Gonna Take More: An Interview with Rustee Allen

As a pioneer of funk, soul and rock and roll, it would be easy for Rustee Allen to rest on his laurels. In 1972 he filled the mighty big shoes of Larry Graham in Sly and the Family Stone with whom he toured and recorded hits like “If You Want Me To Stay”. Then he took up with blues rock icon Robin Trower, again touring and recording albums. He’s worked with The Temptations, Bobby Womack, Lenny Williams, George Clinton, and more.

But none of that success keeps him from being the best version of himself he can create.

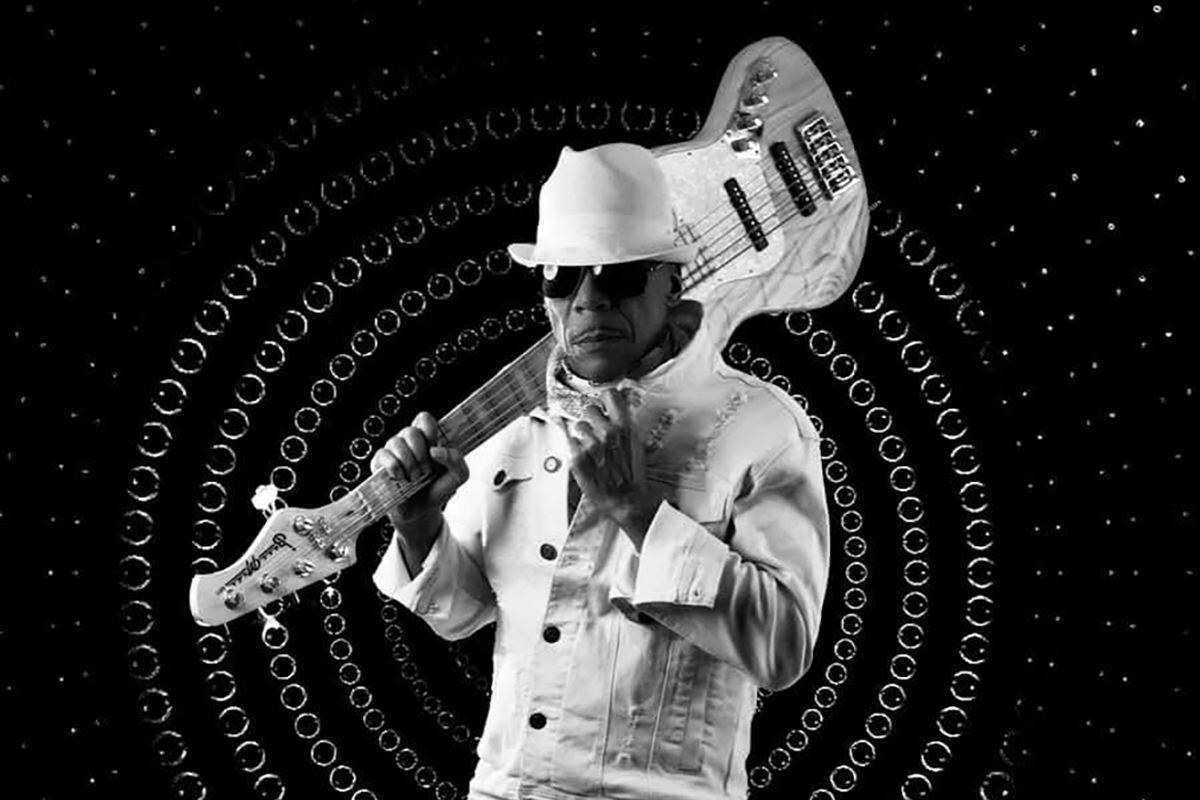

Allen released his solo debut EP called Simple Rules in 2019. The album features Clinton and Womack as well as Freddie Stone and other special guests over the bassist’s slick compositions. (It also has a great re-imagination of “If You Want Me To Stay”.) Now Allen has returned a new single called “Gonna Take You More” with vocalist Dee Dee Simon providing a lyrical flow over a perfect R&B groove.

