What Cha Got: An Interview with Bobby Vega

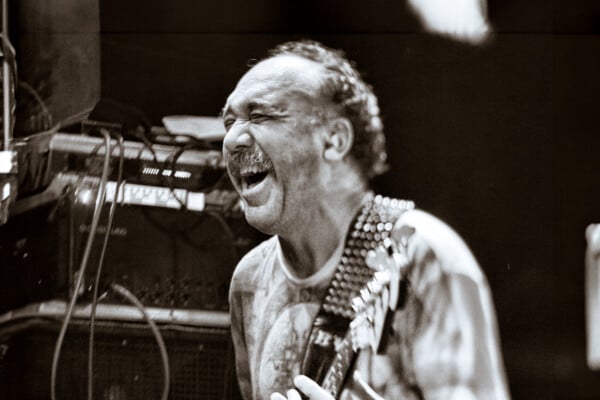

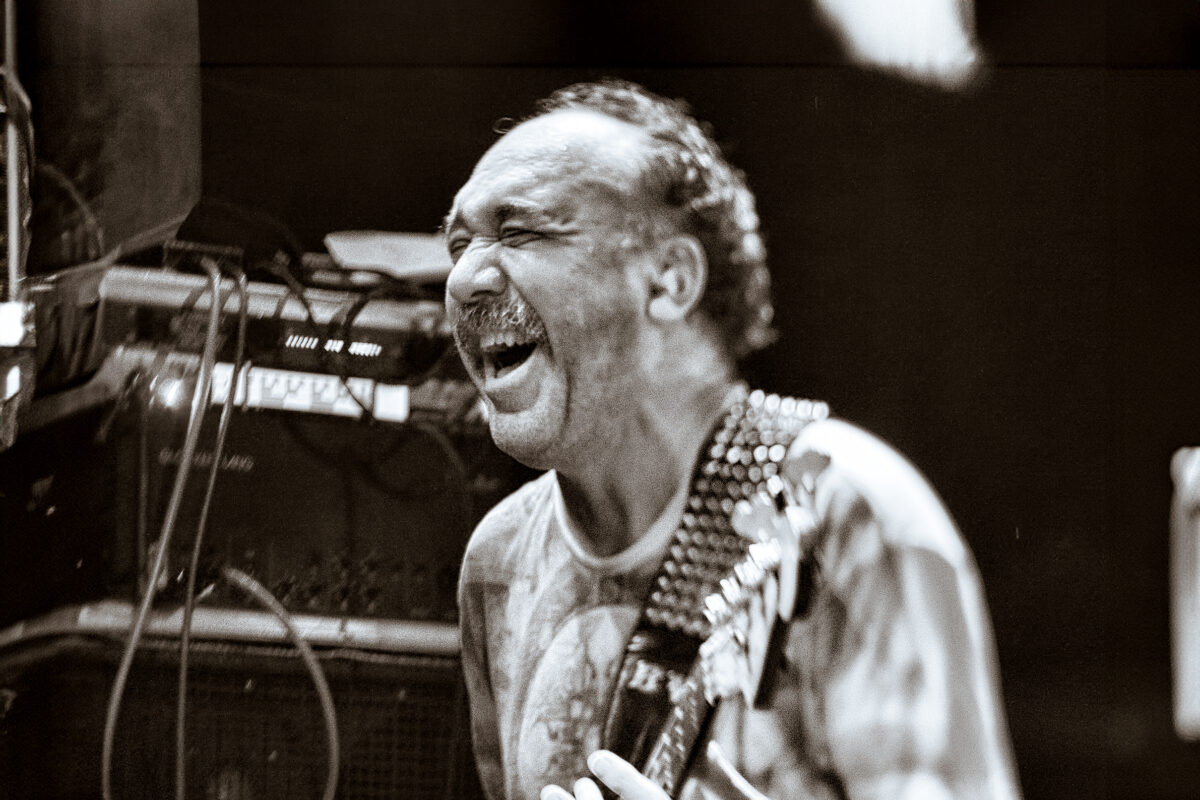

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, Bobby Vega was exposed to a wealth of music of every genre. He soaked it all in like a sponge while working at local venues, taking in the sounds and sights of now legendary acts.

