Read Up! Part 2: How to Find and Work Through Books for Bass

Ah ha! You’ve reached the oh-so-exciting section of the music store where the possibilities seem endless and you get giddy just thinking about picking something up and taking it home… No, not the bass wall… the bookshelves! You feast your eyes on the “Teach Yourself Harmonica” manuals, the transcription books of Green Day guitar solos, and, everyone’s favorite, the 100 Greatest Showtunes Realbook, and you think “if only I had the money….” Ok, so maybe I’m the only one that does that, but in all seriousness, it actually can be empowering to think about what you could learn in all of those books. At the same time, attempting to sort through the stacks to find something appropriate for you may seem like a daunting task, especially if you don’t have a good track record with working through books that you’ve bought in the past.

Despite my love of literature, finding the motivation to work through a music book isn’t easy. As someone who primarily learns by ear, and who spent the first few years of playing bass without reading music, I had to learn how to work from a book and which books were best for me. This process involved concentration, a huge amount of self-discipline, and a lot of trial and error. Books certainly can test your patience, but they can also act as great tools for learning your instrument. Whether you want to focus on new techniques, study a certain player’s approach, or learn the basics of a new genre, working through a book can be a great addition to your practice regiment. Here are a few suggestions for finding a book that’s catered to your learning needs and some ways to start working through it (and stay motivated once you’ve started).

If you find yourself perusing through the books, attempting to find something new to take home, here’s what you should keep in mind:

- Be inspired to take it home and start working immediately. If you get excited about it, you’ll go home, put it on your music stand, and turn to the first page. If you buy it thinking that it will look good on your shelf, then that’s probably where it will stay.

- Make sure it’s appropriate given your current ability. If you’re a beginner, working through Victor Wooten’s transcription books may be a great thing to aspire to, but it will probably give you more frustration than inspiration. You want the book to provide you with a challenge that is within your reach. The exercises should be difficult, so that you do have to work through it, but you should also be able to make visible progress.

- Think about other players’ recommendations. Have a friend, teacher, or store employee give you some advice and find out why it’s a valuable practice tool. Then, think about whether or not it will be the right choice for you. With all of the books out there, it’s good to have some direction when you search for one, but make sure it sounds like something you’ll benefit from and be willing to tackle.

Once you’ve picked out a book, it’s time to start working… and then keep it up. When it comes to motivation, there’s nothing better than regular private lessons. Not only will you be assigned certain exercises based upon your skill level, but your progress will be monitored, you’ll get suggestions on how to improve, and you’ll have a deadline. There’s no real substitute for that kind of accountability.

If you’re not studying with a teacher but want to work through a book on your own, here are a couple of ideas to help you get the most out of your practicing.

- Start slowly and work your way up. Most books follow this logical progression, especially if they’re technique or genre based, but there are a few out there that don’t follow this rule. If you’re new to reading, work on easy exercises at first and allow yourself to get comfortable with this type of practice. For example, Standing In The Shadows of Motown is a great book with some amazing transcriptions, but if you’re not used to reading in flat keys or deciphering complicated rhythms, it can prove to be extremely difficult. Start by paging through and finding the shorter excerpts, work through them and get familiar with the style, and then try tackling “What’s Going On.”

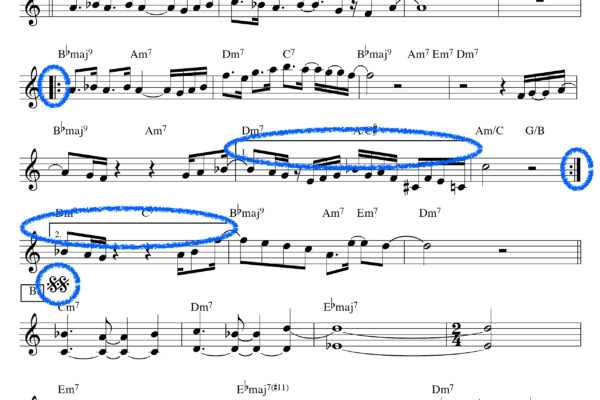

- Set small, achievable goals. If you’re working on a piece of music, whether it’s a Bach cello suite for bass, a long walking bass exercise, or an artist’s transcription, it’s important to work through it strategically. Your practice method may be a bit different if you’re trying to read and memorize, as opposed to just read, but either way will require breaking the piece into small sections. Try working on 4, 8, or 16 bar phrases (depending upon the difficulty of the piece), and make sure you review previous sections. That way you’ll be able to self-motivate by achieving these small goals on a daily basis and you’ll ultimately make it through the whole piece.