More than creating new original music, Allen tells us that he’s continuing to hone his skills by expanding his horizons. He’s been studying the upright bass in both jazz and classical concepts. To know such an accomplished bassists has never stopped learning had me leaving this interview humbled and inspired.

Read on to learn about Allen’s wild early gigs, his insane audition for Sly and the Family Stone, the enormous bass rig he used with Robin Trower, and more.

“Gonna Take More” is streaming now via iTunes, Amazon MP3, Spotify, Bandcamp, and more.

Thanks for taking the time to chat. I’m always in awe of heavyweight players like yourself from back in the day. Your time with Sly Stone and Robin Trower and Bobby Womack makes you part of the bass world history.

It’s amazing that you say that. It’s hard for me to wrap my head around it. Not that I took it lightly or that it’s insignificant, but because it’s a reality that I have a hard time dealing with sometimes. I’m humbled by the experience and I’m humbled to be part of that vanguard from the ‘60s and ‘70s and part of that whole bass movement. I’m just happy about it.

The bass guitar as it is now was only around for 20 years when you were playing with Sly, so there was still a lot of exciting experimentation happening. What kind of music was going on and what players were around as you were coming up?

I really didn’t have an acute awareness of the players at the time I started listening. I was maybe nine or ten years old, but I distinctly remember mom playing records by Ahmad Jamal and Ray Charles and John Lee Hooker, people like that. It had a profound effect on my spirit and how it made me feel. I can think of those songs right now and get a similar feeling from it.

You picked up the bass at fourteen. Did you start on guitar?

I started on guitar only because I didn’t know what a bass was. I’d be playing with my friends and they would say, “Someone has to play the low notes,” so I would just play the first four strings of a guitar. Later on I discovered that there’s an instrument that only employs four strings and it’s called a bass. [laughs]

When you started to get into music yourself, was it the stuff your parents were listening to or was it the rock scene or soul?

A little bit of everything, mostly though it was soul and blues. We were listening to Chuck Berry and John Lee Hooker and James Brown. When James Brown started really affecting me, it was like wow. But then Motown came onto the scene with James Jamerson and all that thing. By that time I was sixteen or so.

I remember me and my sister were listening to “Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day” by Stevie Wonder and I was just so impressed with James Jamerson’s playing. I wrote a letter to Motown saying, “I want to play for Motown!” They sent me a letter back that said to visit anytime I was in Detroit and we could talk about it. I was too young and wasn’t about to leave Oakland, but that bass playing and that approach really riveted my whole attention span.

When you were learning to play, were you self-taught or was anyone showing you stuff?

It’s funny you say that. It was all just ear, man. No grade school band or none of that. I just remember my dad’s brother coming over to visit with an acoustic guitar. He’d play a little thing on it and he’d ask me if I could do it. He handed me the guitar and I immediately played it. That was the beginning of it.

[My friends and I] would just go out to try to play little talent shows and do James Brown songs and Booker T. & the M.G.’s and stuff like that.

What do you consider your first serious work?

My first serious work was with a guy named Johnny Talbot. He was from Texas and he had a band called Johnny Talbot and De Thangs. They were like a funk band. Good singing, but those guys [were amazing musicians]. The drummer was Lamont Scott was from New Orleans so he had a groove that was stupid good. As they would play, the funk would just evolve. They were kind of holding down the Bay Area. Along came Marvin Holmes and the Uptights and Eugene Blacknell and the New Breed and all these bands, but Johnny Talbot was at the forefront of all these guys.

I was hanging out with my buddies, riding around in a car on a Sunday in West Oakland. I looked up and saw this guy getting his shoes shined at a booth outside. I said, “Stop the car, man!” It was Johnny Talbot. Just like with Motown, I went up to him and said, “I’m going to play for you.” He must have thought, “Who is this crazy young dude?” But he employed me and the next thing I knew I was part of his group.

He nurtured me, teaching me the blues and the seriousness of being a musician. He instilled a lot of good values in me as a musician and as a man. I still communicate with him on a weekly basis.

I cut my first record with him. They were cutting 45s in those days. I played on a record called “Git Sum” and another one called “Pickin Cotton.” There was another called “Take It Off.”

