Bass Transcription: Dave Hope’s Bass Line on “Carry on Wayward Son” by Kansas

This is a song that pretty much every rock music fan will know but probably can’t name the bass player. To be fair, I don’t think many people could name the members of Kansas nowadays, but this song lives on, played regularly on classic rock radio stations forty-three years after its release, and it reached a wider audience after its use in the fantasy drama Supernatural.

The Kansas sound is perhaps best described as a combination of complex British progressive rock (Yes, Genesis, Gentle Giant) with an American rock groove and instrumentation. The songs were often multi-sectioned and rhythmically sophisticated but retained a strong sense of melody and this, their best-known song, is no exception.

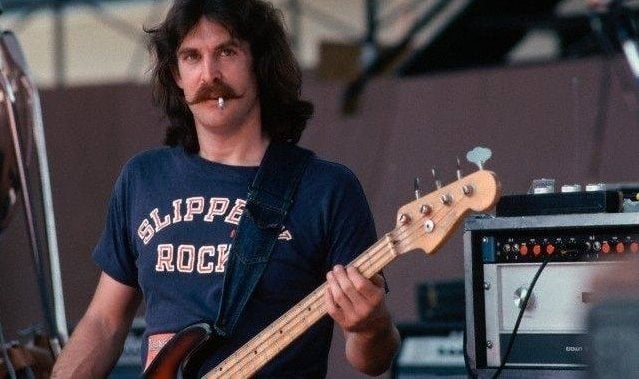

The bassist on this track was Dave Hope, who was born in Topeka, Kansas in 1949. When he was in the third grade, he started to play the trumpet, and later progressed to the tuba. At sixteen he started to play the bass, and joined his first band with some friends while he was attending military school. After this, Hope was in many local bands, and the music scene around Topeka was very fluid, with bands forming and breaking and changing their line-ups on a regular basis. Soon after this, the band was invited to play at the 1969 New Orleans Pop Festival, which also featured Santana, Janis Joplin, and The Grateful Dead. Joplin was complimentary about the band, and they hung out with her backstage. After the festival, the band returned to Topeka and continued to gig around the local circuit.

In 1970, White Clover merged with Saratoga, a rival Topeka band that featured guitarist Kerry Livgren. The new band named themselves “Kansas,” and they began to gig regularly, occasionally supporting major artists. In a strange turn of events, a year after their initial encounter with Morrison, the manager of The Doors invited Kansas to support them in New Orleans. After The Doors’ main set, they were called up onstage for a final blues jam, little knowing of the importance of the performance – as this was to be Jim Morrison’s last show before he died.

Frustratingly, even though they worked hard to generate a following, they had little record company interest. In 1971, Hope and drummer Phil Ehart decided to leave and re-form White Clover. Although Kansas carried on with other musicians, White Clover fizzled out when Ehart went to England to engage in his preferred ‘British’ style of rock. While Ehart was in England, Dave Hope joined a covers band called Plain Jane, but when the band downsized, he left the band. When Ehart returned, he reformed White Clover and asked Hope to return to his role as bassist. Kerry Livgren also agreed to join from the second Kansas line-up, causing the band to fold.

White Clover tried to gain record label interest, but with no success. However, in 1973, a demo tape was heard by TV producer Don Kirshner’s assistant, and after they checked out the band at a gig, they were finally signed. Kirshner was impressed by their song “Can I Tell You” and encouraged the band to start recording. At this point, the band decided to re-name themselves Kansas, and their self-titled first album was recorded at the Record Plant in New York. It was completed in three weeks, but would not be released for another year.

The band’s early albums didn’t sell particularly well, but they gained a solid following for their live shows, again opening for major bands like Queen (on their first US tour in 1974-5), Bad Company, and Jefferson Airplane. Kirshner also gave the band some nationwide publicity by featuring them on his syndicated TV show, Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert. However, the label became frustrated at the lack of commercial success, and Kirshner pushed the band to write more radio-friendly material. Despite this pressure, the band continued to create long, technically intricate songs with complex arrangements, and this eventually paid off.

Their fourth album, Leftoverture (1976), contained the single “Carry on Wayward Son” which reached number 11 in the US pop charts, and also found success in the UK and Canada. The song sold over a million copies in the US – helping to push the album to number five on the Billboard charts – and would itself eventually sell more than four million copies. The single “Dust in the Wind,” from their next album Point of Know Return (1977), was also a million-seller and helped cement their success.

With commercial success came the opportunity for some of the band members to embrace the “rock star” lifestyle, and indulge in the excesses available to them. Hope began to drink heavily and “graduate to more expensive [drugs]”, allegedly spending $40,000 on cocaine in one year. However, during the recording of Monolith (1979), he began to follow a more spiritual path. Both Kansas guitarist Kerry Livgren and incoming vocalist/guitarist Jon Elefante became born-again Christians, and Hope was influenced to follow the faith by his bandmates. After recording the album Drastic Measures in 1983, he and Livgren left to form AD, going on to record three albums of Christian-influenced rock.

