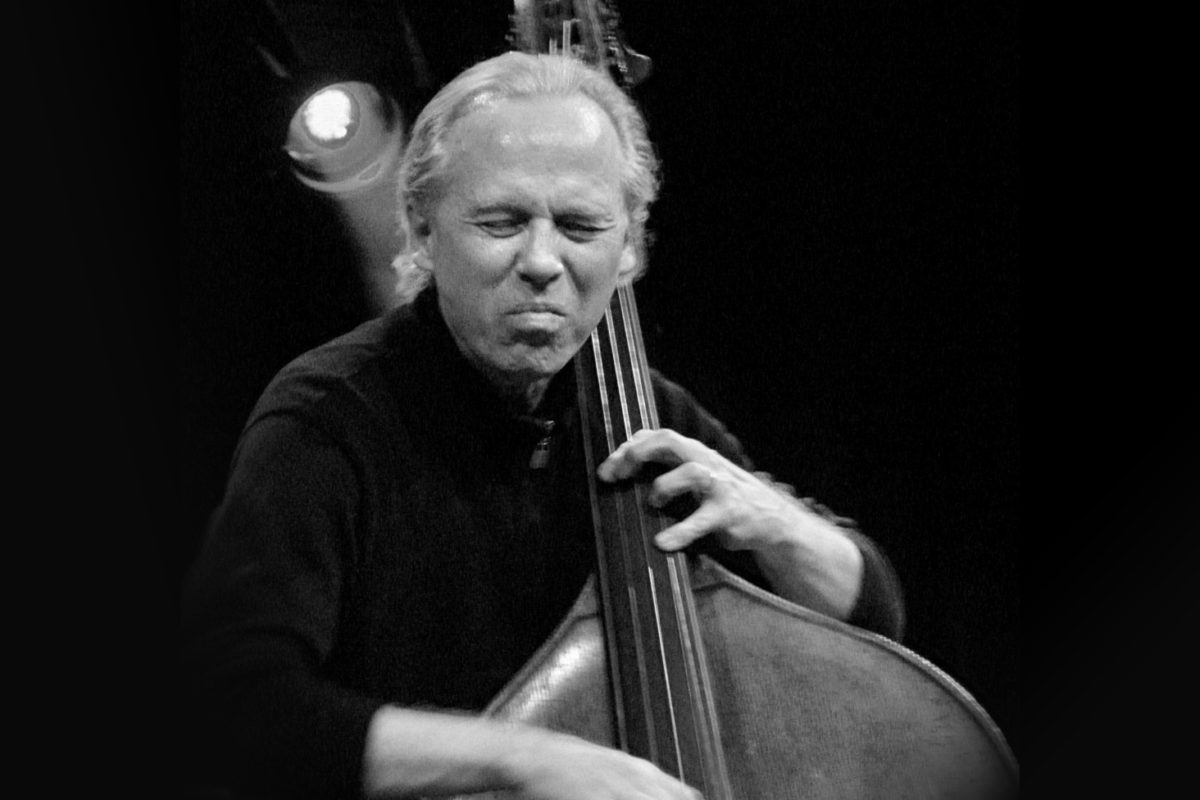

Overpass: An Interview with Marc Johnson

From his time in the Bill Evans trio to his Bass Desires quartet, to his work with his partner Eliane Elias, Marc Johnson’s career has been full of amazing music. His creative bass lines push any group he plays with, but his solos always present a deeply artistic experience. Now, the bassist has released his first-ever solo bass recording, entitled Overpass, on ECM Records.

On it, he explores textures, patterns, and rhythms across the eight-song collection, which draws on tunes from his illustrious career. That includes includes “Nardis”, which Evans used as a vehicle to feature the bass, as well as a reworked version of “Samurai Hee Haw” from Bass Desires. Every track is a revelation of the depth of what you can do with a bass.

We caught up with Johnson to get the scoop on Overpass, what he learned from working with Evans, and how he conceptualizes solo bass music.

Overpass is available August 27th on CD and as a digital download (iTunes and Amazon MP3).

You’ve played on tons of records, but this is your first solo bass recording. What led to its creation?

