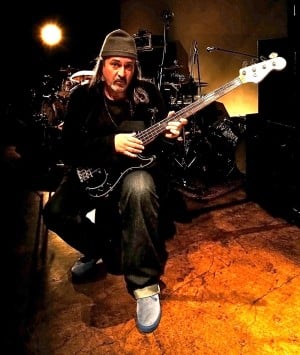

The Process: An Interview with Bill Laswell

Being on the cutting edge of music in itself is no easy task, but Bill Laswell has been doing it for over three decades. A man of many hats, Laswell has been pushing the boundaries of music as a bassist, a producer, an engineer, and a record label owner. While he’s worked in nearly every style, his true passion is discovering new ones.

Laswell’s prolific career has included over 3,000 recording projects by artists ranging from Motorhead to Matisyahu to Pharaoh Sanders to Whitney Houston to Mick Jagger. He’s credited with co-writing the seminal Herbie Hancock song “Rockit,” which subsequently pushed turntable scratching into the mainstream.

But it’s not popular success that keeps Laswell’s fire lit. His primary focus is experimenting and finding what he calls the “new things.” He often collaborates with musicians from abroad to mesh radically different textures and tones together while letting his intuition guide him. Laswell is not one to focus on the past and as such carries strong opinions on what he sees as important to furthering music in general.

His latest release is The Process, an album featuring the core trio of himself, pianist Jon Batiste, and Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith. What was first hatched as an idea for a full length film became the basis for a project that Laswell tinkered with and morphed into its own.

We caught up with the bassist to get the details on the album as well as his ideas on music in general, his gear, the making of “Rockit,” and much more.

How did The Process get started?

I met a guy who was beginning the early stages of becoming a filmmaker [named] Jay Bulger. We did some interviews together based around Lee Perry and then Ginger Baker. He had the idea of doing a film on Ginger Baker, which he did, and I did a little interview in that. [ed. note: The film is Beware of Mr. Baker] Chad Smith, the drummer, was also involved in that film. So Jay became acquainted with Chad and myself and he somehow met this pianist from New Orleans named Jon Batiste. He had the idea to make a film where three people go into a room with no fixed plan or any written music and just play and make a record, then they would film that. I think everybody thought that was this radical, revolutionary idea. Unfortunately, I’ve been doing that for like 25 years. [laughs] So, you know it wasn’t anything new to me.

The film didn’t really get made, but there was potential in some of the music so I thought maybe with some production and a little bit of listening, editing, overdubbing, and bringing in other artists that a record could materialize. That was my approach, and the result is that record.

Obviously, as you pointed out, you’ve been doing this so long that the concept isn’t new, but how did everyone else in the project take it? What was the actual process like?

Initially it was improvising. Chad is a rock drummer who has a great rhythmic sense and he’s interested in expanding. I think the way he said it was that it was out of the comfort zone, which is true. He tried a lot of different things… We were cross-referencing some African things and some established things that we all had in common. There were references involved so you’re interpreting these references. It’s pretty much improv, [but] I don’t believe improv exists if you do it all the time. You have a built-in repertoire and in some cases you have a secret language with certain artists that you work with. But from the point of the piano player, I don’t think he’s had a great deal of experience of just playing without a form. He comes from a very educated background that deals with form and structure and tradition. I think Chad comes from a background of dealing with patterns. I come from nowhere, really. A lot of it – probably about 80% of it – is improv, even production things are improv sometimes.

Could you explain what you mean when you say you don’t believe in improv? Do you think that it’s just tapping into a language you’ve already built?

On a higher level, yeah, if you are constantly involved with spontaneous interactions with musicians and in some cases consistent relationships with certain musicians who have established a voice or name or whatever. I think when I play with musicians in North Africa or some of the great Indian musicians or John Zorn or different drummers, a lot of it is playing a kind of repertoire, a built in language that exists. It’s a secret, kind of hidden music that can’t be explained. It can’t be described; it can’t be deciphered or analyzed. It just has to do with life experience that comes out of the instrument.