- Identify your “trouble sections” and give them more attention. Although this may seem obvious, many people play through a piece from start to finish and continue to stumble at the same places. Clearly, this isn’t an effective way of practicing. Instead, take the trouble section, break it down so that you can find the best technical way of playing it, slow it down and work with a metronome, and then reinforce it by playing the section multiple times. Then integrate it by playing a few bars leading into the phrase and following it out. This will give the phrase context and you’ll develop a fluid way of playing up to and past the trouble section.

- Give yourself a deadline. Although you may not have a teacher pressuring you to finish your piece by next Wednesday, you can still circle a date on your calendar and hold yourself accountable for your progress. You can have small weekly deadlines, such as “Work through page 12 by Friday” if you’re going through a book, or “Track #3 by Jan. 18th” if it’s a specific piece. Then, set small goals designed to help you meet the deadline.

And finally, whether you’re picking out a new book or finding a better way to play through the ones you already have, make sure you remember what you’re working on. If you’re trying to improve your reading, don’t get frustrated, give up, and play the CD. If you’re focusing on technique, keep an eye on your hands and make sure you’re not developing or reinforcing bad habits. Finding the right book can make a huge difference in your playing and overall musicianship. The key is to be inspired by what you’re working on and to benefit from the time and effort you put in.

What are you reading that’s helped you/inspired you/given you a new skill? Tell us about it in the comments!

Photo by Herman Brinkman

Ryan Madora is a professional bass player, author, and educator living in Nashville, TN. In addition to touring and session work, she teaches private lessons and masterclasses to students of all levels. Visit her website to learn more!

All excellent advice. I take a somewhat different approach though. Admittedly I only take one regular pupil; I haven’t the time or the inclination for more. I’m too busy playing; and I got tired of pupils who wanted to play, but didn’t want to put in the practice time. For my pupil I set regular exercises, scales, arpeggios, cycle of fifths, key changes etc; but we “write our own book” as we (she) progresses. This “book” is written by discussion and mutual consent. My lessons are not particularly structured before the pupil (an incredibly enthusiastic woman), arrives. We play through previous “homework”; all of which has been hand-written on manuscript paper during our lessons. Every week my pupil shows huge improvement; because she practises (“practises” is correct in UK and Australian English!) with such enthusiasm and dedication. After our session working through the previous “homework” we sit down and discuss what we both think will be most advantageous for her next. This could be writing a quick “mud map” chart for a particular song; (the sort of thing she’d be likely to face in a real gig situation); to a properly notated full-blown chart; depending on the difficulty of the piece, and how accurate she actually wants to be. Obviously as the weeks and months go by; the “book” gets bigger; but it’s full of material she can look at and refer back to if needed. It becomes her own “Bible” if you like, without wishing to sound pretentious; but there’s nothing in there she doesn’t understand. Just to keep this response short (it’s already far too long!); I’ve watched her go from being a wannabe who’d never played in public, to someone who jumps up and plays with very respected musicians on a regular basis; with confidence and a smile on her face. The people she’s now playing with also respect her of course. They know she’s a “beginner”, but her enthusiasm and joy spread to the others; who also enjoy testing her abilities in a firm but nurturing manner. Everyone wins. Especially me; because I reap the reward of the “lessons”, and she’s on stage playing. There’s a lot to be said for writing your own book; as long as you understand what’s in it! Hope this makes sense.

Interesting piece Chris. Having taken up two new instruments at advanced age, the prospect of going back to lessons with a teacher filled me with dread, but it’s turned out well. As to be expected, you sound like the perfect mentor.