Diluvium: An Interview with Linus Klausenitzer

For some of us bassists, adding a fifth string is a stumbling block. That’s why it’s jaw-dropping to see and hear someone like Linus Klausenitzer, who tackles the insane music in Obscura with a six-string fretless. The German technical death metal band is not the kind of group that rests on their musical laurels, and the bassist wouldn’t have it any other way.

Always evolving, Klausenitzer and Obscura are gearing up to release Diluvium on July 13th. The record, which will be his second album with the group, is the final effort in a four-album conceptual series. Klausenitzer contributes to Diluvium‘s compositions in addition to delivering some of the best metal bass playing of the decade. Alternating between delicate and devastating, he utilizes the vocal register of his bass to bring out lead melodies throughout the tracks as well as a killer solo on the opening track. The bass is not lost in the mix and brings Klausenitzer’s personality to the songs, which is something he wants more bass players to do.

In addition to his work with Obscura, Klausenitzer also plays with Alkaloid, who just released their sophomore album Liquid Anatomy. He regularly gives bass clinics around Europe, so be sure to check his Facebook page for more details.

We caught up with Klausenitzer to talk about his love of Steve Harris, his writing style, working as a session bassist, and how bass players need to bring their own character back to the instrument. Read to the bottom to hear the latest Obscura track.

You have a lot of little solo breaks throughout Diluvium. Do you consider those solos or just lead melodies?

I never consider them as a solo, [it’s more like] I have a lot of melody parts. The best moments when I can express my phrasing and my voice are the mellow parts where you have clean guitars and all the dynamics of the songs come down. On the new album, there’s one song where I have an actual bass solo with distorted guitar, but I rarely do that.

I know you wrote a few of the songs. What was the writing process like for this album?

I wrote about a third of the album. It was pretty equal from everybody, which is pretty new because on the last album, Akróasis, our drummer Sebastian didn’t write any songs. On this one, everyone contributed, including our new guitarist Rafael. Rafael and Sebastian both have a music college related history like I did while Steffen is more of an autodidact. He has a totally different way of writing. He sits down with a guitar and plays riffs to find good ideas. I suck at guitar, so when I write an Obscura song I do it on Guitar Pro to write ideas down and then I ask the guitarists if they can play it. I program a little bit of drumming, but only very basic.

I wrote about a third of the album. It was pretty equal from everybody, which is pretty new because on the last album, Akróasis, our drummer Sebastian didn’t write any songs. On this one, everyone contributed, including our new guitarist Rafael. Rafael and Sebastian both have a music college related history like I did while Steffen is more of an autodidact. He has a totally different way of writing. He sits down with a guitar and plays riffs to find good ideas. I suck at guitar, so when I write an Obscura song I do it on Guitar Pro to write ideas down and then I ask the guitarists if they can play it. I program a little bit of drumming, but only very basic.

We had a lot of Skype sessions. Normally one guy comes up with a very raw idea [for a song] like the main riff, the verse, and a chorus. Then you build the rest with the guys and you work on it. That’s how it happened with almost every song, I think. If I came up with the main idea, it mainly started with one idea that I had as a basis. That could be rhythmical or whatever, but what I really like is sitting down and writing eight bars of chord changes that I have never heard in metal. That’s how we write songs – by pushing into new territory. Obscura is very challenging and very complex, so that’s our tool of writing differently from other bands. It’s our way to make ourselves different.

So I try to write changes that weren’t there before, usually based on a lot of jazz theory. I try not to make it sound jazzy but [instead] sound dark, and I have a method to do that. Then I have the chord changes and I start to write guitar pitches on it or I start to make a bass line. Not walking bass, but lines that go through the chord notes. You can then take notes out of the chord then you write a riff with it. You have a lot of possibilities when you have that one main idea. Then you can get creative, but the main idea has to be good.

It’s interesting to hear that you write from a theoretical position because I don’t think a lot of people do in metal. How much of that comes from your upbringing since your parents were musicians? Were they classical musicians?

Actually, they were. My father still is. He’s now 73 so he’s kind of retired but for a 73-year-old person, he’s very active. He still plays concerts in Japan and he was in India last year. He’s a conductor and a violinist and for a very long time, he had his own orchestra. He also has a short guest appearance on this album, actually. There is one part that has strings and he plays violin on it. It’s the first time we are on a record together. It was very exciting. We played a concert together already with metal bands and his orchestra, which was exciting for me. Our guitarist, which also plays in my other band Alkaloid, he’s a classical composer. That’s his main job. He wrote a piece for orchestra and metal, so we played two concerts like that. It was very exciting.

