Disappearing Man: An Interview with Byron Isaacs

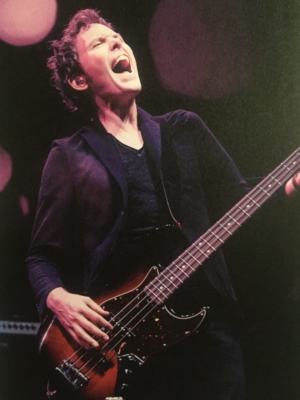

Over his career, Byron Isaacs has worked with some of the greatest songwriters of our time: Levon Helm, Willie Nelson, Joan Baez, Bruce Springsteen, Patti Scialfa, Roseanne Cash, and more. He co-founded the bands Ollabelle and Lost Leaders, plus he’s spent the past few years recording and touring the world with The Lumineers.

Suffice it to say, he’s been around the block. Isaacs may have just about done it all with a bass strapped around his neck, but now he’s ventured into new territory by releasing his debut solo album, Disappearing Man.

We caught up with him to get the scoop on his new record, his musical background, and the lessons he learned from Levon Helm.

I really dig the album. “Gypsy Wind” is really gorgeous.

Thank you, I’m really proud of that one. I love the bass clarinet on that.

Thank you, I’m really proud of that one. I love the bass clarinet on that.

That stuck out to me as a nice piece of arranging.

The player, John Ellis, pretty much improvised his whole arrangement on that. There was also a string thing that was arranged by John Lissauer, who worked with Leonard Cohen and a lot of great people over the years. So it’s a nice convergence of compositional arranging and improvisation. That’s what I like, anyway, and they came together on that track.

How did you get into music?

I grew up in Houston, Texas and when my parents split up I moved with my mom to Indiana. I was into the Beatles and The Who and the British Invasion stuff. Then I got briefly into Metallica because I liked the darkness and the power of that. Then a friend of mine, whose dad was a trombone player, listened to jazz. One day he gave me a cassette that had Charles Mingus’s Blues and Roots and on the other side Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus. They were two very different sounding records by the same artist and recorded within a year of each other. I vividly remember putting this cassette on and it was like the heavens opened up. It was like the hand of God reached down and grabbed me by the neck. My mom later told me that I said out loud, “This is like Metallica, but better!” [laughs] The raw power and visceral beauty of it [struck me]. That was it: I had to play jazz and I had to play bass.

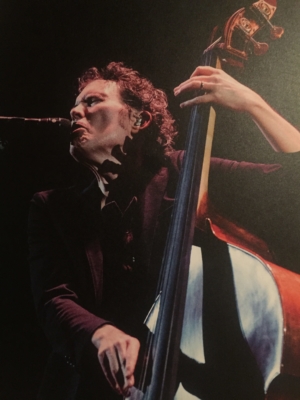

I had an electric bass and a little basement band that played the Beatles and The Who and stuff like that. The other guys were already into jazz, so they got me into the school jazz band where I started playing the upright bass. It was a new obsession. It never really let up. My career ended up veering me away from jazz after some years, but for about a good ten years or so, I was only a jazz musician. It took over my life at that point. I went to college and got to play all kinds of different jazz like the latin ensemble, a Brazilian band, fusion bands, and modern acoustic jazz stuff. I had to leave school to make money so I left and went to work on cruise ships. It was a whole other type of experience.

Were you playing in the show band?

Yes, and the show band would also do the dances. This was in 1991 and the old-timers at that point wanted to hear foxtrots and swing tunes. The dance sets were all jazz and you’d even get to take solos. If no one was dancing then I’d get to take a solo, too. Bass solos tend to make people sit down [laughs]. I also learned some things key things about dance music in that style, which is that walking bass lines make people leave the dance floor. If it’s a two-beat, you have to keep it a two beat. If you walk under a solo, people will sit down and not know why they sat down. It just starts to feel wrong. People will still enjoy it, but they’ll stop dancing. So you learn all the subtle power you have a bass player. That was a great experience to have at 19. Having to be in a dance band is an indispensable skill for a bass player.

Yes, and the show band would also do the dances. This was in 1991 and the old-timers at that point wanted to hear foxtrots and swing tunes. The dance sets were all jazz and you’d even get to take solos. If no one was dancing then I’d get to take a solo, too. Bass solos tend to make people sit down [laughs]. I also learned some things key things about dance music in that style, which is that walking bass lines make people leave the dance floor. If it’s a two-beat, you have to keep it a two beat. If you walk under a solo, people will sit down and not know why they sat down. It just starts to feel wrong. People will still enjoy it, but they’ll stop dancing. So you learn all the subtle power you have a bass player. That was a great experience to have at 19. Having to be in a dance band is an indispensable skill for a bass player.