Several things. I’ve been experimenting with different ways of playing alone with the bass to make music and came up with a couple of different meditative-type, pattern-oriented concepts. That started the idea of doing a whole record like that some time. I’ve been experimenting with that and throwing them on different album projects for different people, like with John Abercrombie. There are some moments in a track here or there, where I dive into something like that, but I had never tried to do a whole piece from start to finish with just that being the impetus of thing.

Several things. I’ve been experimenting with different ways of playing alone with the bass to make music and came up with a couple of different meditative-type, pattern-oriented concepts. That started the idea of doing a whole record like that some time. I’ve been experimenting with that and throwing them on different album projects for different people, like with John Abercrombie. There are some moments in a track here or there, where I dive into something like that, but I had never tried to do a whole piece from start to finish with just that being the impetus of thing.

It started years ago with Bill Evans. He featured a solo bass moment every night on this tune called “Nardis”. I included that on the record as it was sort of a launching pad for this whole idea. That was in the late ’70s. I caught hold of Dave Holland’s album Emerald Tears around that same time and it flipped me out. It didn’t occur to me at that time in my mid-20s that somebody could record a whole album of just bass and have pieces and vehicles for improvisation just based on a particular little idea or another.

It intrigued me and over the years and the moment was right to just go in the studio. Eliane Elias, my partner in life and in music, was with me and her set of ears and musicality in the booth along with the engineer, Rodrigo, were a great help.

Anyway, that’s how it started. It was just a chance to go in and do some improvisations. I didn’t know it was going to lead to a whole album, actually. When push came to shove, there was enough material there. We edited it somewhat and then sent it over to Manfred Eicher, and he liked what he heard.

You recorded the album in 2018. Besides the pandemic, what made you hang on to the record before releasing it?

The process of getting it published usually takes a couple of years, anyway. Once you present it to Manfred, it takes a little while because he’s already got a plan for the next year or two ahead for his releases. He doesn’t release a lot of albums every year, so you’ve got to get in line. I also waited a little bit to see if I should release it myself because of this digital age we’re in or should I try to get it published by a label. Since I had a history with Manfred, I took it to him and he said, “Yes.” That’s how it happened.

When you’re writing and arranging for solo bass, you talk about conceptualizing ideas and drawing them out. Does that normally start from just a little pattern you come up with? I was just wondering how much you think about that before you’re jumping into creating these arrangements.

Mostly when I’m organizing material for a record, I think in terms of enough variation so it can hold the interest of the listener. It can’t be all pizzicato. I have some arco moments in there. I vary the density, too, by overdubbing on a couple of tracks so that you have this layered thing going on and more than one part playing at the same time.

On “Samurai Fly,” I did the two melody parts: one in one octave, one in the other octave, and then a pizz part to support the melody and give the harmony.

When [you’re making] a solo bass record it is pretty skeletal, and I did play off the open strings a bit just so it has this modal quality throughout for the most part. An exception might be the first tune “Freedom Jazz Dance,” which is a little more chromatic. I took quite a few liberties with that, but still, it’s on a Bb pedal and I keep that groove and that pedal idea going throughout the whole piece.

Rhythm is something I wanted to get documented, but I also [wanted to document] a different way of feeling pulse. Some of the more pattern-oriented things, for the most part, are in an odd time meter and so you get this feeling of an elliptical pulse instead. Unless you’re counting real small subdivisions. I like to feel like things can twirl and dance. If you’re keeping strict time – “one, two, one, two” – it’s going to feel at times like you’re on “two, one, two, one.” The emphasis shifts from one and three to two and four.

It’s more obvious if you’re listening on headphones and walking down the street, you know what I mean? You get the feeling it’s rocking from one side to the other side over the stretch of a two-bar phrase instead of just a quarter, heavy quarter note pulse.

I dig that aspect of this elliptical feeling and that’s why the last tune “Whirled Whorled World” comes to mind. You get that spinning, dancing effect and it’s not constrained. That’s the concept: you just get a pattern going and then it’s repeatable and then in the repetition of it, it becomes an identifiable motif. Once you play it enough times, then it has a regularity that the listener can identify, and then you can slowly morph from that or introduce another idea, juxtaposed to it, with the idea that you’re going to come back to it again later.