I got to play in clubs and travel a little bit. I was still in high school, so as a matter of fact in the 11th grade I went ahead and got a GED to get my diploma. I said, “I’m done with school. I’m ready to play.” I was well involved by that point. I would be in biology class and nodding asleep at my desk because I had played at the campus club the night before. I was smart enough to take the GED and get flying colors, so I went ahead and did that.

How did your parents feel about that?

My mom was one of my biggest supporters. As I said before, when I realized there was this thing called a bass guitar, she bought me one. She even tried to get me some lessons in Alameda, but I just wanted to play. I didn’t want to sit there and study chords and scales.

She bought me my first bass. It was called a St. George, which was like a Fender Jazz Bass copy. She bought me a St. George piggyback bass amp, which was also like a Fender bass amp. I had me some gear, man. [laughs]

I remember my first road trip. Johnny Talbot came to my house and picked me up at about 2am. I jumped in the car with him and went to Phoenix, Arizona and my mother didn’t even know. He called her and told her I was with her, and she said as long as I was with him it was ok.

I saw some stuff at a very early age, man. We were playing this club in Phoenix on Buckeye Road. It was a juke joint type of place where people were drinking bottles of Robitussin and guys were coming in with guns and everything. They’d point guns at the stage and say, “I wanna hear such and such song, you’d better play it right now.” I said, “Jesus, is it really like this?”

That’ll make you grow up pretty quick! I don’t think I could have hung in there that young.

Something burned in me that I just wanted to play. It just fulfilled my spirit so much that I couldn’t let go. The more and more I did it, the more and more I wanted to do it.

Did you meet Sly Stone while you were working with Johnny?

Actually, while I was working with Johnny, I met Larry [Graham]. He would come and listen to me play with Johnny in little local clubs. He would sit at the table and just watch. I knew who he was only because when I was in Sobrante Park, I’d look out my living room window and see this guy going to see his girlfriend across the street. He drove a Buick and he would get out of the car with this long case. He had a James Brown pompadour hair style and suit and tie on. I thought he looked so cool and just wondered, “Who is this guy?” Well, it was Larry way back then. So when I saw him in the audience, it terrified me. [laughs]

I’ve said time and time again, it seems like the steps were ordered just right to end up with Sly. As a kid, I was totally into him and his radio programs. I would just lay and wait for him to come on the air. His delivery as a disc jockey and the songs he would play just made a great experience. I just loved the dude and his whole thing. Never in a million years would I have thought I’d be playing bass in his band, but it happened.

What was it like the first time you met Sly?

I was playing with a band called Lighthouse for the Blind. Freddie Stone had given us that band name. It was Willie Sparks, who went on the play drums for Graham Central Station, and David Stallings, who went on to play guitar for Lenny Williams. We had a little funk power trio. Were were playing Grand Funk Railroad and little things that Sly and Freddie had written.

One day we were up at Freddie’s house and to everyone’s surprise, Sly and Hamp “Bubba” Banks pulled up. Freddie said, “Sly is here,” and I thought, “Wow, I’m gonna meet Sly for the first time.” I go to the bathroom, and as I coming back he’s coming down the hall to go to the bathroom. I just walked right past him. As I pass him, he turned around and said to Hamp, “Man, dude didn’t even look at me.” [laughs]

I think because I didn’t act like I was worshiping him, he could feel something was different about me. He didn’t know that I was a bass player yet. It wasn’t until he saw me with Little Sister that he realized it was me.

I finally got to really meet him via the telephone. At that point, Larry had left. We talked a little and he was asking me a bunch of questions. His voice was so deep and resonant on the phone that I couldn’t understand a word he was saying. All I knew was that I’d better say yes to everything. [laughs]

He was a great guy. It was like I became part of the family. I wasn’t just the bass player. I was like a sibling. He loved me that way and I loved him.

Your first record with him was Fresh. Had you been playing with him before that?

No, but I had been playing with Little Sister then and we had been opening up some shows for Sly. Larry had left and had recommended that I play for the band. At the time that we were recording, I was basically already in the band. That’s another story, too.