I got to New York in the summer of 1994 to get into jazz, but what was happening with people my age in the scene at the time was a fad of people dressing up like it was 1940. People were so period about it that it was almost like chamber music. They were playing straight up bebop. As much as I loved bebop, I was more attracted to stuff that was later in the continuum. I found myself wanting to focus on more forward-looking music. If I brought an amp to a gig, I’d get so much flak. I got fed up with it and eventually found myself getting pulled into playing with singer-songwriters and rock bands. That scene at the time was flourishing and creative. Musically, it wasn’t boxed in at all. I felt I could express myself as a musician better in that context, much to my surprise. I continued to play jazz, but more and more I found myself getting interested in songwriting. I heard a Suzanne Vega album that I found so compelling. It was a singular vision, unlike anything I had ever heard before. It made me want to decode that and learn to write songs myself. All this is going on as I’m still identifying as a jazz musician. Slowly the desire to write songs creatively started to take over everything. Before long, I wasn’t playing much jazz. Songwriting became my world.

Did you feel conflicted about that at the time?

I felt conflicted about that for a long time, yes. There was a part of me that felt like I was betraying myself. Now I’ve made peace with that because that music lives inside of me. It informs every song that I write and every time that I play. I think about the way the energy of a song is moving in a way that is completely informed by the lineage of jazz. I don’t think at this point I could be called a jazz musician by any stretch, but every now and then I like to go play a jazz gig with friends. I’m always surprised to find that I still have something to say on the instrument. So I feel less conflicted than I used to.

What was the turning point from being a regular working musician in New York to working with artists like Levon Helm and Willie Nelson?

I think in a way there’s mystery woven into everybody’s story. One thing that I have noticed over the years is that, for everybody, the doors of opportunity are opening and closing all the time. It’s just whether you are ready willing and able to walk through that door. They will keep opening, but it will be something different every time. It’s funny how rarely those three things come together at once, but I’ve been fortunate that they’ve lined up for me at key places.

I think in a way there’s mystery woven into everybody’s story. One thing that I have noticed over the years is that, for everybody, the doors of opportunity are opening and closing all the time. It’s just whether you are ready willing and able to walk through that door. They will keep opening, but it will be something different every time. It’s funny how rarely those three things come together at once, but I’ve been fortunate that they’ve lined up for me at key places.

For any musician, it’s really important that you be ready. That’s the one thing that you have complete control over. You have to be on call with the skills. If you have your skills together, then the other things are a roll of the dice.

Early on I got to play in this rock band called Elysian Fields that I loved. They’re this beautiful art rock band that’s deeply jazz-influenced, but they’re doing songs and are kind of a rock band. At times it’s raucous and profane, so it’s all the things I love. The drummer in that band, George Javori, was about to go on tour with Joan Baez. It was a very different thing, but he said to me, “Dude, come with me on this tour. With the two of us together, it’s going to be awesome.” And it was. That was the first time I had played with somebody famous. Joan was great and musically adventurous. It turned out to be much more of a musically nourishing experience than I would have guessed. At first, I thought, “Well, I’ll get to be with George and play music and hang out a lot together.” It was a great band. Joan wanted it to be different every night and there were moments in the show where we were doing free improv. We kept it a Joan Baez concert, but it was conspicuously different from all her other tours and all the reviewers said as much. At that point, I got a little bit of name recognition.

Meanwhile back home, I was beginning Ollabelle. It was through that band, which had Levon Helm’s daughter in it, that I got to meet Levon. That was all an organic thing almost by accident. The keyboard player knew Amy from New Orleans and invited her in. I didn’t know who The Band was at that point. It was one of those holes in my musical learning. I hadn’t paid attention to music besides jazz for nearly ten years. So Levon came into the studio when we were doing our first record and he was a cool dude. He sat down at the drums and played a few songs. I thought, “Man, this guy’s groove is awesome!” Amy was just laughing while everyone else in the band was nervous. They were starstruck and I didn’t get it. So after the session, I said, “Ok guys, what albums by The Band should I get?” They told me the first two, so I got the Brown album. I remember putting that on and feeling like I did with Mingus with the heavens opening up. They sound so fresh and vibrant. That music really holds up. “Whispering Pines” makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up. So a few months later when I saw Levon again, that’s when I was starstruck [laughs].

That led to me playing with Levon. Ollabelle was the house band at Levon’s Rambles. We only left those when we put out our record and had to hit the road in earnest. Then he asked Jimmy Vivino to put a full-time band together for him. When Conan O’Brien got the Tonight Show, Jimmy and bassist Mike Merritt moved to L.A. and left the band. I had been subbing for Mike in Levon’s band when I was in town. Ollabelle had slowed down a bit and Levon called and asked me to join the band full time. I was in the band full time from then on until his death. I was a pallbearer at his funeral. It was an amazing time. I really wish I could have had more time with him.