The instrument is just a tool. They teach you how to use the tool in every kind of aspect of the workplace. You build things, you take things down. It’s construction but in music you’re building constantly on this invisible kind of repertoire that you inherently have as you learn and again, it comes from experience. When I improvise, to me, I’m not improvising. I’m playing a set of some kind. There is a plan that can’t be seen, but it’s a plan. It can’t be told, but it’s a plan somewhere.

How do you think people tap into that? It’s just inherent in everyone and is just built through time?

Yeah. I think it’s propriety. It’s where you put your time. It’s how you invest. I believe thinking already is kind of negative, in a way. You have to feel things.

It’s all about what your propriety is. If you believe that training is important and education is important and establishing the understanding of the music systems the way they do in schools – if you value that and believe that’s important then that is your propriety.

Another way is to imagine that education is the number one enemy of intuition, and intuition is the key to new things. I mean, what would have happened if Jimi Hendrix went to Berklee? You would have never heard of him.

I assume that puts out your stance on higher education for music.

Yeah, I don’t believe in that at all. I believe those are just systems that are used and the only real system that comes out of that is that you’re emulating someone else’s work or idea. Everything starts with an idea. People that copy other people are copying an idea. A great deal of what happens with what happens – especially with music today – is copying other musicians. They may not admit to that and they may not even be aware of it, but it’s all cross-referencing what has happened that came before. If you look at pop music, it’s a continual regeneration or regurgitation of other successful formats. It’s repetitive. There’s nothing wrong with repetition, but for me repetition is African music and Indian music and not convoluted pop sensibility which is all based on, in some sense, classical music.

How do you make that connection?

Melodically and harmonically. Then you strip it down to its fundamental and its kind of cut and paste. Today everything is collage music, whether we want to admit that or not. Most popular music is a collage system. You take a verse from this one and a chorus from this one and a bridge from here… And your melodic content might refer to as far back as the Beatles, and that probably refers back to some contemporary classical piece that had melodic content.

Do you think that learning bass player repertoire is important?

No, I don’t think that’s important. I think for bass playing you first have to listen to the pulse. You have to first understand the repetition of pulse and rhythm, and I think you can hear that a lot in [world music]. What I was influenced by was the low end of West African drumming, then I started to hear Indian music and the low end of the tablas, and Afro-Cuban music with the conga rhythms.

No, I don’t think that’s important. I think for bass playing you first have to listen to the pulse. You have to first understand the repetition of pulse and rhythm, and I think you can hear that a lot in [world music]. What I was influenced by was the low end of West African drumming, then I started to hear Indian music and the low end of the tablas, and Afro-Cuban music with the conga rhythms.

As far as emulating American and European bass players, I thought it was interesting to hear them. Growing up, you’re naive. You don’t know any better and you listen to what’s popular. My influence around fifteen years old would probably be Chuck Rainey, Duck Dunn, or Jerry Jemmott and those guys. I was not into Motown because to me Motown were jazz musicians who couldn’t make it in jazz so they got a job. It was a little too busy for me. [James] Jamerson was too busy for me. There’s a couple of classic moments of what he did, but it’s not someone that I wanted to emulate or sound like. Over Motown I preferred Stax and Muscle Shoals and blues and country music.

Did your musical tastes blossom before or after moving to New York?

I think it’s kind of organic. It blossoms gradually, I think. I started playing very early because there was nothing else to do. It was either that or you’d be in some kind of trouble. I picked the bass because everyone else played guitars and drums, so there was a necessity for bass players. I started [bass] by taking a guitar and removing two strings. That’s how I started – I just did out of necessity. Then I realized that I liked it and it kind of kept going so I started listening more to things.

Before moving to New York I made some discoveries. A lot of it had to do with the beginnings of free jazz and improv, and especially African music. So I had that kind of interest before arriving in New York. Then arriving in New York I got lucky. I made the right turn on the right corner and ran into the right person. Everything happened very quickly.

Your career kind of exploded there. Of course, a lot of people came to know about you through Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit.” Can you tell us about that session?

Well, it wasn’t really a session. There was a guy called Tony Meilandt. He worked for David Rubinson, who was a big manager. Tony was much younger. He was younger than me. Around 1983, he came to New York and he was looking for things that would enhance Herbie’s situation. Herbie is one of those guys that every ten years he has a hit song and he was kind of overdue at that time.

