The Concert of Europe: An Interview with Jonas Hellborg

When you look at Jonas Hellborg’s career, practically every project he’s played on has been a mighty gathering of musicians. He was a member of the ’80s lineup of Mahavishnu Orchestra, and he played on the first Public Image Ltd album. He collaborated with Bill Laswell, recorded with Tony Williams, and had a longtime project with Shawn Lane. The list goes on, but there’s one project that really caught me off guard when he told me about it at the NAMM Show.

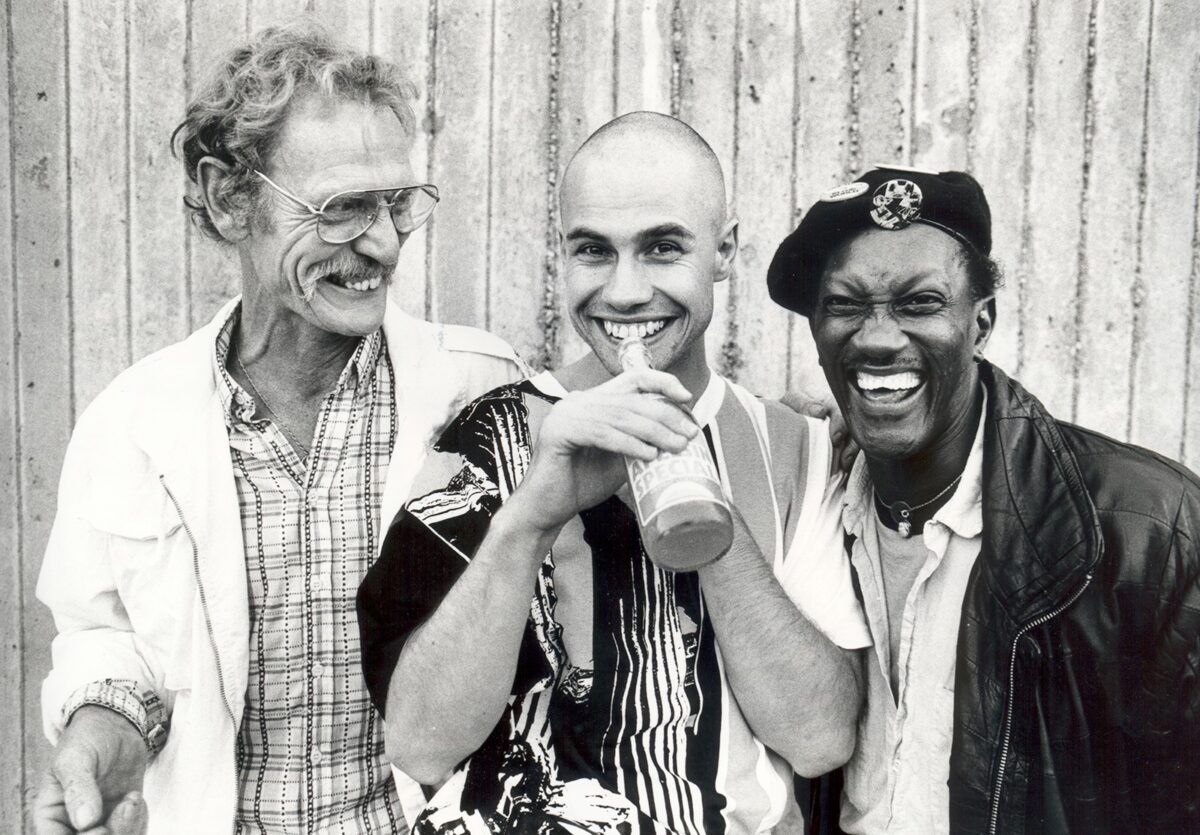

In the mid-80s, he had a trio with Cream drummer Ginger Baker and Parliament Funkadelic keyboardist Bernie Worrell. The group toured for two years and actually went into the recording studio following a festival appearance. However, the album was never released until late last year when Hellborg released it as The Concert of Europe. It sounds just as incredible as you can imagine.

Each of the players brought something unique to the group. “Bernie brought his classical mind rather than the funk,” Hellborg’s website explains. “Ginger brought the complexities of African drumming fused with Jazz. Hellborg brought the freedom to go in any direction without hesitation or adherence to conventional wisdom or expectation.”

The Concert of Europe begins with “The Moon Suite,” which sets the mood with its exploratory three movements over 14 minutes. The chemistry and interaction is intense and exciting as they build up the music together. It really feels like three equal masters finding the equilibrium of the moment. Hellborg’s playing is exquisite throughout, with some standouts like his take on McLaughlin’s “Zakir” and the frenetic groove of “Ashhark.”