After a gig with Bo Diddley, he soon became a staple of the scene at just 15 years old. From there, he’d play with Sly Stone, Etta James, Jefferson Starship, Lee Oskar, Jerry Garcia, Tower of Power, and many more. Needless to say, he’s got a lot of influences and experiences that helped to shape his unique and incredible playing.

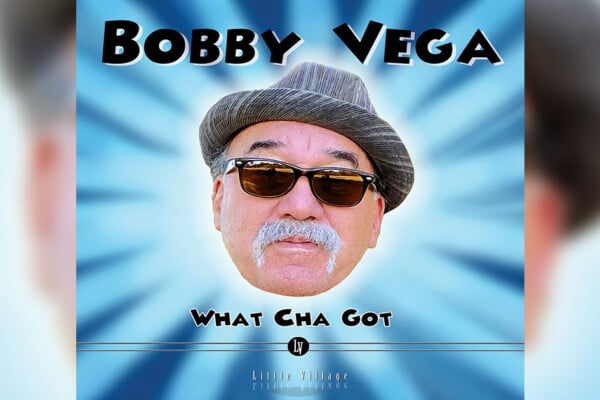

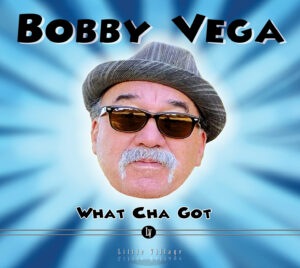

Vega’s latest album, What Cha Got, distills his singular musical personality into nine instrumental tracks. As you can expect, it is absolute ear candy that showcases his inimitable style and voice on the bass.

Vega’s latest album, What Cha Got, distills his singular musical personality into nine instrumental tracks. As you can expect, it is absolute ear candy that showcases his inimitable style and voice on the bass.

It starts with “Gush, Say Hey,” a fresh take on the song he played on a viral video for BassTheWorld. From there, Vega takes us for a ride on deep grooves, introspective melodies, and a little bit of chaos.

In this conversation, Vega gave us the low down on his new album, his take on playing guitar, his plans for helping bassists, and – of course – his glorious gear.

What Cha Got is now available for download through Bandcamp or streaming services.

I know your collection is like a timeline of bass equipment. Do you get to use all of it?

I have a room where I can set a lot of my stuff up. Not all of it, but a lot of it. Instead of having a treadmill, I’m going to have a couple of Acoustic 360’s, two flatback 8×10 cabs, all my Glockenklang rigs, my Hellborg rigs, Walter Woods, my Fender stuff, and my B-15… All this different gear where I can practice and play and discover new stuff on my own. If I was a dog, I’d be able to throw my own stick. There’s no master to throw the stick so I can make my own fun.

I’ve been gathering gear since I was 16 or 17, but it’s not a pissing contest. It just all has a certain sound that makes you happy and is fun to sit there and play and listen to. Not every bass sounds great through every amp, right? You have to pair them up like cooking or wine and dessert. That’s my passion because I love all the gear.

If it’s cooking, then you’ve got a big pantry. You’ve got all the ingredients.

Yeah. Through the decades, I didn’t buy a Ferrari or this or that. I got gear. I’ve been playing 60’s basses like my first stack pot I got in 1971, and it’s a ’61 Jazz Bass. I’ve been playing the Jazz Bass so long that P Basses were worth more than Jazz Basses when I got mine. I think the prices of Jazz Basses switched once Jaco came out, and then Larry Graham. It wasn’t John Paul Jones that made a Jazz Bass worth more money. I think it was Jaco and Larry Graham. Not that other people didn’t own them, but just as far as putting them up there in the spotlight. And nobody was playing the stack pot.

So anyway, that’s the whole thing. It’s like history. I’m just watching the decades go by and being, I don’t know, part of this music thing that I didn’t know I was part of. You don’t know what you’re doing or why you’re doing it. I didn’t even think about any of that stuff. I just love to play.

Your new album is just so good. It grooves so hard. How did it come about and what’s it all about?

