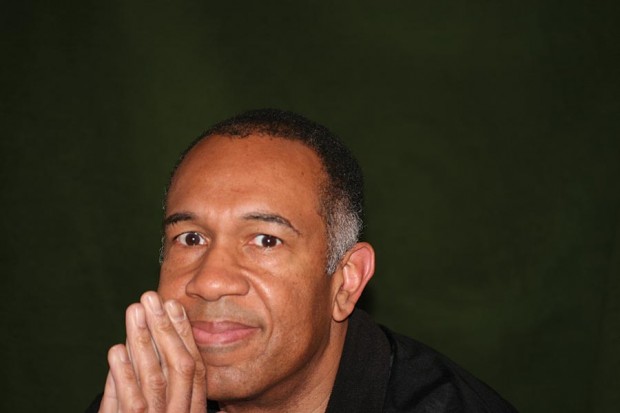

Brotherly Love: An Interview with John Clayton

Few names are as ubiquitous in the jazz community as John Clayton. As a prominent bassist, arranger, and composer, Clayton’s incredible musicianship has kept him busy since he was a teen with artists like Henry Mancini, Quincy Jones, Queen Latifah, DeeDee Bridgwater, and Dr. John, just to name a few. Most recently he collaborated with Paul McCartney for Macca’s Kisses on the Bottom album and Live Kisses DVD.

He’s also an experienced band leader with The Clayton/Hamilton Orchestra and The Clayton Brothers Band. Featuring brother Jeff on sax and son Gerald on piano, the Clayton Brothers have just released The Gathering on the crowdfunding label ArtistShare.

A pupil of bass legend Ray Brown, Clayton’s commitment to bass is evident in his playing as well as his dedication to education. He often teaches workshops, but has been offering free bass tips on his website for general guidance.

We reached the bassist at his home studio in Los Angeles to ask about the new Clayton Brothers album, arranging, working with Paul McCartney, bass education, and studying with Ray Brown.

You just got off a mini tour with your band, The Clayton Brothers. How did it go?

Great! We had a lot of support, and it’s really fun to play with this group. I don’t have to think, you know? I don’t have to adjust. Everybody knows what everybody else kind of likes and we kind of push each other along and inspire [each other]. It’s not business as usual, but there are so many basic things you don’t have to think about.

How often do you use a bass from the area you’re traveling to?

Never. I tried that, but it doesn’t work. The kind of stuff we do requires that you have your own instrument; not just a decent instrument. I can get my hands on a decent instrument, but strings are going different, the setup is going to be different – the strings might be closer to the fingerboard or the might be further from the fingerboard – and next thing you know you can’t get a sound or you’re killing yourself to play it. Now we’re talking physically when you’re plucking those strings… it gets bloody. [laughs] Literally. So I kind of want my own instrument.

How do you set your action?

I keep it high enough to keep the instrument happy. In other words, if the strings are too high off the fingerboard it chokes off the sound. If the strings are too close to the fingerboard, you don’t get a sound. I can adjust, so there’s not like a certain millimeter that I look for from the string to the fingerboard, I mainly just go for whatever is going to allow [the instrument to sound].

And I try to make sure it’s playable. My criteria is that if I take the bow and try to play forte with the bow and make it really full, when I push down with the bow, if the string touches the fingerboard then the strings are too low. So then I’ll raise it up to just beyond that point.

So you just released The Gathering with the Clayton Brothers. What brought that about?

Well it was kind of my brother’s idea. He wanted to do something that would allow us to basically gather: gather friends, gather music, and the gathering of friends meant in a sense that we were gathering a new sound, if you will. And that was really it. That was the vibe, just kind of like, “What can we do that will be fun for us and also give us a new sound?”

Obviously it’s a family affair, which got me thinking about how that fosters musicianship. I assume you had a lot of music in the household growing up?

Yeah, but not a lot of jazz. My mother played piano and organ in church and sang in the choir. So we always had music in the house with her practicing and rehearsing with groups. Then we listened to the radio, but we were listening to our pop music of time, which was rhythm and blues and soul music. Stevie Wonder, The Temptations, The Four Tops, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Ray Charles… That’s what we were listening to. Then my brother and I got into the high school jazz band and that just opened up our heads.

How does family play into that, especially with your son’s musicianship? How do you see that role?

You know the whole family thing was almost accidental. My brother and I, we didn’t have a group. We were just playing music separately and together, but less together than when we were adults. As kids, we just did all the kid stuff: playing in the high school bands and in our own little bands. He’d have his little bands and I’d have my little bands. We played in church occasionally. My mom allowed me to play in Church as often as I wanted, but she didn’t allow my brother in the beginning to play that “heathen” saxophone in church. [laughs] He ended up singing in the choir and eventually she turned her thoughts around and he was able to play sax in church.