The Concert of Europe begins with “The Moon Suite,” which sets the mood with its exploratory three movements over 14 minutes. The chemistry and interaction is intense and exciting as they build up the music together. It really feels like three equal masters finding the equilibrium of the moment. Hellborg’s playing is exquisite throughout, with some standouts like his take on McLaughlin’s “Zakir” and the frenetic groove of “Ashhark.”

I got a hold of the bass guru to pick his brain about the new album, what it was like to play with Baker and Worrell, his double-neck Wal bass, and more.

The Concert of Europe is available now on CD with plans for a vinyl release.

How did you start working with Ginger Baker and Bernie Worrell? I hate to use the word “supergroup,” but it’s hard not to say this is a trio of superpowers.

It is a wonderful coming together of very unique individuals, let’s call it. I met Bernie in 1985 when I made my first proper record in New York called Axis. He played keyboards on it. I connected with Ginger after we played on the Public Image, LTD album called Album. It was produced by Bill Laswell with Johnny Rotten. It had an eclectic lineup on it with Steve Vai, Ginger, and Tony Williams. I played bass, and Bill Laswell played bass.

I really liked the way Ginger played on it, so I got his phone number and contacted him. We just happened to get along very well and ended up playing together. I think it was 1986 already when that happened. We played together for four or five years with Bernie and some other people, also. There were lots of European tours. Ginger lived in Italy at the time. So we went up and down Italy and played in Germany a lot.

We never made a proper record of it, which is why it’s probably not well known. It was also right around the time that Bernie was playing with Talking Heads for Stop Making Sense. They were promoting that a lot.

Ginger was off the radar at the time. Nobody was very interested in playing with him in those days.

He had a rough reputation, though I know you said you got along with him just fine.

Yeah. He was a nice guy. He was… He liked to push things a bit and provoke people. But actually, he was very kind and very generous. And funny. He had a very dry sense of humor.

He did not tolerate stupidity very well, or insecurity. If people were insecure and said dumb things, he wouldn’t miss a beat in getting on their case. That could be discussed as nice or not nice and maybe he was going over the top sometimes.

I think the general population thinks of him as the rock drummer from Cream, but if you dig in even a little bit, you find out that he was super into jazz and African drumming. You’ve played with so many great drummers: Tony Williams, Billy Cobham, and Kenwood Dennard, to name a few. How was playing with Ginger like compared to other drummers?

Ginger was probably the most unconventional and the one you could communicate the most with. He would respond musically to everything you did. There was a constant back and forth of musical ideas. He never went on autopilot and stayed on a groove. He was always aware of what was happening, turning things upside down and inside out. It was very challenging and kept you on your toes.

That could be awesome but also taxing.

In this case, it was rewarding and a lot of fun. He was a very rewarding person to play with. As I said, there were no predictable patterns that would happen. He would always come up with something very different, unique, and musical.

Ginger had this incredibly solid hi-hat going all the time. That was the clock one could always rely on. So whatever strange beats might happen on top, it would always be in relation to that pulse. He would use the bass drums to play either with or against your bass lines, nudging to develop and expand whatever was played while he was driving a beat, supporting harmony or ornamenting melody. He was truly orchestral.

You really needed to get deep into where he was coming from and his way of looking at playing rhythms. He would play stuff that was hard to understand sometimes, so he wasn’t considered to be that great for some time. As you said, it’s very rooted in jazz and African drumming.

The more I thought about it, the more I felt you two would make a good rhythm section because you have a lot of worldly influences in your music, too.

Many of my playing influences have to do with India and that tradition and not so much African, but I do have a little bit of that. Before Ginger, I played with a percussionist named Reebop, who played for Traffic and the Stones. He was from Ghana. We worked together in the beginning of the ’80s, so I had to learn a lot of the African stuff from him, which prepared me for Ginger, possibly.

Ginger and I played with a lot of the same people like John McLaughlin and those kind of folks. We had a common history, although he was a little older than me.

Do you feel you were playing in the same circles as Bernie, too, or was he more out of left field for you?

I think that playing with me – if I can put it this way – allowed him to do things that he was not called to do in other situations because he was known as a funk player, but he had a classical background. He was very happy to explore other ways of playing. Also, playing with Ginger would open up other opportunities for him that he didn’t come across with the more funk-oriented scene.

Bernie was a man of big ears. He would take nothing for granted and immediately go with you if we decided not to play the prearranged version of something. Also, he would reinvent and transform; nothing would ever be played the same twice.