It’s really about the insides of my life coming out of me. There’s all sorts of different grooves and styles on it. If I had tried to do this in the sixties, record companies would say, “No. You’re either rock or you’re soul or you’re country & western or you’re the blues.”

Nowadays people say, “Well, I play jazz” or “I play the blues” or “I play rock.” Mostly the jazz guys go, “Well, I play jazz. What do you play?” I say, “I play music,” and I might as well be the Grinch who stole Christmas. But it’s like, no, man: I play music. And after it’s done, someone else will name it.

The style, without trying to say anything, is the Bay Area. It’s my sound of the Bay Area. Is it funky? Is it rhythm and blues? Is it rock? Is it soul? Is it Americana? I don’t know. But that’s my insides.

So the CD is all these different things that are in me that I play.

There are a lot of different textures, too. I can hear your Ribbecke Bass on a few, and I’m assuming you’ve got the Shark Bass on there. What else did you use?

That’s mostly it. There’s three tracks with the Ribbecke: “Can’t Wait,” “Run With You,” and “Jellyfish.”

For the amplifiers I used the Glockenklang Bass Art top and an Acoustic Art cab. On the “Jellyfish,” I used the first year of the Ampeg amplifier. I don’t know what year it is. I think it’s a ’39 or something. It’s the first year before they even made amps, before flip tops. Then the Martin Ukulele.

But for basses, I mostly used the Shark Bass and the Ribbecke, except “Crackers and Chaos” is on a ’71 Jazz bass with black tape strings.

I wanted to pay homage to Larry Graham and played it with my thumb, so I was going to call it “Graham Crackers.” I did it with just bass and drums at first, then I sent it to Chris Rossbach, who works with Zigaboo Modeliste and is a good friend of mine. He laid the framework on the guitar and then I played guitar on it, too. After I played guitar on it, it got chaotic. That’s how it got to be “Crackers and Chaos.” I played some Steve Cropper stuff on it, then Chris finishes it off with a signature Rossbach guitar solo.

Now, if you listen to “Skunk Train,” that’s my stack pot Jazz bass and I’m playing with my thumb there, too, but that’s a whole different vibe. That song is about a friend of mine that had a gig for Lagunitas Brewing Company. There was a train down the block called the Skunk Train. They said, “Okay, come on and play.” The gig was for all these people that are on the train drinking Lagunitas, smoking dope and eating while we’re playing. So that’s me imitating getting on a train, going through the Redwoods in the park with everybody eating, drinking, and partying.

Have you played guitar on a lot of other projects? I don’t remember you talking about that before.

No, and I have guitars, but I just never had the balls to do it. I actually have a killing guitar and guitar amp stash. I’m playing guitar on “Say Hey,” “Skunk Train,” and “Crackers and Chaos.” I put that Freddie Stone-ish kind of thing on it and then the “Amos Moses” Jerry Reed-ish chicken picking. All that kind of influence.

When I’m playing guitar, it’s actually how I play the bass. It sits so much better with a bass because I’m playing counter bass parts. If you listen to a James Brown record, there’s a bass line and then there’s a second bass line, but the guitar’s playing the second bass line.

When I play guitar, I play more on [the back of the beat] than on top. My bass playing is usually in the front, going forward and the guitar part is holding it back more, just trying to lay it in the cut. If you hear the “Skunk Train” bass by itself, you go, “What?” But when you hear the guitar accompaniment that I did to it, it goes through all the different gear shifts and emotions and it builds just right.

Even though it’s all instrumental, it seems like all the songs have a backstory to them.

There are so many different things on the album that are part of my life of memories.

“Helicopters” is a song that I wrote for [legendary concert promotor] Bill Graham. The last time I saw Bill Graham, it was a New Year’s show and he came up to me in the dressing room and he goes, “Hey Bob, you know what’s going on?” I said, “I’m working with Etta James.” He goes, “Oh, that’s cool. What else you doing?” I said, “I’m working on this solo project.” And he says, “Well, you know what? It’s about time you steal second.”

Since it was New Year’s, he had a bunch of different shows going on in the Bay Area and he would use a helicopter to go do the books and the tallies. He would fly from Concord into Sacramento and to San Francisco, wherever that he had a gig at. [When he died], I was just really sad because if it wasn’t for Bill Graham, I probably wouldn’t be playing.

