Bass Transcription: Ronnie Baker’s Bass Line on “Bad Luck” by Harold Melvin and the Bluenotes

During the 1960s, many record labels developed their own signature production approach and musical style which helped to give the artists assigned to the label a readily identifiable sound. This was often encouraged by using a favored group of studio musicians. At Motown it was The Funk Brothers (with James Jamerson being the favored bassist); Stax used Booker T and the MGs (Duck Dunn) and at Philadelphia International Records, it was MFSB.

During the 1960s, many record labels developed their own signature production approach and musical style which helped to give the artists assigned to the label a readily identifiable sound. This was often encouraged by using a favored group of studio musicians. At Motown it was The Funk Brothers (with James Jamerson being the favored bassist); Stax used Booker T and the MGs (Duck Dunn) and at Philadelphia International Records, it was MFSB.

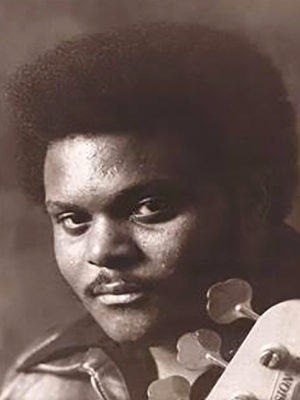

The core of MFSB was the rhythm section of bassist Ronnie Baker, Earl Young on drums and guitarist Norman Harris, and they played on hundreds of sessions for a range of pop, soul, R&B and disco artists including Wilson Pickett, Dusty Springfield, The O’Jays, The Stylistics, Billy Paul, B. B. King, Stevie Wonder, The Village People, and The Temptations. The trio also had a long-time connection with The Trammps, composing many of their songs (some were written by Baker alone), playing on their recording sessions and also producing their records, including their huge hit “Disco Inferno.”

Baker was born in 1947, and by the late 1950s, like his future collaborators Harris and Young, he was playing regularly on the club scene around Philadelphia. The trio was to begin their collaboration in 1963 when they were hired to play in The Sam Reed Orchestra at The Uptown Theatre in Philadelphia. This was a well-known venue on the Chitlin’ Circuit and hosted performances by many of the Blues, Jazz and R & B artists of the day. Reed had originally been engaged to oversee the visiting musicians appearing at the venue, but when Jackie Wilson was booked, he only brought a drummer. Reed hired a team of Philly musicians to back Wilson, and this included Baker and Harris. When Wilson’s drummer was late back from a break one night, Earl Young stepped in to cover him. Baker, Harris, and Young became the permanent rhythm section in the club’s house band, backing whoever appeared at the venue, including Motown acts such as Little Stevie Wonder. The orchestra worked very hard – they would play three to five shows a day, and as many as eight on Sundays – and Baker, Harris, and Young gained useful experience as a rhythm section.

Later in 1963, Harris and Baker were hired on the same recording session for The Tiffanys, and they worked alongside Bobby Eli, a guitarist friend of Baker. Later, Baker recommended Norman Harris (his girlfriend’s brother) for sessions he’d been hired for, and by 1965, the trio was completed when the sessions for Barbara Mason’s 1965 hit “Yes, I’m Ready” included Earl Young after the hired drummer didn’t show up one day. The song was a hit, and subsequently, the trio of musicians was often hired as a unit for sessions as producers would know that they would work together effectively.

As the trio began to work more regularly on sessions, they developed a close musical relationship, as Earl Young testifies; “…the three of us being together all the time, we knew exactly what the next person was going to do. I mean, that’s incredible. I knew what he was going to play, how he was going to sound”. Baker used to sit close to Young to be able to see his foot to help lock in with the bass drum, but the bass player had a tendency to play behind the beat a little. Bobby Eli reported that although Baker “always kept people laughing” on sessions, he was “studious and dedicated to his craft.”

Baker, Harris, and Young became well-regarded session musicians, and by the late 1960s, they were invited by producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff to play on sessions for artists on the Atlantic Records roster such as Dusty Springfield and Wilson Pickett. Gamble and Huff also hired them to record with The O’Jays and The Three Degrees who they had signed to their own label, Neptune.

When Neptune folded, Gamble and Huff formed Philadelphia International Records (PIR) and signed many of their former Neptune artists to the new label. After a visit to Motown Records, Gamble and Huff decided to use the same format of an in-house production team and access to a roster of high-quality studio musicians. As they had already been used on successful recordings by Gamble and Huff, Baker, Harris, and Young were hired to join PIR’s stable of around thirty musicians who quickly chose their own name MFSB (officially “Mother, Father, Sister, Brother” but allegedly meaning a more offensive term). Although most of the session work at this time was with the PIR roster, MFSB also had hits in their own right; The theme from Soul Train was a hit, renamed “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)” and MFSBwent on to record five LPs. Baker shared bass duties on these with future session legend Anthony Jackson.