So Tony came around and he went around the loft scenes, he went around the punk clubs, and everything and came across me. He was fascinated that at the time I was working with Brian Eno. When he made that connection that I was playing with Eno [he also found that] I was also playing in punk clubs, I was also playing free jazz with people like Phillip Wilson and those guys. He took a risk and said, “Could you make some tracks for Herbie?” I didn’t take it too serious. I thought it was probably going to be some experimental beat thing. Hip hop had just started in a sense and I had made friends with a lot of the people through Celluloid [Records] and Bernard Zekri, who was a French-Algerian journalist. We would go to Bronx River Armory and see all the emerging DJ’s.

So when it came to Herbie’s thing, I thought we’d use a turntable and some electro kind of beat. Something different. I think it happened in a couple of hours, really. The track was put together. I went to the West Coast to California and we put up two tracks. One was called “Earth Beat.” I was giving D.ST, the DJ, a lot of weird vinyl to play; things from gamelan music to Stockhausen and all this weird stuff he wasn’t used to, but he was using it. So the track was completely finished except for the keyboard. When we arrived, we went to Herbie and recorded at El Dorado, across from Capitol Records. We recorded Herbie probably in a few hours and mixed the track in less than an hour. We had no idea what it was. It was like, “Ok, that was cool. Now it’s over. Let’s get back to New York and make something that could get some success, but this is just experimental.”

On the way to the airport, it was me, D.ST, a guy named Grandmaster Caz. I have no idea why he was with us, but we had some time so we were passing all these stores that sell speakers. We were starting to make a little money, so we said let’s stop and check out some speakers and stuff just to kill time. We went into one of these places and said, “We want to hear these loudspeakers. Could you play this and this and this.” So the guy would play something like Kansas, and we said, “No, we don’t listen to that stuff.” I had a cassette of the mix for “Rockit” so he put it on and played it. About half-way through, there was this chill that everyone got. We turned around and there were like twenty-some kids standing there just looking like, “What the [expletive] is that?” I looked at D.ST and said, “This is gonna work.”

Because back then, the audience decided in a way. I mean, that was on the radio every two seconds. That’s pretty much how that happened. It wasn’t a master plan or a concept. It fell together so quickly. And it’s nothing – it’s just a riff. I think what translated was this new sound of the turntable. We kind of introduced scratching to the mainstream. It happened a little bit before, but not on that level of exposure.

Do you think there’s a natural tendency for bass players to be good producers?

I’m not sure. I never really wanted to use the word producer. I never wanted to be what they call a producer. I started getting that credit when I realized I couldn’t hear myself. Then later on it became interesting because you could do a lot of experimental things if you had budget, and to get budget you had to sell some records. It was kind of just a natural growing process.

As far as bass players doing that, I think that if they’re great and have a sense of feel and sound, then yeah they could be good for rhythm music for sure.

So you see yourself overall as a creator rather than a producer?

No. I don’t think it’s healthy to pin yourself down to any title. You could call it a producer, you could call it a collaborator, a futurist, an experimentalist… You could call it somebody who’s trying to push the avant garde and trying to push everything. I don’t think there’s an actual title that’s necessary. There are too many names to boil it down to any one in particular.

Could you give us a rundown of what bass gear you’re using right now?

It’s pretty much the same as I’ve been using for a while. I’ve got a Fender Precision bass but it’s all been insanely customized. I used to have a lot of instruments and I had them in a big loft. I just had piles of them. At the time I was playing a Wal Bass a lot but it didn’t travel well because depending on the climate, the neck was always crazy. One day I pulled out this black Precision bass that had a jazz pickup in it and a P-bass pickup in it. The neck was fretless but it had lines on it. The neck was a lot thinner than a Precision neck, but it wasn’t quite a Jazz neck. I really didn’t have much background on the instrument. I believe a guy named Ken Parker, who made the Parker Fly guitars, was the one that worked on it but I’m not a hundred percent positive. Anyway, I pulled that out and I really liked the tone so I just kept using it. It travels well and the intonation for the most part stays in.