So common for both and fundamental to how we functioned as a musical group was this ever-present awareness and readiness to get sidetracked if some interesting idea presented itself.

I think we got along very well. As you can hear on that record, we explored a lot and went in all directions.

I wanted to ask about the actual recording setup. You’re all exploring so far, but it’s all locked in. Were you all in one room and making eye contact?

Yes, it was like that. We recorded at Marcus Music in London. It was one of the biggest recording studios in London at the time. I had some ideas to start with, but it could take any turn with the interaction and collective improvisation at the time.

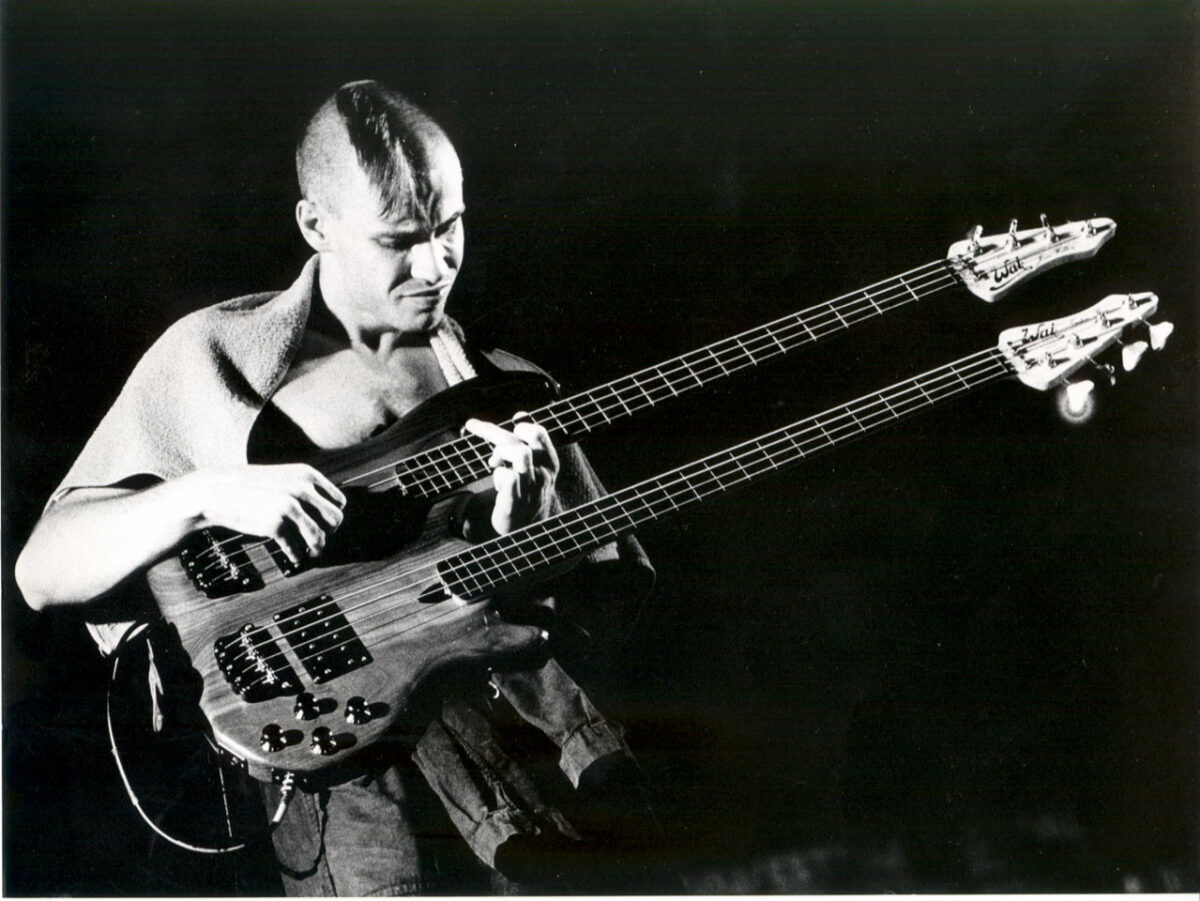

Were you using that awesome double-neck Wal?

Yes, I used that, and I also had a single-neck Wal with a Kahler Whammy bar.

One of the songs I got really pumped about was “Ashhark.” It’s so frenetic and totally slamming. Can you tell me about that tune?

Well, it’s been a long time since we recorded this, 35 years or something. Those were just the kind of jams we would get into. Ginger had this thing about moving one of the cymbals onto the floor tom. Instead of on the ride, he would play that, which gave this kind of garbage can sound.