I learned so much from Levon. His dedication to the music was relentless. It was so inspiring and so exhausting to try to keep up with. His concentration never lapsed when he was playing. It was very powerful and a spiritual thing, too. I quickly came to realize that playing next to Levon over the years that his concentration was like a steel trap. He heard everything. The more I paid attention to this, the more astounded I was. Maybe once a year, his concentration would break. It would just be some little wobble and I’d see him get furious. Then he’d redouble his effort and this power like a fireball would come out of that. I decided that I was going to match his dedication and intensity. He could sense that, and I remember him looking over and just smiling at me because he could feel my entering into the music with this new energy. From then on, it became like a game between us. It didn’t matter what he was looking off at – if my concentration lapsed, he would whip his head around at me and whack his cowbell [laughs]. He’d catch me every time. Every sour note by a horn player or any missed thing by anyone in the band, he’d catch it. I mourn him as a brother, as a father figure, and a wonderful human being, but mostly as my mentor. I miss him so much.

Getting back to the album, you mentioned you’ve been writing songs for a couple decades now. How did this album present itself to you? Is it music from the years or it came together recently?

I actually started this album ten years ago, but I’ve been busy with other bands that I was writing for like Ollabelle and Lost Leaders. It’s a lot easier to be in a band than it is to be solo. I kept pushing this album off partially because it was hard to look at in the face. I could slog through by myself on a solo album or I could continue to be productive in these collaborative areas.

I kept setting it aside until I was doing this Lumineers run. I was learning a lot about pushing music in a whole different kind of way. It takes a whole other level of mastery of projection of energy in that band. I was writing while I was on the road and started getting the itch to get this album out. It reignited my urge to get that done. I came off the road reinvigorated and with a lot of time because I let my other gigs go. I had a rare opportunity to do my solo album right so I jumped. It seems decades late and maybe a little weird for a 46-year-old dad to be putting out an album, but for me, it’s the perfect time to do it. I wanted to make some art that would land with people who appreciate it. I’ve been getting a lot of feedback from people who were moved by it, which was the intention all along.

What is the title, Disappearing Man, from?

There are a lot of reasons for that, from the internal struggles we have to the external struggles of the world at large. “Disappearing Man” has a better ring than “Disappearing Person”, and I put “man” just because I’m a man and it’s easier to personalize it. But I do mean the human condition on both a small scale and a large scale. New York is a big city that makes you feel small. If you’re an artist that comes here with no money and no prospects, then you can see how close to slipping into the cracks you are. You look around on the street and see people that really are falling through the cracks. It’s pretty terrifying. It’s pretty easy to actually disappear in a city like this. When I had kids, I had a whole other experience. Suddenly you have to change your priorities where you pretty quickly go from being number one in your life to not just number two, but maybe number three. The needs of the baby outweigh everything thing, plus the needs of my wife were essential. You necessarily have to de-prioritize yourself. That’s a hard period of adjustment. It’s enriching, but I know plenty of people in that position that go through an existential crisis. It’s the best thing for you, but it hurts at first.

Another aspect, which I hint at a bit in “Man of the Times”, is that there is now less and less need for manpower and even humanity itself. It seems we value money and corporations over human beings. We’ve decided that a corporation is a human, just one with fewer responsibilities than actual humans. They can’t go to jail or suffer humiliation. As a society, there’s a war on humanity. There’s a de-prioritization of humanity by us – by our own culture! It’s nuts. So all of these themes are parts of why it’s called “Disappearing Man.”

What kind of basses were you using on this?

Mainly I’m using my pride and jewel, which is a 1965 Fender P-Bass. It’s all original and immaculate. I’ve used it on pretty much every record I’ve made since I got it. It’s on the Lumineers record and everywhere. It was mostly that, but I also have a 1966 Guild Starfire II that’s black. On “Gypsy Wind”, that’s a combination of a Moog Voyager and a bass lap steel that I made. When I was getting into the whole Americana scene, I used to play a lot of slide on my old P-Bass. I’d detune it so I could play across the strings, but that became a hassle. While I was on tour with Ollabelle, I decided that I needed a dedicated instrument for it. I went to Home Depot and bought some wood. I kind of badly shaped a double-neck lap steel for a guitar neck and a bass neck. I tune the bass neck D-G-D-G. It’s got a Seymour Duncan 1951 P-Bass reissue single coil in it. The guitar neck has a Seymour Duncan Broadcaster reissue. It sounds fantastic and I use it whenever I can.

There are a couple places where I double the bass with a guitar or with a Danelectro six-string Tic-tac bass from 1964. It’s a copper colored thing with one lipstick tube pickup. It sounds so good and has a killer neck on it. So at times, I doubled the parts with that and a pick to layer that texture in there. Those are the main basses on the records, but I did use synth bass. “Losing You” has a Hofner President hollow body, which isn’t mine. It belongs to a great bass player named Jeff Hill. I recorded that song in a studio he shared with my producer, Hector Castillo. That bass just happened to be there. We weren’t planning on recording that day, but we decided to put a version of that song together. It came together just like that. It was the fastest little shot of inspiration.

What else do you have coming up this year?

I’m getting to be at home and being a dad, which is awesome. I’m focusing on my record plus I’m working on a record with my band Lost Leaders, also. I’m getting in a bunch of stuff before the fall when I get back into the studio with the Lumineers. Probably in the spring of next year, we’ll be back on the road. So I’ll get as much creative stuff done as I can before I hit the road with them again.