At a certain time I got to go to the Carousel Ballroom, which was the Fillmore on Market Street. I’d go there on Friday nights and then Saturday I used to scrub the floors at the Family Dog to get in. I’d see soundcheck and then I’d come to the gig. I got to see bands play with all these instruments and then I’d go to music stores and all the hock shops when I was a kid. That’s what bit me. I quit school when I was 15 and I started working at Don Wehr’s Music City. So that’s where it all started.

And then the last song on the thing is called “Happy You, Happy Me,” and I played ukulele. Kid Anderson played the upright bass, Jimmy Pugh played the organ and Prairie Prince played drums and then the little clave. And that’s it, because like song goes, if you’re happy, I’m happy. That was the first song that I recorded on the CD. I did the last song first.

I really love the way that wraps up the album. It’s a happy little island vibe.

Before [my son] Rocco was born, I went to a hock shop in Santa Rosa and there was this Martin Ukulele for 250 bucks and it had gut strings on it. And I said, “I’m gonna buy that and I’m gonna play ‘Hey Good Looking’ for my kid when he’s born.”

I’ve had that song for a long time. A lot of this stuff is… you know, people call it these grooves and noodles, but as soon as I play guitar on them, they’re not noodles. It’s music [even if] they can’t hear what goes around it. Some people might think this stuff isn’t finished. Well, guess what? It’s instrumental music. There’s room for your brain to participate. Put on some headphones, go outside with it and tell me what you see. Now the music will start taking shape because now there’s a visual there, whether it’s the beach or it’s downtown where you’re seeing homeless people, or anything.

Listen to “Kimmie.” That’s about my girlfriend. She used to go down to Cabo she would bring car parts, tennis shoes, candy, and all kinds of other stuff for the people that would ask for stuff. They’d say “What Cha Got?”, and the main riff emulates that phrase. And then all that other part is like going through the neighborhoods down there.

That one in particular seems like an epic story told in music.

What I was going for there was more of the 50s and 60s, like that Cal Tjader song “Wachi Wara.” Then I put “Rock & Roll Hoochie Koo” on the thing. That’s all the shit that’s all inside of me. I saw Johnny Winter play that at the Carousel Ballroom at the Fillmore. And then you see Santana and what’s the most cliche line that happens every time? It’s [the progression from] “Walk, Don’t Run,” and now you got the extension. Then you add all that tension – you know, the James Bond shit.

So these are all the kind of things I’m talking about. It’s like what Jaco goes said – I can show you where I got everything from, whether you believe it or not. These are my influences. I don’t sound like anybody; I sound like everybody. Because I grew up listening to everything and everybody.

I’ve worked with Joan Baez to Etta James to Babtunde Olatunji to Sly Stone to Santana to Jerry Garcia to Jefferson Wheelchair to Cold Blood to Tower of Power. What am I supposed to sound like?! Talk about confusing. And this is the same way as my race. I’m 15 things. I spit in the cup for Ancestry and I think I’m 17 things now. You know what I am? I’m a person and I’m American.

I began to realize something when I started to go to Germany and Japan and to Italy and to England and Canada. You know what happens? I play like an American. Not all Americans, but this is where I learned it from.

We play our experiences, so there were different things that I learned. When I got gigs, I didn’t know how to play those gigs or those styles. I played with Paul Butterfield and I didn’t know how to play the blues when I played with Paul Butterfield. After the gig was over, I had a grasp on it and it became part of my DNA.

And I just love to play. Back in the day, I just sat home and played for eight hours or whatever every day. Whether I smoke pot or not, or ate sandwiches. When I first started playing at like 16 or 17 in my apartment, I’d have the TV on and I’d have the stereo on and I’d be practicing. Just playing, playing, playing, playing, playing, playing with the TV and the radio on while I’m playing. Now it’s better when everything’s quiet.

Yeah, so that’s the short version of the too long story. Now I get to go enjoy it because all of that gear sounds different with all the different instruments that I have. So now I’m just pairing them up. I know the difference between an 8×10 flat back and the newer 8×10 cabinets. I know what amps to use and whether they’re not going to change the sound, just to get the amplifier to manipulate the guitar to accent me, to get me to play in other ways.