[For the audition], we were in Roanoke, Virginia in front of 20,000 people. It was me and two other bass players taking turns playing. It was crazy. It felt like we were auditioning in front of a million people. But I ended up with the gig. I think one of the main reasons was that I was already tuned into how they were attacking the bass and how their funk went, because I had been doing it. When I played, I guess they felt that feeling and pressure and sound.

I wanted to ask you about the actual recording situation. I know you’ve mentioned before that you would lay down some bass and Sly might come in and dub in little parts he wanted. What was the atmosphere like? And what kind of gear were you running?

That was one of his techniques. I would play something and he might enhance it. “If You Want Me To Stay” was like that. “Organize” on the High on You record was like that, and then some other tracks he just left the way they were.

The atmosphere was great. It was the first time that I had used the technique of sitting in the control room and plugging directly into the board. With Johnny, everything was in the studio with baffles and it was all live.

For the most part, I would just cut tracks directly into the board or I would sit in the studio by myself with an Acoustic 360 mic’ed up with my Fender Jazz. It was no pressure.

Around that whole camp, you had to just step up and be that dude. You can’t be intimidated by nothing. I figured that out as our relationship grew. If I wanted to talk to him about something serious or personal issues, I had to call him Sylvester. That kind of reeled him in. If you address him as Sly, then he’s that guy. So I figured that out and it worked.

Are there any particular gigs that stand out from tour?

There were so many good ones. When Andy Newmark was there, we just clicked on a crazy level. I can’t just pick one out, but I will say that some of the Ohio gigs with the Ohio Players in Dayton, Columbus, and those kind of places were special. We were in the dressing room and Sly gathered us up. All he said was, “You all know what we’ve got to do.” That was it. From that moment on it was just straight fire. I remember Billy Beck came to my hotel room and said, “I’ve never heard anything like that in my life.” Those gigs really stood out to me, but there were really a lot.

The funk coming out of Ohio in those days was really killer. Was it a matter of competition?

Yeah, you know. The Ohio Players were good, man. Before I got with Sly, they came to Oakland and played at a club called The Showcase. That’s when they had “Funky Worm” out and Junie Morrison was with them. They had a sound, but Sly was setting trends and affecting culture all over the world.

Sly has an autobiography coming out. What are your thoughts on that?

It should be full of some very interesting situations and scenarios. I just recently did a segment with Questlove for his followup to the Summer of Love documentary about a month ago. But Sly’s memoirs should be some serious reading. If he just exposes everything, it’s going to be like…. wow.

He’s one of the few black entertainers that was featured in Playboy magazine. I remember an article in Rolling Stone saying Sly would get a cool million per project and all he had to do was turn in the tapes. I thought that was crazy. I felt like I was in the funkiest band in the world and it was never going away. Boy, was I wrong. [laughs] But it was a great experience.

Like I said, I have a hard time wrapping my head around the historical value of it. People talk about me playing with Sly and I say, “Yeah, but that was then.” It’s not like I downplay it. Life goes on. What’s going on today? I’m here with you! That’s big.

I feel like the transition to playing with Robin Trower was a big change in sound and style. Was that an easy move for you?

It was so easy. Playing with Lighthouse for the Blind, we were playing Hendrix and Grand Funk and Buddy Miles already. When I got to the band and Bill Lordan was there, we clicked. It was amazing. I was into the music. Jimi Hendrix still is one of my favorite guitarists of all time. Eric Gales to me is like Hendrix reincarnated and he’s my guy now, but I can still listen to Hendrix and get the same feeling as I first heard it.

We had some great gigs. I had no idea we were playing with that much firepower until I heard us on the King Biscuit Flower Power Hour from New Haven, Connecticut in 1977. Check that out.

Just listening to Trower’s music before you came in and after the two albums you’re on, it seems you brought a whole new vibe to the music. Was it open writing with him or he just knew a sound he wanted?

