had to play more. I had to break out the thumb and do more Claypool, slappy stuff to match that energy. It that took a song in a completely different direction.

You’re into the odd meter thing, aren’t you?

Yeah, that’s one of my things. My early exposure to Frank Zappa in high school caused that. I had an older brother who showed me a lot of Genesis and The Police and cooler stuff than I would have been listening to as a 10-year old kid in the ’80s.

Odd time signatures have always appealed to me. I call my music fusion for the masses because it does have pretty bizarre time signatures and some solos, but it’s enclosed in a pop song format. It’s still verse, chorus, verse, bridge.

On this album, I got a little longer. There’s the seven-minute tune and stuff like that, but in general it’s not super dense or too hard for the average person to wrap their head around.

The idea is that if put it on for a non-musician, they should still be nodding their head. Are they still feeling the groove? That’s exactly how I approach all odd times signatures. I’m never counting. You just start feeling either where the snare drums are or something about the groove that is just as natural as 4/4. No one counts to four when you’re playing 4/4. You just play 4/4, it’s burnt into us.

Do you have any tips for bass players for making odd meters feel comfortable?

A lot of it is a physicalizing of it in some way or another. I conduct myself with my head. My chin’s always going up and down or I do a little side to side thing or both. When you do that you start to see the larger picture. It can be a bar of 7/8 or it can be two bars of 7/8 which is really a bar 7/4, and you know, all that larger math.

You never want to count up to the full number. You always want to either break it up into three beats and then four, or four and then three, five and two, six and one, whatever. Because then it’s easier to think of it as two grooves smashed together in that way. It will feel like you play a four beat thing, then a three beat thing, and then repeat that.

Eventually you start to develop a dance that goes with it. I am in no way a dancer, but I can feel how much time has gone by according to my little dance. It shouldn’t feel like a wheel fell off the car or something. We want to keep it smooth.

Some of the best examples in pop music are “Solsbury Hill” by Peter Gabriel and “Money” by Pink Floyd. “Money” is bizarre. It changes time signatures constantly throughout that song, but people don’t know that. Anybody can just sing you “Money” because it’s not so herky-jerky.

One of the most famous examples of a jarring but awesome groove is the end of “Keep It Greasy” by Frank Zappa off the Joe’s Garage album. It’s in 19/16. You can’t count to 19 for every bar. The way you approach that one, at least the way I do it and you can hear that’s how they’re doing on the record, is playing 16/16, which is 4/4, plus 3/16. Once you get it, it’s still very odd, but you can just get that loop going and you’re not so worried about falling off the track.Then Vinnie Colaiuta starts doing his thing or Joe Travers, who I play with on that stuff, starts doing his thing. They can flip it upside down and backwards and you’re still cool.

It’s exciting once you really start wrapping your head around it, but it takes a bit of work.

I know that besides making music, you teach lessons. Do you enjoy it?

Definitely. What I like about teaching is I don’t just have formulaic lesson plan. One of the first questions I always ask my students is “What kind of bass player are you trying to be?” You don’t have to have an answer, but it’s something to always think about. Are you trying to be like me where we play a different thing every day and it’s a different style of music and we’re reading a lot and we’re fitting ourselves into different situations?

Do you want to focus on just weird odd time signature music that you want to make and focus on your voice? In that case, we’re going to skip over a bunch of stuff about a general bass tone, how to sound like James Jamerson and all that stuff. That’s irrelevant to this person.

To have a school of my own where I’m just cranking out more and more of the exact same cookie cutter bass player, I have no interest in that. You can’t just stick everyone in a box and expect it to work for them.

One of my favorite things is having someone show me something they’ve written. Then I reverse engineer it and explain to them what makes it so cool.

That’s what’s really amazing about music and the educational aspect of it. We have to remember that as much as I went to music school, someone can come along and have never spent any of that time and still play something beautiful and amazing and even something that we couldn’t be able to do or even necessarily understand. For so long that frustrated the hell out of me, but then we go comparing ourselves again and we can’t do that.

Teaching has made me better in so many ways and it keeps me connected to what other people are doing with music and bass playing.

Is there any music or any bass players that have been exciting you lately?