Then it becomes this piece and it just unfolds. It’s an improvisation with some intention behind it, but it’s not programmed. So when we get back to your question about how to set up your arrangements, it’s more conceptual and loose in that sense. You take an idea and then just run with it and see where it goes.

“Whorled Whirled World” struck me at times like Philip Glass and other times as a West African groove. How did that one come about?

In the late ’70s or early ’80s, I was checking out this Nonesuch album from their “Explorer” series. Somebody went to Burundi with a field recorder and recorded some of the musicians from their culture. There are a lot of different tracks on the record and one of them is this guy playing a really low-pitched instrument. He has several strings stretched across something like a hollowed-out log. It resonates deeply like a bass, but there’s no fretboard. It’s just these open strings that are tuned in different pitches. He strums them in different ways that create these patterns and pops and rhythms. That was conceptually where I was coming from when I got into that kind of meditative, pattern-oriented discourse.

Where did the album title come from?

The title and the cover art come from a piece called “Overpass” and it was painted by a friend of mine that I’ve known for years named Wade Carter. Wade and I go way back. We have a group of friends in common in Denton, Texas, from when we were growing up there in our teens into our early 20s. Wade and I didn’t really know each other very well then when we were living in Texas but he came to New York in the late ’70s when I was working with Bill Evans. We became pretty close friends then and have stayed in touch over the years.

Right around that time, in sometime around 2018 or 2019, maybe 2020, he sent me one of his pieces of art by a digital reproduction of it. It stuck in my head so when I was thinking about an album title and even the possibility for cover art, I remember that piece. We talked about it, I asked him if I could appropriate it for this project, and he said, “Yeah, sure.” [chuckles] We sent that idea over to Manfred Eicher and their art team and they dug it and they got behind it.

“Overpass” as a title worked for me on several levels. I didn’t mean for the record to be a retrospective look at my work over the years but in a kind of the way it is. When I looked at what the music was after the fact, I said, “Wow, I chose some music that spans my whole career.”

It touches on various signposts along the way. Like “Freedom Jazz Dance”, which was [on Miles Smiles], probably the first jazz album I ever bought. It was a gift for my father for Father’s Day, that summer of ’67 when I was 13 years old. I hadn’t started playing the bass yet; I was a mediocre cello player at that point. My brother’s name is Miles. I said, “Wow, look at this Miles, there’s a record here with your name on it. Let’s give that to dad for his gift.” I didn’t know Miles Davis or any of the guys in the band but we got it. I don’t know if my dad ever really listened to it. He was a musician, by the way. He passed about a year before this record was recorded.

So there you have it. “Freedom Jazz Dance” was on that Miles Smiles record. “Nardis” is a landmark tune we played with Bill Evans every night for a couple of years there when I was with him. Then “Samurai” is from Bass Desires, the first ECM record I recorded as a leader. You have a lot of history there personally speaking. It was really cool for me that I could include Wade, my friend, and collaborate with him in the publication of this.

It’s interesting that the retrospective aspect wasn’t intentional. When I listened to it I thought, “This is like a snapshot of Marc Johnson.”

It really is, and it wasn’t intentional. It wasn’t a conscious decision. It’s like, “Oh, it’s the subconscious talking here,” and maybe that’s how art is, especially in improvisational art.

Well, beautiful things happen that way. I would love to touch on Bill Evans and playing with him.

His 93rd birthday just passed on the 16th of August. I think of him often but especially when those days roll around. He meant a lot. I mean, what can I say? It meant everything to me to be able to play with him but had I never gotten the chance to play with Bill, just his influence, the music that he made, and the trios that he had, focused the direction for me.

I knew at a young age, once I decided to be a jazz bass player and pursue that, I would have gravitated to a piano trio format at some point or another in my development and career. Throughout my career, I’ve been playing in different trio settings, either with guitar or piano. Conceptually, Bill had a great deal to do with my development as a musician, as a bassist, and how I fit into different rhythm sections.

I wouldn’t have had that experience of knowing Bill so intimately as early as I did in life probably because of my father who was a jazz pianist and loved Bill. At a time in my life when I couldn’t really appreciate that level of musicianship, he was insistent that it was something that I should check out. Out of respect for my father and love for him, I got deeper into the music.