I’ve been screwing around with the fretless. I’ve got four or five or six, and they all sound different and they inspire me to play different ways. It’s almost like playing cello or having a saxophone.

You get that extra expression from it, right?

Well, you get that really with your hands, too, depending on their position. I have a Music Man fretless that I just got – I think it’s a ’95 – and it has flats. And man, that thing sounds great. So it makes you play different, though.

I have a ’77 Jazz bass with a three bolt maple neck and I use round rounds on that. That’s really a Jaco-ish sounding bass. That with a set of Swing Bass 66 on it… Ooooh, it’s like conjuring up the ghost of Mr. Chicken.

Then I have an MTD that Michael [Tobias] made and called the Marilyn. It has an African mahogany back, redwood burl top that’s chambered, ebony fingerboard, titanium truss rod with a piezo bridge and two Bartolini’s… the black tape strings. That thing has a voice.

As far as playing, there’s how much downward pressure [with your left hand] you want and then there’s the pick and then fingers, whatever you want to do. You have this whole palette.

The trick – that’s not a trick – is to be able to use a pick or your fingers or your thumb and that when you go to use them they all are the same volume. You can make them stick out or hide them, but they’re all the same.

When people go, “Man, when I play with my thumb, it’s out of balance with my fingers.” Well, why is that? Because it is out of balance. So who’s going to fix it? You.

I believe that we’re an instrument, your guitar is an instrument and your amplifier is an instrument. If you’ve line all those up, now you’re playing with power.

That’s what I would like to do to help people. Instead of calling it a lesson, we would have to figure out a price plan and then you can have 15 minutes, a half hour, or whatever it is. We’ll talk about gear, let me help you shop, figure out whatever strings, amps, whatever.

Or you tell me who are you trying to play like? Well then I could say, “Here, get this kind of chorus pedal,” if that’s what it is. Which reverb do you buy? Which delay? Well, let me help you out if that’s what you want. Here, let me show you some tricks and what you can do with that. Here, check this out. Okay, now you go mess with it. You go have fun.

If I look at how long it took for me to observe and absorb this stuff, it would be like if I tried to hardboil an an egg by holding it up to a light bulb. I want to help people so it won’t take them that long to get to where they’re trying to go. I think talking sometimes is better than playing and then you can get to the playing part, too.

You have all the history of the bass stuff really down. Are there any new trends or things happening in the bass world, either with gear or with players that you’re excited about?

Not really. I’m more excited about listening to music or trying to figure out stuff just to have some fun. I hope everybody realizes that it’s their turn to have fun!

I ain’t trying to be the next Jaco or the next Victor Wooten or whoever. God bless whoever’s playing music now and making a living at it because man, that’s tough.

For me, it’s “can you make the band sound good?” I learned how to play by accompanying other people so they can tell their stories, whether it was singing, somebody soloing, whatever that was.

One time when I played with Tower of Power, Rocco said, “Hey man, this gig’s gonna be good for you.” I go, “What? I can’t play like you.” He goes, “I [expletive] can’t play like you either.” And that was freeing because that let me know that I could play how I play, even though I was playing through his spirit.

Back to the album for a second, how much have these songs stayed the same and how much have they stayed the same over the years?

Did you ever listen to Marcus Miller when he was with the Jamaica Boys? Then you hear him play with Miles on Tutu. Then The Sun Don’t Lie comes out. If you listen to the Jamaica Boys and all his earlier stuff, you’ll hear all these ideas and now they’re developed and applied in music. That’s what What Cha Got is.

My first record I did was called Down the Road, and I used the Turtle Island String Quartet and Airto. The reason why I did that is because Victor Wooten and Victor Bailey were out and they were going boogity boogity bank bank and I didn’t want to go boogity boogity bank bank because I thought that they were already doing it. Even though I do it different, I went the other way.

So now I just went, “Well, What Cha Got?” And this is what I got. I think it sounds like how I play now. I’m not saying that it’s great or good, but this is how I sound.