But that was really it. As for the family thing, like with Gerald… my brother and I put together [The Clayton Brothers] in the ’70s and recorded then. After Gerald was born, of course he grew up at our side watching and listening and all that. When he started playing piano and progressed, I had a couple of little gigs for him and said, “Hey, want to play with us here?”, and he did. When he was graduating from college I said, “You know, of course we’d love to have you in the Clayton Brothers more permanently, but it’s totally your decision. If you want to go your own way and all that, [I understand].” I didn’t want to pressure him to play in “dad’s group.” He’s got his own ideas, but he said, “Actually, luckily for me it’s been my dream to play in The Clayton Brothers group.” So that was a really nice thing to hear.

That must have been a good feeling.

Yeah, especially since I wanted his voice there. So that’s kind of how all that happened. It all just sort of naturally flowed.

You’ve been going through ArtistShare for your last few albums. Do you see crowdfunding as the way the industry is going, or did you just want to give fans the experience it offers?

I think in the jazz world, it’s heading more and more like that. I like it, because it gives you a chance to develop a relationship with the people who are interested in what you do. With the other model we got used to, you’d walk into a record store – remember those things? [laughs] You’d walk in and you’d kind of browse through CDs that look interesting. That’s gone. You can’t do that anymore. So when [someone] puts out a new CD, there’s no way I’m going to know it exists because I can’t go browse in a record store anymore.

Now there are just so many hundreds of thousands of choices online that I have to look through to discover somebody’s CD. That ain’t gonna happen either. Radio stations are a really great way to discovers sounds I want to find, too, but that’s still limited. I’m not going to be able to find the fly-under-the-radar people. The other thing about the old model is that when I would by your CD, I’d pay for it – whether online or in a store – and I would take it home and enjoy it and you would never know that I existed. You would just hopefully get your royalty from the sales and that would be it.

With this other model, that’s gone. Now, if somebody in Kentucky is interested in what I’m doing, I now have their contact information. I can send them a thank you note. I can let them know that I’m actually going to be playing in Louisville and hopefully we can meet. Not only are you developing your relationship with people who like what you do, but you’re also creating this community atmosphere where since I’m in touch with you I can build this community. I can let you know what I’m doing and you’re not paying anymore for a CD. You’re paying for a chance to be part of the whole artistic process, which I find really cool.

Can you imagine if more artists were doing this? If you could follow along with Herbie Hancock or Wayne Shorter in the beginning and see what songs they’re thinking of doing on their next project and how their songs are evolving, or maybe peek in on one of Herbie Hancock’s rehearsals. You know, I think everyone would jump at that chance. That’s the goal of what we’re doing with ArtistShare. It lets people really be a part of the whole process, not just get a CD at the end of the day. They get to watch it unfold.

Do you think you’ll ever step away from that platform?

Well, another reason I don’t want to is because I own my music. When you record for Concord or Verve or Blue Note or whatever, you don’t own your music. They pay for the recording, sure. They pay for the musicians, they pay to have it pressed, they pay for advertising and all that stuff. But then they say, “You’re not going to get any money until we recoup our expenses, and then we’re going to pay you a royalty of less than ten percent.” So less than ten percent of your work, of your blood sweat and tears, of your sales… that’s what you’re going to get after [they] recoup all the money that they pay in. And the big lie is that they never tell you when they recoup. You could say, “Hey by the way, am I going to start getting royalties now for that last record I made?” And they’ll say, “No, we’re still paying off the expenses, you know. We took out an ad here, we took out an executive here, and we had a deal there, and we had a broiled salmon lunch there.” [laughs] And as a result, they can keep stringing you along and you never see a royalty.

Then also, think about the fact that let’s say [you] move on to your next record label. Everything that you have done on Blue Note is still on Blue Note. Maybe your sales weren’t really great on Blue Note, but suddenly you’re a hit on this other label. Well, because you’re a hit on that other label, out of the vaults come all of these rejected cuts and b-rolls that you did on the first label that at the time they said wasn’t up to snuff and wouldn’t sell. Now, since you’re so popular and the world is going crazy over your music, they look in their vaults and they start finding things that they can now release that you weren’t happy with initially. And they do things like try to ride the wave of your new success by repackaging some of your old CDs. Suddenly there’s a “best of” CD on your old label that you’re no longer with. Why can that happen? It’s because they own your music and they can do anything they want with it because they paid for the recording, they paid for the pressing, the mastering, artwork, all that stuff.

With [the crowdfunding model], I take the monies that we get – and I usually have to add my own money to it as well – and pay for the recording and the pressing and the cover art and all that stuff. But I own it. The thing about ArtistShare is instead of the old model where they keep ninety percent and give you ten percent or less in royalties, they take fifteen percent of all money coming in, and the artist gets eighty-five percent.

That’s a little better in your favor, eh?