Bill is all through my life in one shape or form or another. It’s a spiritual connection that really galvanized and focused my path in life and in music.

What was working in his band like? What kind of lessons did you learn from him as a bandleader?

Bill was at a point in his life where – and maybe he always like this – he never rehearsed much. He felt like if you’re coming to play with him, you’re going to be on a certain level and the music is going to happen from the keyboard. If you’re not sensitive enough to dig that and be mature enough to hang with that, then you shouldn’t be there. He probably wouldn’t have hired a person that wasn’t right for the band’s chemistry. So I learned something about that. You look for players that you have an affinity to play with, and a lot of your problems will be solved without even having to talk about it.

He said some important things to me when I was that age – 25 years old and still pretty green around the years. Coming off the bandstand once, he said to me, “You know Marc, there’s one word that comes to mind that I think you should listen to. Play with more affirmation.” Affirmation is the word he used. I dug that a lot because I could tell from the recordings, especially the early ones, that I was reacting to what he was playing. I was maybe a millisecond behind him, just reacting instead of creating at the moment with him.

That’s a distinction that I didn’t become aware of until I had more confidence and more “affirmation.” I think that process for me was important and an interesting observation at that time in my life.

That trio was wonderful with Joe LaBarbera. Joe was like a big brother to me and really helped me a lot. He took care of a lot of business on the bandstand regarding time, and swing, and buoyancy, and just overall musicianship.

Without articulating in words, we were growing and the music was developing on its own in a very organic way. In those years, we had a lot of work. We were working constantly. We’d go into the Vanguard for a two-week run or we could go to Chicago for a two-week run. In those days, that was a lot. You could really develop a lot and on the bandstand doing two sets a night. Two weeks here, two weeks there consistently. The music did have this feeling of growth and spirit. I know for me, for sure, because I had so much to learn yet at that time. It was a great time.

Is there a specific time that you recall playing “Nardis” with them?

There were few times. Bill was listening to “Variations on a Theme by Paganini”, the Rachmaninoff piece. I could tell that his solos were developing a theme around that melody of “Nardis” but with incredible twists and turns and harmonic things that he was doing. I think the Paris concert in 1979, around that time in the fall of ’79, I became aware that his solo on “Nardis” was reaching an incredible level. So check out the live recording from the Paris concert from 1979.

There’s about to be a new release on George Klabin’s label called Resonance Records. He found a recording from Buenos Aires, which is about two months before the Paris recording. You can hear what Bill’s doing and well, the whole trio.

These solo piano moments to me are quite a departure from the vocabulary that you think of Bill Evans. Very introspective… something going on there is different. It’s really worth a listen.

That’s awesome. Speaking of that tune on your album, the last chord is stunning. Can you tell me what you’re doing there?

Well, I have an open G and an open E string. I’m playing the F sharp, just below the open G in first position. First position B on the A string. From the bottom up it is E, B, F#, G. I just slammed it and it resonated really nicely.

It just rings like a bell. It’s so striking. I had to listen to it a bunch of times.

I couldn’t hold that string down long enough to let it sustain anymore. If I could have, I would have. [laughs]

Do you feel like solo bass or soloing, in general, is the best way for you to express yourself?

I think anytime a musician is alone with their instrument, something different can happen. It’s a connection that you make, even if you’re just going to play one note and let it ring. You go deeper into the sound, into the space around the sound, into every aspect of the attack and the swell, the decay, where you pluck it on the string, down by the bridge, close at the end of the fingerboard or up higher in the middle of the fingerboard.

All these various colors become very interesting, and you can really focus on them when you’re alone. I wouldn’t say it’s in the practice room, but where else you’re going to be alone? By just playing the instrument and living with it in this way, you just discover different things. New ideas pop up into your head while you’re doing it.

I just love the bass. If you’re you’re attracted to the instrument anyway, you’re going to love just to hear a note ring or to feel this chamber of air moving and vibrating against your body. It’s just cool, but you’ve got to love it to get that esoterically into it. Anyway, that’s how it happens and one thing leads to another.