In 1990, Hope re-joined the original members of Kansas for a European tour, but he did not stay with the band. In 2000, he revisited his role with Kansas when he played on two tracks on the album Somewhere to Elsewhere. Hope’s faith brought him into deeper connections with the church, and he was ordained as an Anglican priest in 2006, but he retired from the role in 2013. He is currently head of Worship, Evangelism and Outreach at the Anglican Mission in Destin, Florida, and still plays bass with the praise band The IRS.

During his time in Kansas, Hope mainly used Fender basses; Precisions with rosewood and maple necks, and occasionally Mustangs. He has also played Musicman, Kramer. Steinberger, G&L and Ibanez basses. During his career, he has used Ampeg, Marshall and Crown amplification.

Carry on Wayward Son

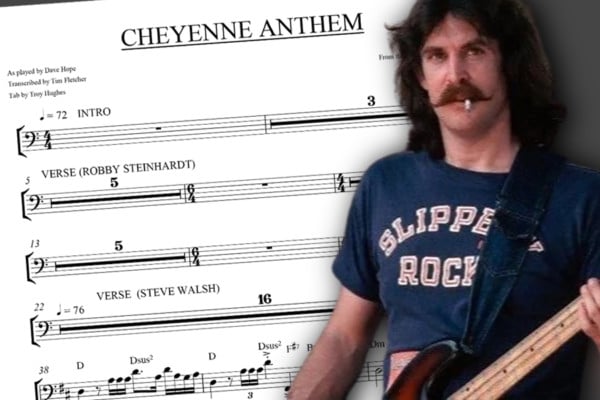

The song starts with an arresting 8-bar A Capella vocal section, followed by a powerful three-bar unison riff with some off-beat accents. After two cycles of the three-bar riff, a 12/8 section begins, using an open E and its octave, interspersed with a run based on Em pentatonic. This riff is repeated four times before the initial 4/4 riff is repeated twice, followed by the second riff twice before the bar of crotchet triplets (bar 33) that ends on a low F note.

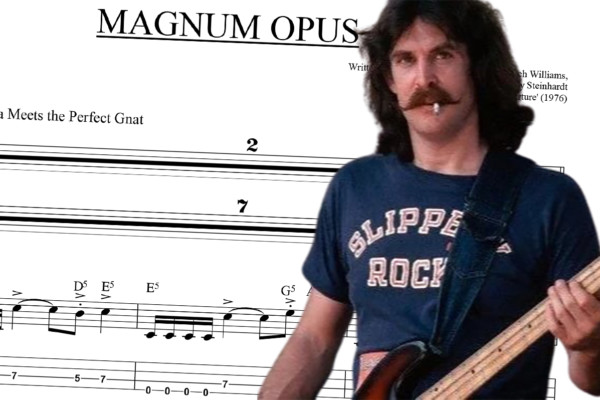

A bass free verse follows, and the bass does not return until the end of bar 43, where a quaver pickup leads into a simpler figure behind the pre-chorus and chorus. The intro riff returns at bar 59 for six bars before a more complete verse and then a chorus. This sequence stops at bar 87 where the bass line stops on beat one of a bar of 6/4. From bar 88, a new unison riff, again based around Am pentatonic begins, but with more semiquaver movement and off-beat syncopation than before. This leads to four bars of another riff, based around E Mixolydian, and again emphasizing the off beats. The two riff sections are then repeated, and then the original six bar riff returns at bar 112.

At 118, the pre-chorus returns, but this time beginning with a stop-start idea, and the chorus returns at 126, again ending on a 6/4 bar. This time, however, it leads into the 12/8 riff previously seen at bar 29. At 141, another new unison riff begins, this time based around the F# minor and E blues scales. A 6/8 bar at 148 begins a repeat of these two chunks, and finally, the crotchet triplet idea first seen at bar 33 leads to the final bar.

The many changes of key, time signature and scale add to the complexity of the song, but the various riffs are catchy and relatable to a mainstream rock audience. The vocal sections are more straightforward, and the vocals themselves lend a soaring and uplifting sense to the song. Hope’s playing is driving and accurate throughout, even on the more challenging sections, and he locks in extremely well with both Phil Ehart (drums) and the guitarists Rich Williams and Kerry Livgren. His tone is full and has an edge that helps to define the bass well in the mix.

Follow along with the transcription and this video:

What a great post, Tim thank you !!

Thanks! Glad you liked it.

I currently have Dave’s Marshall 4×15 bass cabinet that I bought from him in 1976 during the leftoverture tour. It’s an awesome cabinet. I haave played and toured with it for the last 40 years. It’s still amazing. May sell it one day. Getting too old to haul that thing around.

Hi Phillip. Keep checking out No Treble – more Kansas stuff is on the way…

jeezuz, 4x15s? That must be a beast!

Oh that was a lot of fun. Didn’t know that song at all. What a nice read. Many thanks.

Thanks Gareth – much appreciated!