I’ve never been with a record label where I get eighty-five percent of the monies taken in. That’s from day one when somebody says they’re going to be a participant. If a participant comes in at the basic level, then I get eighty-five percent of that. To me, it’s better all around.

I’ve never been with a record label where I get eighty-five percent of the monies taken in. That’s from day one when somebody says they’re going to be a participant. If a participant comes in at the basic level, then I get eighty-five percent of that. To me, it’s better all around.

So what advice do you have for indie musicians who are working grassroots?

I would say focus on the music and build your audience one participant at a time. Think of it as building your house and you’re going to build your house one brick at a time. When you build your house, you don’t get impatient. You can see that this brick is going there. It’s like, “I’ve got a house to build, but hey – I’m doing it!” To me, that’s what it’s all about. Just be patient and keep working. If you stop laying bricks, then the house isn’t going to get built.

But I think the focus needs to be about the music. The buzz that’s going to be created about you is always going to be about your music. It’s not going to be about who you know, who you date, who you marry, or how big your house is. No, it’s always going to be about the music. If you focus on the music then the other stuff falls into place.

In the press release for The Gathering, you mentioned your music is so steeped in the blues, and while some players get tired of the blues, you don’t. How do you keep things fresh?

I keep things fresh by thinking about the sounds of each person. First of all, mood kind of directs the compositions I write. So maybe I’ll think, “Ok, I need an exciting song.” Then I think, “I need an exciting song for Jeff and for Terrell [Stafford].” Then I start thinking about Terrell and Jeff’s sounds, and I think, “Where do I want to go with this,” because I’m hearing how they sound when they’re really exciting to me, and I’m hearing what Gerald is doing on the piano when he’s really exciting to me. When I have those elements in place, it takes me down whatever road. That’s what keeps it really fresh for me. I just think about the musicians and what they do and how they impress me, then I go from there.

So you look outside yourself.

Definitely. I know that I’m not capable of doing something like that. It’s coming from another source. You know, the universe, the spirit in the air, whatever it is. I’m just the conduit.

Do you feel very spiritual about music?

Yes, but not in a religious way.

Something I’ve realized recently is that I’ll be really enjoying a song and often find out later that you arranged it. How did you get into arranging?

I think I got bit by the arranging bug when I was in Count Basie’s band. I discovered [it] after a couple of months. One day, they said, “And now ladies and gentleman, the Count Basie Orchestra!”, and the curtain went up. I looked down and realized I had left my music backstage. That’s when I realized that I had memorized the book. That gave me the freedom to not need the book, though I’d have it there if he called a new song or something. But then I could really listen to what the band was doing and all those cool sounds.

I knew how to transpose for the instruments and I asked Count Basie if he would mind if I wrote a piece. He said to go ahead and I did. I brought it in and the band rehearsed it and it bombed. It was so bad. It just sucked. The guys were like, “Ok John! Alright man!”, but I knew it sucked. We had like a two week break and I went home and I took this record that the Basie band had made that I loved. It had a song on it we played every night called “Splanky,” and it has this amazing shout chorus. I just transcribed it. I couldn’t hear every note, but I transcribed as much as I could. I analyzed it, and I used a lot of what I learned from that to write my own song, which is called “Blues for Stephanie.” I went in and the band played it, then Count Basie said, “Let’s do that one more time.” It was very cool.

It would always be two steps forward and one step back, because as soon as I thought I knew what I was doing I would write something and it would really sound terrible. I’d try to edit it and stuff, and the guys in the band would say, “What are you doing?” I’d say, “Well I’ve gotta change this and change that,” and they would say, “Why?” I’d say, “Well, it didn’t sound right,” and they would always say, “Just write another one! Don’t try to edit the one you did. If there’s stuff you didn’t like – don’t do that!” They really encouraged me to write right, and that’s how I learned.

That’s a heck of a band to be able to practice your writing chops with!

You have no idea. I could call the saxophone section to my hotel room to read 16 bars of something I wrote just to see what it sounded like. The brass would rehearse 24 bars of something I’d written just before the concert. [They were] always accommodating. They never said no. It was very cool.

You seem like a really busy guy, because Paul McCartney’s Live Kisses DVD just came out, which you’re playing bass on. Can you tell us a little bit about what it’s like to work with Paul?

He’s one of the most normal yet sensitive, fun-loving, easy people I’ve ever worked with. He can laugh with you. He is totally honest about himself. So, he would say things like, “I don’t know what this chord is, but this is what I’m hearing. I don’t know what you call this, but this is what I’d like for us to do.”

For instance, one of the songs that we did was “The Glory of Love.” We did it and rehearsed it in the studio and everyone contributed ideas. Then we recorded it and when we were done, it was kind of like, “Ok, let’s move on.” But Diana Krall said, “Can we do that one more time? And this time, Paul, I just want to have it be a duet between you and John in the beginning.” So that’s the way we did it. He’s open that way, and that’s the kind of freedom that he encourages. That’s the kind of creativity that he’s about. So I highly respect that guy.