Baker, Harris, and Young soon became the main rhythm section within PIR and were allowed a certain amount of creativity to create their own parts. Although the horn and string charts were arranged beforehand, often the rhythm section was simply given chord charts and a structure. This freedom helped to create great music, but also sowed the seeds of dissent in the musicians. Earl Young commented that; “Huff would come in and play us piano, but he could sit there and play that piano all night long, it wouldn’t be nothing until [Baker] came in with his thing…you know, these are things that you don’t write on charts…it’s a Gamble and Huff song but they didn’t tell us what to play on that, so the Sound of Philadelphia is based around all the musicians living and the ones dead”.

As the PIRs success grew, the musicians began to feel that they were often doing more work than they were being paid for – a flat session fee often included writing and arranging the material. In order to gain a better financial position, Baker, Harris, and Young started Golden Fleece Records – a record label and publishing company. One of the first acts they signed was The Trammps – the trio had produced and played on The Trammps first album for Buddah Records, and written much of the material. Young also sang bass in the group. However, Golden Fleece found distribution a problem and The Trammps eventually moved to Atlantic. Their later records were still produced by Baker, Harris, and Young, including their smash hit “Disco Inferno.”

The connection with PIR was gradually unraveling by the mid-1970s, and when the newly founded New York label Salsoul wanted to hire the best musicians to back their artists they approached the MFSB team to scout for potential players. Salsoul founder Ken Cayre was a huge fan of the “Philly Sound” and he discovered that many of the MSFB team were willing to make the transition to Salsoul due to the ongoing business disputes with PIR’s owners Gamble and Huff.

Cayre was very impressed by Baker’s bass playing; “Ronnie was a genius, I mean, he made up the O’Jays bass line for their hit “For the Love of Money” – that was Ronnie just fooling around in the studio and they made a song out of it”. Cayre also recalls Bakers other skills; “He also produced Eddie Holman’s “This Would be a Night to Remember.” he also wrote the song, played on it, arranged the strings and horns, and mixed it”.

As their skills became in demand at Salsoul, they formed Baker-Harris-Young Productions and created dance-oriented hits for Loleatta Holloway, Double Exposure (including the first commercially available 12” single “Ten Percent”), First Choice and Love Committee. The trio also created their own self-titled album for the label in 1979 and recorded and performed with The Salsoul Orchestra. This “orchestral disco” group were a big influence on Chicago House artists like Frankie Knuckles in the 1980s and a source of samples for Hip-Hop artists such as Eric B & Rakim, and 50 Cent. Salsoul ceased operations in 1984, but Baker continued to play sessions and gigs until just before his death in 1990.

During his career, Baker played a number of different basses including a Fender Mustang but is best known for using a Fender Precision Bass heavy-gauge flat-wound strings, and an Ampeg B15 amplifier. Baker was a big fan of the work of James Jamerson, another Precision user, and like him, Baker was reluctant to change his strings or even clean them. Bobby Eli recalls; “…his strings were probably ten years old and had grit, dirt on it, that was part of the sound. If you gave him clean strings, it just wouldn’t work. You had to have the dirt and the old funk and everything”.

Bad Luck

The bass line starts with a slide into a long melodic phrase based around an E Mixolydian scale which ends on a syncopated open E note. This is played twice before the main verse begins. The verse bass line begins with a simple root/fifth/octave idea, and then uses a contrasting busier, more chromatic line for the second half of the verse. This also uses some chromatic movement to add some flow to the line, reminiscent of James Jamerson’s work at Motown. These verse sections are repeated.

The chorus bass line is more straightforward but utilizes major sevenths and major sixths to sweeten the line to reflect the major seventh chords here. The chorus ends with a descending idea that spells out the E7 chord but in reverse.

Two more verses and choruses are then played, with occasional variation in pitch and rhythm, followed by another six repeated choruses. After this, the intro idea returns, followed by a long outro where Baker improvises around the initial verse riff, but at bar 155 he begins the intro run again, but this is not completed – this could be an error.

In the outro section, at bar 165, Baker changes the line to a simpler idea based on octaves of the open E note, and a more spaced, syncopated rhythmic idea. This is repeated to the end of the track.

Baker’s line in this track is quite repetitive, but occasional variation helps to keep it interesting, and the song grooves along very nicely due to his driving but flowing playing. The variation between the funkier verses and sweeter, more flowing choruses is effective. Baker’s playing here could be seen to be the bridge between the R & B playing of Jamerson at Motown and the overt disco playing of Bernard Edwards. The bass line is interesting, and complex in places, with melodic flourishes, but this is meant to be a song to be danced to, and Baker certainly makes his bass line fit that aim.

Download the transcription and follow along with the track:

I could be wrong but, The O’jays for the love of money, the Bassplayer and co-writer is Anthony Jackson, not Ronnie Baker, A.Jackson has writer credits

To back up my previous statement:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/For_the_Love_of_Money

Anthony Jackson played bass and co-wrote the tune!!

Thanks for your comments Gene – I was quoting Ken Cayre of Salsoul records. I assumed he knew what he was talking about!

Right it was A.Jackson