Why didn’t this album show up for over 30 years? Did you always know you had this in your vault and didn’t find the right time to release it?

Yes. I have lots of recordings that I have never done anything with. At the time in the ’80s, everything was about the production. Everything had to be so perfectly packaged and produced. These were not songs in the conventional sense [that were] neatly put together.

At the time, I thought it was not a record. It was more of a concert or a live thing. I didn’t see it as something I could release. Also, everything was so… You made a record, then you had to make a tour and all of this. It was never solid enough with the availabilities of Bernie and Ginger to say, “Ok, we’re going to make this record and go tour.” It never came together.

A few years back, I listened to this again, and I really liked it. I guess it was time now to release it. That’s how it came about. I just felt it was due.

Do you have much more in your archives that you’re sifting through?

Well, I have a lot in the archives, but I’m not sifting through it. I did a lot of records, so I’m no longer feeling the need to produce many records. And it’s not a particularly lucrative business to be in anymore. I don’t think I’d make the money back to even mix and produce this record.

This album is only on CD, right? I didn’t see it streaming anywhere.

As for now, it’s only on CD. That’s a conscious decision. I’m not going to put it on any streaming, but I will put it on vinyl eventually.

I’m a big analog recording person. I don’t deal with computers more than necessary. I don’t record on computers. I have a very nice setup with about 15 all-analog recorders. Things you can’t find in professional recording studios anymore, you can find it here.

I don’t like CDs and the digital sound. There’s something to it that I can’t describe. I get high anxiety and a headache when I listen to digital music. When I listen to analog – particularly to tape – it’s just wonderful. It’s relaxing.

When I came to this realization about 20 years ago, when I had certain records on both vinyl and CD, I would line them up on the record player and CD player so they would play at the same time, and then I’d switch between them. The difference is so enormous. Even on “shitty” vinyl with low dynamic range and scratches and noises, it sounds so much better than CD.

Part of me assumed you like hi-fi digital music because, from my perspective, you value super clear, high-definition gear.

But it’s all discrete, all-analog stuff. I’ve never been into digital. I did some designs for Warwick with some preamps, but that’s because it’s what they wanted. I’m not into it at all. I like real amps. The heavy old stuff. But of course, hi-fi stuff that’s real hi-fi: analog stuff.

What else do you have going on?

One thing that I am working on is a record that is important. Since the early ’90s, I have been working with Indian percussionist Selvaganesh in different settings. Most notably in the groups that included Shawn Lane on guitar. But also various other ensembles. In parallel, we have also played as a duo. We had a plan for a duo record for a very long time and, in fact, did record tracks for such a release already ten years ago, but it did not feel quite right to me, so we recently made a new attempt.

For a long time, I have been interested in the music of the Indian subcontinent. My interest was never to try to imitate but to explore musical features we do not have in our tradition that can be valuable. One such field that has been discovered now by a lot of “Western” musicians is the complexity of rhythm, particularly of the South Indian (Carnatic) tradition. This has naturally been the foundation of my cooperation with Selvaganesh.

Another dimension of Indian music that I have explored but have felt quite alone in doing so is the field of tonality. The adoption of Indian tonalities (rags or scales is how Westerners commonly refer to them) has been limited almost exclusively to “modes” that resemble what we are already used to. My fascination is with what seems to a Western ear to be impossible tonalities. An example is one that is called Rag Shree in North India. In E, the simple explanation of the tonal content would be E, F, G#, A#, B, C, D#. If you would like to play music in the style of North Indian music, knowing these notes is far from enough. There is a world of information and knowledge that needs to be understood. That, however, is not my interest. To a degree, I explore to understand the parameters that would make such a different note grouping function as source material for music that would be relevant to me as a Western musician/listener. In doing so, I go to the source, the music played in India, but I also connect it with expressions that relate/connect with a Western ear/tradition/sound. There is an example of this tonality on my record Good People in Times of Evil.

On this new duo record with Selvaganesh, I explore other “unknown” tonalities and time signatures that are uncommon.

Relating back to the recording with Bernie and Ginger, there is a parallel rhythm. Ginger used what he called rhythmical gates a lot. In essence, creating a new tempo from an existing one, retaining the original “in the background. This could be exemplified, for instance, by generating triplets on a 4/4 beat and then subdividing the triplets into groups of 4 or 8 and treating that as a new tempo. This can, of course, be done with any tuplet and any sort of subdivision, creating great possibilities.

On Concert of Europe, part 3 of the Moon Suite is an example of this. I act as metronome in a way keeping a steady pulse while Ginger modulates in time and Bernie orchestrates the whole thing.