Yeah, I love Meshell Ndegeocello. I always have. Her latest album is yet another masterpiece where she’s a perfect example in terms of the teaching thing where we learn rules and then throw it out the window. The rules are you play the root, play it on beat one, you do that over and over again. She’s missing beat one all the time. She’s not playing or she’s playing out of time entirely and Goddamn if it isn’t the coolest thing I’ve ever heard in my life.

But we gotta learn those rules first and then break them. As we know, it’s such a cliche, but it’s absolutely true.

I love this guy, Jason Gray, who plays in a band called The Polyrhythmics. They’re a throwback funk band and I love his tone and his approach. People talk about seeing these musicians who can play millions of notes. I wish I could play as few notes as he does. His restraint is as inspiring as anything else. Same with Meshell to a certain extent. You know, like why play 20 when you can play two and it’s just as effective if not more so.

I still check out a bunch of the newer metal and punk bands and I like a lot of electronica stuff. I wish I could say I had another list of cool bass players that I’ve been digging but I don’t really listen to bass players that much anymore. I listen to producers and things like that.

I am still such a huge fan of all of Frank Zappa’s bass players, specifically Scott Thunes and Tom Fowler. Tom Fowler, geez… On some of the more recent things that they’ve released from his time in Frank’s band, his tone is just so crushing and he’s like the loudest thing in the mix. And he’s playing these ridiculously hard things. He’s sort of a forgotten name in terms of amazing 70s bass players. Everybody knows Stanley Clarke and Jaco and Alphonso Johnson and all that stuff. Guys like Tom Fowler and Patrick O’Hearn followed him in Frank’s band and played a fretless P bass, which is why I got a fretless P bass because that’s the coolest sound ever.

Everyone goes the Jaco route in terms of fretless with the back pickup on the J bass. You hear Patrick O’Hearn or Percy Jones or some of those guys and realize it doesn’t have to be just that. We can be fretless and still have some nice girth to the tone and all of that. So I still get inspired by a lot of that stuff.

On a different note, you’ll be on the road with Dethklok in April. How are you preparing for that?

As far as I know, it’s very similar to the tour we did last year in terms of having a lot of the same songs, but I know we’re adding a few new ones.

Last time was interesting because I had to jump in most of the way through the tour. I had been practicing this stuff at home with a live recording so I could hear the way it all sounded and get the sort of breathlessness of the way the set was lined up. We would end the song and like not 10 seconds later start another song. So it’s not just a matter of learning all the songs, but the flow of it. Once we finish a song, I think, “Do I need to tune? Do I need some water?” Too late! We’re already on the next song. Not being able to even like catch your breath in some ways was the hard part. So I’ve got to get those muscles back going.

And it’s different gear that I use for Dethklok because everything’s tuned to C standard. So I have a Dunable that has a 35-inch scale and I recently got a Dingwall D-Roc that I love for that stuff. It makes a C-string feel like an E-string in terms of the tightness and the responsiveness.

Directly after Dethklok I get to do a gig with Bear McCreary, who’s this big time TV and movie composer. I’ve done a bunch of work for him, but he did the Lord of the Rings show and he did all of The Walking Dead. He’s finally releasing his solo album, which is gonna be a pretty big deal. I didn’t play on the record, unfortunately. Bryan Beller played on a bunch of it, and John Avila from Oingo Boingo. His slappy stuff is what I need to be working on right now, actually. So while I’m out with Dethklok and I’m not on stage, I will be practicing that stuff for a gig in May with Bear that will hopefully lead to some more things like that.

But for Dethklok, I’m just getting the picking hand going again. I’ve actually finally learned some three-finger technique because that’s Bryan Beller’s approach to a lot of this stuff. It’s interesting that he and I play a lot of the same music with completely different approaches. You know, he takes a B-E-A-D set of strings and tunes them up to get to C. I take the Dunlop Heavy Core 55’s and drop that down to C. So there’s one way already that we approach the exact same songs a little differently. So I’m just getting that back going again and getting the pick hand and making sure it’s nice and tight.

It’s so much fun. That’s tour is such a blast, just being a part of a huge production and standing next to Gene Hoglan, who is a literal god of metal drumming, and watching him do his thing. I remember one of the first days in rehearsal 10 years ago when I first toured with him, he may have messed something up – we’ll put it that way – and I was like, “Thank God, he’s human.”