My mother is multi-talented. She has a cafe and used to play in an orchestra on the trombone. She also played in a German folk music band playing trombone and accordion. The group was called the Bavarian Seven, and it was seven women that played in Dirndls. Like the German stereotype you have in your head, it was exactly like that.

You also play trumpet and piano, right?

That’s correct, but I wasn’t very good. For me, the bass is the one instrument. It wasn’t like, “Well, I played trumpet and piano but ended up with the bass.” I always liked to listen to music, and when I was young I listened to a lot of jazz. When I was 13 or 14, I got into Iron Maiden and said, “That’s it! I want to play bass.” I never wanted to play guitar. I’m not one of those people that switched from guitar to bass. Bass was always there.

I think Steve Harris is responsible for half of all metal bass players.

He’s still a god for me. But anyway it’s the typical tech/death [metal] bass player story: I like Steve Harris and my parents are musicians.

How did you go from Iron Maiden to a six-string fretless?

When I started, the first four years or whatever before college, I played everything like Steve Harris. I didn’t pluck or pull the string, I just hit it with my finger and got that percussive sound from hitting the fingerboard that I love. When I went to music college, we had a jazz jam on the first night. I had no idea what to do. They put a Real Book in front of me so I said, “I want to try everything I can. That’s why I’m here.” I think I didn’t play too bad, actually. I could play all the chord changes because I had musical knowledge from harmony theory already, but I played like Steve Harris with that attack. It probably sounded horrible. I had a good bass teacher that showed me all sorts of styles and I played everything from Jaco to Dream Theater to Cuban music. I wanted to know everything.

The goal of the school was to make everyone multi-talented so you can cover everything a little bit. Now that I’m actually a working musician, I know that this was total bullshit because that was how it worked in the ’80s and it’s not how it works anymore. Musicians don’t work like that anymore. You need to have that one thing that separates you from the rest of the world. In the ’80s, you had to compete with people in your local area. If you lived in New York, you had to be better than the other musicians in New York. Now you have to compete against the whole world because you can book studio musicians everywhere. I also live as a session musician, but from my home. Since everybody has a home studio and is recording metal albums from home, it’s normal for you to book metal musicians from your favorite records. If somebody has the new Obscura record and says, “Hey I like that guy. I have a family, I’m still playing death metal since I’m 16. I’m writing songs but I don’t want book a studio or find people to play with. I’ll just write my songs and have him play on it then mix it myself.” That’s what happens very often, so that’s how I live as a studio musician. I’m [known as] the six-string fretless bass dude. I’m very fortunate. For example, I work with people from Lebanon and Pakistan and everywhere. It’s amazing. It’s super interesting the music they bring in and I learn from that.

To get back to your question, after music college I was hating the world. I realized if I didn’t want to teach guitar to children, I basically don’t know how to survive as a bass player. Then I had a few years of working in IT and I played in metal bands just for fun. That led to the connections with the band I had the orchestra concerts with, and from there some of the Obscura guys were in those concerts. Everything started to come together.

I played a few times on a fretless, but I didn’t even have a six-string fretless bass before I joined Obscura. I think it’s helpful if you play in a band for three years or longer and playing the same songs, then you can work on them and you can really understand the songs and the style. You can also work on yourself. I didn’t become much better from a technical point of view, but my musical character really grew in that time. If you want to have a musical character, you need to play a long time in one band. If you listen to all the session guys, they have a lot of skills but they don’t have their own character, really. Then you have those guys that play in one band for their whole life and they often don’t have any knowledge. If you put them in another band they would probably be lost. It’s just two different concepts of being a musician. I’m lucky to be a mix of it, I think.

How do you tackle playing six-string fretless on such intense music? What do you do to play in tune?

It’s hard to say. First of all, if you play very deep music and very heavy music, you don’t have to be exactly in tune. If I hit a note not quite perfectly that’s a sixteenth note at a tempo of 220, nobody will realize. The high notes have to be there, of course.

I think Ibanez just made a good bass, to be honest. With other basses, I have problems but not with these. I don’t know the exact reason why they are so easy to play for me. The bass that I’m playing right now is not available as a fretless; they made it fretless for me.

