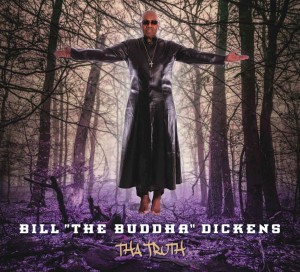

Tha Truth: An Interview with Bill Dickens

Many people have been introduced to the work of Bill Dickens through his jaw-dropping technique and finesse on his 7-string bass, but that’s not the whole story. Dickens, who started on drums at the tender age of 3, has been a songwriter since his teen years. His writing, producing, and arranging has gotten scored Billboard hits for several R&B artists, and now he’s putting the extent of abilities to his own debut solo album, aptly entitled Tha Truth.

“You’re seeing the real Bill Dickens: as an ensemble player, as a soloist, and as an arranger,” he says of the album. “People don’t really know I do all that until they hear the record. I call it ‘Tha Truth’ because it showcases me as I really am as opposed to what I’m perceived as.”

Dickens has led a diverse musical career with jazz and R&B at its core. He’s performed in concert with Chaka Khan, Pat Metheny, Stevie Wonder, Victor Wooten, Mary J. Blige, Randy Newman, and more. One of his first big breaks was a gig with renowned jazz pianist Gene Harris, which helped to expand his musical language and abilities. After spending time with the Ramsey Lewis Trio, Dickens quit bass for two years to focus on being a producer in the early ’90s. His latest gig has been as part of the Meters Experience with guitarist Leo Nocentelli.

His new album blends all the various aspects of music creation Dickens has mastered, resulting in a extremely varied record. Starting with the title track, each song explores genres from jazz to funk to rock.

We reached out to Dickens to get the scoop on Tha Truth, the changing record industry, his career and how he got started with extended range basses.

This album is a different direction for you in many ways.

This whole download thing, I’m not from that generation. I’m a record producer. I’m actually being retaught how to go about and perceive the whole thing with digital downloading and streaming, and how to go out and tell fans to go to iTunes and write reviews. A lot of this stuff caught me off guard and I didn’t really know at first, so it might have stagnated the release date of my record a little bit. It’s not the same as having a record deal and if you don’t come in at the top 20, all of the sudden you get a letter from the label saying you’re gone [laughs]! Those days are gone. This is totally different – you’re building a career. It could take several records for my first album to really generate any amount of sales.

This whole download thing, I’m not from that generation. I’m a record producer. I’m actually being retaught how to go about and perceive the whole thing with digital downloading and streaming, and how to go out and tell fans to go to iTunes and write reviews. A lot of this stuff caught me off guard and I didn’t really know at first, so it might have stagnated the release date of my record a little bit. It’s not the same as having a record deal and if you don’t come in at the top 20, all of the sudden you get a letter from the label saying you’re gone [laughs]! Those days are gone. This is totally different – you’re building a career. It could take several records for my first album to really generate any amount of sales.

It’s definitely new but I love it a lot better because it gives me all the creative control as the executive producer as well as working directly with the graphic artist and putting my own concepts together. So the pressure of labels doesn’t exist at all.

So this is really your baby. You’re in every aspect of it.

Yes, absolutely. It’s kind of like a deal that a rock star would get. It’s sort of like somebody had sold millions of records and the record company said, “You’ve got carte blanche. Just turn the record in and we’ll put it in the stores.” It’s wonderful, man. That aspect of it is just like, wow. I’m so glad it took me this long. It was a little painful, but it took this long to get to this point and I’m so happy about it.

What was painful about it?

Well, my record is so all over the place concept-wise. I’m really into orchestrating and strings mixed in with the hip-hop thing, plus having the contemporary and smooth jazz thing, then from that to rock, then from that to hardcore funk. There’s no set pattern. You can’t pinpoint it. So the painful part is when you’re searching for labels. Especially in the embryo stages of this album, I was searching for a label that would be open-minded enough to work with me on it. I wasn’t successful at all in doing that. You know, smooth jazz has a set category… pop, R&B, all of these genres have set categories. Well, this album doesn’t have a set category. It’s sixteen songs of music that is just all over the place.

That’s the great thing about signing with Ropeadope [Records]. They saw this as a great opportunity for them because their fans expect them to come out with product like this. It was a shock to me, and it was really enlightening.

So the painful part was the rejection of the project through the stages of trying to get it placed at a label, but the more successful and rewarding part was getting it placed, especially with a label that just won a Grammy with Snarky Puppy and Lalah Hathaway. I feel very fortunate. I feel like the bass world has been waiting on something from me for almost twenty years. Even my earlier years with Ramsey Lewis, we were trying to get a record out on me and we weren’t successful on that. When I had to quit playing bass and become a full-time record producer… I mean, I had a five million dollar studio I was working out of but my interest wasn’t into bass, per se. I was into production. The mindset I had was nowhere near this kind of situation.

Then my co-producer Dave Freeman put us in this situation where the band had to create the music on the spot. I’ve been sequencing on keyboards since 1986, so that’s something that I’m really at home as far as a [writing] platform I’m used to. In this case, it was all created on the spot with a band and I spent about two years cutting and pasting the parts to create songs. So what you’re hearing is all the stuff that was put together by jamming, and it was all done on 2-inch tape.