He also would make you feel comfortable. He never made you feel like he was a prima donna or that he was the great Sir Paul McCartney. Never. Not one time. Being in the studio, every day I’d see him. He’d see me and he’d walk over and give me a big hug. He initiated it – it wasn’t like I was.. [laughs] I thought, “Man, how lucky am I to wake up in the morning and have Paul McCartney give me a hug.”

I have to say it was an amazing experience, and he’s one of the loveliest people on the planet.

You’re a renowned educator, and you’ve been putting up new videos of bass tips. What are you hoping to get out of that?

I remember working on a video with Ray Brown, and his whole thing was he didn’t want the video to take the place of a private teacher. He wanted it to be something that a player could go to and reference at anytime they wanted to when they weren’t there in the studio with their private bass teacher. Here’s something hopefully that they could supplement what the rest of their life was about.

I’m kind of picking up on that theme. I know that there are a lot of people who are scratching their heads about how to do things. And maybe their school director doesn’t have the answers that they’re looking for, so I kind of was thinking from that perspective of “Ok, what are the common denominators that we all realize and that we all do?” You know: left hand, right hand, posture, etcetera. There are so many different ways of playing the bass and to me they’re all good unless they do damage to you physically. That’s the only criteria for me. If it’s hurting you physically then no, but other than that you can have the bass higher, you can have the bass lower, you can have the bass tilted, you can have the bass straight up, you can have the bass with an angled endpin, you can have a straight endpin. There are so many ways to play the instrument and they all work for the individual. So I try to find the common denominators and focus on those and also talk about the things that work for me. I use the angled endpin after 30 years of playing with a straight endpin. I know the benefits of both.

So it’s like that. I want my bass tips to naturally go wherever I see the need for some commentary and some visual instruction. Through the years with all the teaching I’ve done, I kind of have a list of things that I often say, and I’m allowing those things to guide how I make my bass tips installments. Stuff that you already know, like why should the elbow be more up? Well, because when you’re touching the strings on the fingerboard and your elbow is down, look at the shape of your hand and the shape of your wrist. That shape shows you that you’re going to have a blood flow problem, and when you have a blood flow problem and you have to use your muscles with that impeded blood flow, now you’re looking at possible severe problems. All those things are things we’ve learned as we’ve learned more and more about the bass and playing the bass. So, those are the kind of things that are on my list that I always talk to people about, and I’m just trying to kind of go down [that list].

For the good of the bass world, right?

[laughs] Yeah, I guess. I feel like it’s not about making a DVD to sell. I think for the most part those days are gone. As soon as you make a DVD, it’s going to be on YouTube. Why charge somebody for it, because eventually eventually everyone is going to have it free anyway.

Speaking of teaching, obviously you studied with Ray Brown. What kind of a teacher was he?

Demanding, but not unreasonable. Everything he said made sense. He’d say, “You have to learn all of your triads – major triads, minor triads. All of your chord types – major 6th, minor 6th, dominant 7ths, minor 7ths, major sevenths, minor with a major 7th, augmented 7ths, diminished 7ths. You have to learn all of your scales. You have to learn how to play the whole bass – from the scroll to the bridge.” He’d say, “You know, music is going to kick your butt enough. You don’t want to have the bass kick your butt, too.” He was relentless about that. He’d say, “You’re playing tunes. You’ve got to learn tunes. Learn them in all keys.” It was like that. He was tough, but not unreasonable.

Do you think that mirrored his personality?

Yes. I wouldn’t say tough when I talk about his personality. I would say strong. He was strong about what he felt and strong in his business practice. Strong in his conviction about the bass. But, he was such a community guy. He was such a village guy. He was totally about fun. He hated being in L.A. because he thought about the fun that he could be having touring. If he was home two or three weeks in a row, he’d say, “Get me out of here!” [laughs] He just loved playing. He was a remarkable guy.

So what’s next for you?

Next for me is a mixture of writing and playing projects. So I’ve got some commissions I’m doing for various ensembles. I’ve got that writing stuff to do. I’m going to bring out a new series on CD that initially will start out as a duo series. I’m calling it “The Parlor Series,” as if I would invite you into my home and into my parlor and say, “Hey, put your feet up. Here’s a drink, and so-and-so and I are going to play some music for you.” The first one is going to be out… I’m shooting for the spring. It’s going to feature my son and myself. I’ve already recorded two others – one with Hank Jones and one with Mulgrew Miller. So those are going to come out eventually, too. It’s just my own little bucket list dream. Stuff that I want to do, like make some duo recordings with people that I want to play with. Right now it’s piano but I expect to expand it. It could be guitar, it could be two basses, whatever.