If you talk a little bit about cheating, vibrato always helps. Chorus helps a little bit to make it safer, as well. I also realized that strings can make a difference. Right now I want to switch my bass strings and I’m trying different companies and materials. I realized that some companies are easier to play in tune with and some are not. Maybe I’m just used to this one company, I don’t know.

The tone you get is incredible, and it cuts through just right. You can hear the bass, which is not always the case in metal. Do you have a philosophy about tone or do you just do what fits?

I’m a ’90s kid, so when I started to listen to metal the popular music was Korn, Limp Bizkit, Papa Roach, and so on. Now I can dig it but back then I didn’t enjoy it. Like I said, I started with Steve Harris and then I found Black Sabbath with Geezer Butler and Led Zeppelin. I realized, “Wow, all those bassists have an incredible musical character.” They’re all icons and had their own weird way of bass playing. For example, John Entwistle’s right-hand technique was very unique. Steve Harris’s was as well. Also, people like Billy Sheehan came up with something that wasn’t there before. Chris Squire was another great example. He had a very unique tone and a very defined color that he added to the music.

In the ’90s, bass players started to all have the same standard sound. That was horrible to me. It became worse and worse and worse. I’m happy we always work with the same producer because I’m scared that if we go to another producer I’ll have to tell him why the bass has to be louder than on another record. My theory is that after the ’80s were a little bit too busy for people to listen to, grunge came as the total opposite of it. Metal in the ’90s was very riff oriented. The riff was the center of every song, especially in thrash metal. Thrash metal is a good example because there’s a point where they didn’t give a fuck about the vocals anymore. If you listen to the first albums from Megadeth and Metallica, you realized they cared about good riffs and not about the singing. Everybody was focused on the riff, so the bass players had to follow the riff. People misunderstood and said, “Oh, the bass player just plays the same thing as the guitar player down an octave. He must be dumb.” People misunderstood that and the bass just became a frequency filler. Now you have bands that only program bass or they don’t even use bass anymore since they have 8-string guitars.

Right now is the perfect time to bring the character of the bass back into the music. Eight-string guitars have a very broad and fat sound, so for some bands the bass is obsolete. Our instrument is not even a hundred years old, so it would be very arrogant to say, “Ok, we need it forever.” But every time I see a band that’s playing without a bassist, I don’t feel the groove. It’s not punchy, it’s not brutal. It’s like something is missing. That’s why I think we still need bass very urgently. Now is the perfect time to come back with character especially since the guitars are giving us more space again. Guitars are getting lower and lower so you have a whole frequency range that is free. That’s what I’m doing with my fretless bass. That is where I go in and play my melodies and my parts. That’s why I think the fretless bass makes so much since and that’s why you can hear me so well. If there’s a guitar melody in the same frequency range, I don’t play a bass melody there. Also, of course, for a fretless bass you have that typical midrange sound around 280 hertz or something. Then you can hear yourself on the record. On the lower parts I have very deep bass on it. I mostly like the sound of the single coil bridge pickup because they have a very direct sound that also helps getting through. So those are the technical parts of how I try to get through.

A “Diluvium” is like a huge wave. Does the album have an apocalyptic theme?

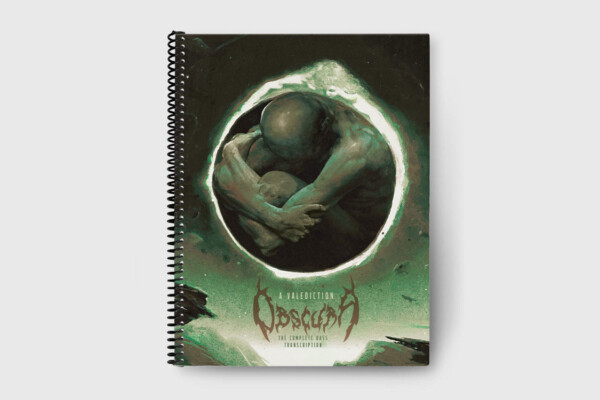

Exactly. We have five albums out with Obscura. The second album was the groundbreaker for us that had an impact in the metal scene and had a stable lineup. Back then, Obscura signed a four-album deal with Relapse Records. Then Steffen came with the idea of making a four-album concept. It’s about the life cycle and is based about a lot of astronomic topics about worlds and universes. The first album is about the creation, the second album Omnivium is about evolution, and the third album Akróasis is the philosophical one. It’s where people don’t just live and evolve, but they start to analyze themselves. Now the last one is Diluvium that has an apocalyptic theme where everything is going down. The album cover is very dark with black red to represent blood and fire.