In an interview he did with Rolling Stone, they asked him about funk. He said, “I don’t want to get submerged in it, I just want a taste of it.” That was my sound and feel anyway, so I didn’t have to do too much. I had a free reign as far as feels and creating dynamics and things like that. He never told me not to do something. I felt that freedom while pushing 2,000 watts and a bunch of speakers. It was great. It was kind of what I always wanted to do with Hendrix.

What kind of amp were you running?

I had some Cerwin Vega folded horns, some front-loaded JBL 4x10s, some Crown power amps, some preamps, a bunch of stuff. I had a wall behind me.

Getting to your own music, your 2020 EP Simple Rules was your debut solo record and your first solo band show was the album release. How did it feel to be the frontman after so many years?

It felt pretty cool. I always thought I could hold a band together and create some excitement on the bottom end. Being part of that pop and funk vanguard I knew I could do something if I just had some decent players and some decent songs. I had no hesitations about it. I plan on doing it more, but getting good players is hard to do right now where I’m located.

Have you been writing music or did you just have a recent burst of creativity?

I just came up with some lines and collaborated with people for hooks and lyrics. I came in with the bass lines and guitar parts. Levi Seacer, who played guitar for Prince and the New Power Generation, we play together in a Prince tribute band called The Purple Ones. He did the mixing and was in my band for the album release.

I write in spurts. If something comes to me and I remember it, then it’s worth checking out. But I don’t write a lot of things down. If something comes to me and I can go to sleep and remember it the next day, then it’s worth checking out.

Right now I just have a bunch of bass lines and drums recorded. They’re raw right now, but I’ll see where it goes in the future.

Are you thinking a full-length album or just singles from now on?

I would love to do an album, but the state of the business doesn’t pan out profit-wise to sink a bunch of money into making a full album. If you’re not a big wig at a big company then you’re just one of millions of fish in a bowl. I probably will continue to do singles and if one takes off, that will help catapult an album.

Your EP has some heavy hitters on there – George Clinton, Bobby Womack, Freddie Stone… Are you going to do some more of those collaborations?

Possibly. I’d just like to incorporate some good energetic people to sing and some good funky players. I wanna get up there and have fun. I love what Thundercat does. Bass players out there now have taken bass playing to such a level it’s like a science.

I often think about Larry Graham. You had no idea that they’d be analyzing your bass style like this – popping, plucking, picking. Then guys are hammering like Van Halen. I can’t do all that, but I can make people feel good with some good time funky music.

Your latest song “Gonna Take More” has such a great bass line. The space in it makes it feel so good.

I ended up simplifying it to that point because it had a little bit too much going on. We had been listening to some D’Angelo stuff so we grabbed his snare drum sound and the bass drum and I simplified the bass line and it worked. Levi did a great job mixing that. Dee Dee Simon came in and her interpretation was on point. She was done in 30 minutes. She just came in and nailed it.

What words of wisdom do you have for bass players out there?

Someone recently asked me about technology, and I say use it. Transcriptions are easier now. You can slow down a track and it doesn’t change key. Sibelius prints out your writing. Then you have thousands of talented players on Instagram and YouTube giving tutorials. Take advantage of all that.

The next thing is don’t think that you’ve arrived. Learning does not stop. As a matter of fact, when we get done with this interview I’m on my way to Delta College to practice with the Symphonic band, then I’ve got a recital today for a piece that I’m bowing by Vivaldi. I’ve been playing in the symphonic band, jazz combos, and jazz orchestra for the last three years at Delta College. My point is that it doesn’t stop.

That’s amazing! So you’re playing upright?

Yeah, I’m loving it. My mom always told me, even when she bought that bass, that I should learn to play the upright so I would survive as a musician a lot longer than just playing the electric. She was wrong about that, but she was right about the upright.

Another thing is that to be a functioning bass player, you’ve gotta be able to read something. You have to know how a chart works and read the signs. If you wanna be a cat, you’ve gotta put the work in. If Victor Bailey was alive, he’d tell you the same thing. Victor Wooten, Daric Bennett, Henrik Linder, all these guys did the work. I can’t play like them because they are them, but I can always get something from listening to them.

Don’t stop learning and don’t stop yearning.