For amplifiers, it depends on the room. I usually use Ampeg SVT. If it’s a big space I use heads and four cabinets. If it’s a small space, I usually use two heads anyways and two cabinets. I have the big SVT-215E Folded Horn bass cabinet and the big SVT-810E with 10-inch speakers in it.

For amplifiers, it depends on the room. I usually use Ampeg SVT. If it’s a big space I use heads and four cabinets. If it’s a small space, I usually use two heads anyways and two cabinets. I have the big SVT-215E Folded Horn bass cabinet and the big SVT-810E with 10-inch speakers in it.

The pedals change all the time. There’s a few standard ones that stay, but I just keep trying different pedals.

Is there one you’re really excited about lately?

I use a lot of low end, so there’s an old DOD envelope pedal [the Dod Performer Wah Filter 545 (Beige)], but I don’t use it as an envelope. I use it for the bottom. If you set it the right way, you get massive low end. They all sound different – every one I’ve tried. I found one that really works. I’ve also been using Pigtronix stuff a little bit and a [Digitech] Whammy pedal. There’s a Bass synthesizer pedal made by DOD, too.

You’ve put out so much work it seems you’re constantly working. Do you ever get writer’s block? How do you deal with it?

I think you hit it all the time, but it can’t last too long – that’s the key. You hit it all the time, but not so much [from] playing. Sometimes you get tired. If you’ve done a lot of things, you’re under a little bit of pressure to continuously reinvent yourself, which can be a challenge. You have to accept that [blocks] exist and realize you’re in the middle of it, but you have to get out of it.

Do you have a certain way of getting through a block?

I think it’s intuition. I don’t have much dependence on the known factor. I deal with more of the unknown. For me, something has to be magical and to be magical it has to be detached from all this rhetoric. I can be fairly lost a lot of times and I think that’s where the real value is: in the unknown.

Will we see another solo bass album like Means of Deliverance again anytime soon?

Yeah, I’d like to do a kind of similar one and use the fretless a little more and maybe use a string quartet. I have a guy who is a great arranger named Karl Berger, he’s a German musician, and we talked about doing string arrangements overtop of these minimal bass ideas. I hope in the near future I can continue that idea.

You’ve always got projects in the works, but what’s next for you?

I’m trying to do a lot of live stuff, if possible. One project is Master Musicians of Jajouka with musicians from Morocco in North Africa. We made a great band around that. Mokhtar Gania is another group that plays Gnawa music with the gimbria sinter, which is very similar to a bass instrument. There’s a trio with John Zorn and Dave Lombardo, who was the drummer for Slayer, [and] that’s been very effective.

As far as recording, there’s my label and we continue to build a digital label with a lot of experimental stuff but open to everything. A lot of work in Japan, a lot with DJ Krush, who is great. It’s a kind of continuation of the same but every once in a while somebody drops out and somebody new checks in. It keeps it alive.

Bill Laswell’s Gear:

| Bass: | Modified ’70s Fender Precision Bass |

| Amplification: | 2 x Ampeg SVT Classic Amplifiers, Ampeg SVT-810E 8 x 10″ Cabinet, Ampeg SVT-215E Folded Horn bass cabinet with 2 x 15″ |

| Pedals: | Ernie Ball Volume jr (passive pedal), Digitech Ex7-multi fx epression pedal (orchestra synth sound effect only), Crybaby Bass Wah, Moogerfooger Ring Modulator, Moogerfooger Murf, Digitech Whammy II, Electro Harmonix Bass Big Muff, Pigtronix Envelope Phaser, Digitech Bass Synth Wah, Dod Performer Wah Filter 545 (Beige), Boss DD3 Digital Delay, Boss DD7 Digital Delay/Looper |

| Accessories: | Ebow, Metal Slide, Alligator Clips |

Thanks to James Dellatacoma for the gear list.

Thank you for sharing this!

We go way back to Albion, Cee Wa Tu,

& Sonor Eclipse.

One word- Ahead of his times!!!!

Good interview , and a great outlook on the art of creating music,shared by Bill Laswell.

very nice