We also tried to make the concept on the album start with a chaos and then the last song is kind of slight in the beginning then becomes very dissonant and powerful for a huge ending. Then to recreate symmetry, after every end you have to start with something again, and that’s actually when I play the bonus track which is a pure bass song. I only played it with an Ibanez Ashula seven-string hybrid bass. It has four fretted strings and three fretless strings. All the sounds come from the bass. I used a lot of reverb and made some percussion effects on the bass, too. The harmonies and melodies that I took from there are again from the same riff on the first song of the album. We love to play with symmetry. The concept is really everywhere.

I was going to ask you how it felt to play a bass solo for the end of the world, but it sounds like it’s the dawn of something new.

Exactly, the bass sprouts from nothing. Then you can start it over again with [the first album in the concept] Cosmogenesis if you want. It’s a lifecycle. It’s a returning thing.

The first song “Clandestine Stars” has a killer bass solo. Is there a metric modulation in there or is it just a feel change? How did you write it?

It’s just a feel change. I just put it on a loop and improvised a little on it, keeping the ideas that I liked. I used the ideas and connected them, so it wasn’t too hard. Other parts of that album are very complex in a rhythmical sense. Sebastian, our drummer, also plays in a band called Panzerballett and they work a lot with polyrhythms. He’s super smart about the topic. That makes his writing style very unique. He tries to bring in these really complicated rhythmical moments but he brings them in so they sound flawless. He came up with the idea for that time break. It works and makes sense. He’s a great rhythm partner and also I grow and learn from him.

That’s what I love so much about this band. Playing in a technical death metal band, it takes ten times longer to write a song, to learn a song, and to record a song. It’s very exhausting and it’s not the most commercial music of the world, but there’s a progression and you learn from the other musicians. It’s one of the few bands that the people understand the role of the bass and they want me to do crazy stuff. Most German bands and metal bands can be very conservative. They don’t want a lot of changes. In our scene, it’s different. They want a lot of changes and they want to be as crazy as possible. That’s a big privilege for us.

Although I play the six-string fretless bass, I also love to play four-string fretted basses. I have a Fender Jazz bass that was my first bass and oftentimes I like to pick it up to play old classics. I still do that, but the six-string fretless is what people book me for and where I have my own style, I guess.

Tell me about playing on the title track.

That song came mostly from Rafael and Sebastian then I added my bass lines. I don’t think I wrote one part of the song, although all of the bass lines from the album are all me – I wrote them all. The challenge for songs that already almost done like this one was is that I need to think of what the bass will do. I don’t want to be bothering with the bass but I want to keep it interesting.

For me, the most important thing in a song is the dynamic and working to support that dynamic. That’s what makes a story or a song interesting. If it’s flat, it’s not very interesting. The role of the bass player and every musician on the song is to support the parts of the song, so that’s what I tried to do. When there is a mellow part, I don’t want to play a fast bass solo on it because that’s for the listener to come down a little bit. If there’s a busy part, I like to add even more parts to make the listener say, “Whoa, what’s going on there?” That’s how I roll. You always have to create tension that has a release afterward, so I try to support those effects. That’s how I write my bass lines. I also try to redefine myself all the time. Sometimes I play the same thing all the time and get sick of it. Then I’ll sit down for an hour to figure something new.

It sounds to me like you’re not happy just playing the same stuff. You’re always trying to push yourself.

Absolutely. That’s always been my problem, even with writing songs. When I was younger I wouldn’t write songs because I’d be bored by my own ideas. I also don’t like improvisations so much because I think if I can compose it will be better. Of course, I understand the feeling of being in the moment, but I just prefer composed music and I’m not very good at improvising. If you compose something, you need to get out of your habits. You have your routines because you have limitations. Then you think, “What can I do to get out of that?” That’s where you have to have methods. That’s where I like to bring up music theory because I wouldn’t come up with complex chord changes without it. It’s why I like to have a very theoretical way of writing songs. That’s why people always think we care about virtuosity and theory too much, but it’s still emotional for me. When I write music like that I still have my ecstasy moments. If I don’t feel it and get into it then I don’t keep it.