We recorded it at Steve Albini’s studio. He’s like the Quincy Jones of grunge music. So we recorded all of it at his studio and we used these extra large reels that I had never seen before. They’re used to have continuous tape rolling so that you can create without running out of tape. It was very interesting running that. Then we rented 96 tracks of Pro Tools, so it was like a 30-space rack of just a Pro Tools system running with the tape. It was a very different type of approach and a very different kind of album. Sonically, to me there’s not too many things that sound like that because we actually ran tape and we didn’t do just Pro Tools.

That sounds pretty complex. And this was over two years, right?

Yeah, well the editing was over two years. But it was a few years of me just working altogether on it. It wasn’t just editing, because I was overdubbing parts and redoing parts especially towards the end. I was doing a lot of stuff where I mixing in things from drum machines, but not sequenced – I was playing [the drum machine] live. There’s nothing that’s sequenced except for one song on the album which is “God’s Amazing Grace.” Everything else we played.

The song that I co-produced with Mike Gordon from Phish, that was all played live.

I wanted to ask how you got hooked up with Mike Gordon. I don’t think that’s a typical musical connection people would make.

[Part of it is] being part of the Meters Experience and having been able to play with all four of the original Meters members. It’s sort of something I’m not known for but it’s been the last four and half years that I’ve been doing it. I just got back from tour in Japan playing six sold out shows with the group The Icons of Funk, which consists of Fred Wesley on trombone from JB Horns, Bernie Worrell on keyboards from Parliament Funkadelic, Stanton Moore on drums from Galactica, Leo Nocentelli on guitar from the Meters, and myself.

Mike Gordon and I didn’t really hook up until later, and that came about through Leo Nocentelli. There was a show in the Bay Area, and the original four Meters opened up for Phish. I knew of Phish, but I knew nothing about their music. Leo introduced me to all four of them. Mike Gordon knew who I was. We hung out in his dressing room. I took my bass and he checked it out, then I checked out his bass. It just became an ongoing thing. He came to Chicago and said, “Bring some of your basses with you.” I brought three or four basses with me and we hung out for two days with him at the show.

The funny thing is that the first show I actually hung out because I had a show with the Meters Experience the next day in the Bay Area. I asked Mike if I could watch from the stage so he had his security put me on the side of the stage where there was nobody. I was there practically by myself watching them perform for 100,000 people. My mouth just hit the floor – I didn’t realize how big they were!

We kept in contact with each other, and eventually I told him I thought it would be a great idea to write something together. I told him I was working on my record but that I wasn’t signed and I was just working on it. He came up and said, “I have a song for you. I wrote it with my little girl. You may or may not like it, but check it out.” I checked out the song and I said, “I can do something with this.” I thought it kind of sounded like Sergeant Pepper, so I wanted it to sound like The Beatles. That’s the way I arranged it, then he did his thing on it. He played guitars, bass, and vocals on it. I did my George Benson stuff and played keyboards. A guy by the name of Jim Geffner played drums.

That tune is probably the one that’s left of center for the rest of the album. That one really, really stands out as something that you’d never expect from me.

You’ve been such a successful sideman and you’ve gotten so much work over the years. What made you decide to make your own album?

There’s a radio talk show host by the name of Dave Freeman. He’s also the co-producer of my album. He’s been part of my career since about 1979 or 1980. He put me on a record with a fusion group called Proteus. They were out of Chicago. That was one of the first albums I think he had produced. Over the years I did some live stuff with them.

But [the album] kind of just came out of thin air. I had been doing some live shows on my own and he brought the idea up to do a record. So I was thinking, “Wonderful. He’ll be the executive producer.” So I brought all the guys that I had been playing with. We had all been playing with Barry Manilow. So we all came together and I was thinking, “I’ve got some material.” We got to the studio [Freeman] didn’t want any of the material. He said, “I want you to just jam. Just put ideas together and we’ll cut and paste them.” I thought, “What? Really?”

It turned out to be phenomenal because after spending a couple years of putting stuff together and making songs with structure to them, I found I would have never been able to do this if I had just written it. It would have never come out like this.

That’s cool – just a totally different approach.

Exactly. As a matter of fact, one group that did all of their records like that throughout their career was the Ohio Players. All those records you hear are jam band tracks. There weren’t any songs that were written ahead. They jammed first that afterwards spliced all the music together, then wrote the lyrics. They did it backwards.

It’s been really enlightening to hear my music as an artist rather than me writing and producing somebody else. That’s the thing I’m really getting the joy out of. People are finally seeing me as an individual artist. And not only myself; look at Nathan East. He’s going through the roof. It’s a real nice time for us bass players to come out with a record, but I’m more about arranging and producing on this than I am trying to play solos.

From 1990 to 1995, I was basically entrenched in production work and doing house and dance music. I was working with a lot of famous dance producers so I was learning all about clubs and going into clubs to hear stuff that I had played to see the reaction of the people. I kind of took all that in to make my own thing. I figure if I can’t dance to this stuff then it doesn’t make sense to me. I love listening to music, but my first and most important thing for music is getting that feeling that makes me want to move around. Even with all the songs as odd as they sound, there’s always some sort of groove under there that really stamps that concept. I was just thinking that I wasn’t trying to be the bass player that everyone perceives me as. A lot of times, a lot of people call me this superfast bass player and then ignore or overlook all the records I played on. There’s a lot of stuff you don’t even know it’s me playing because it’s so simple. I think they overlook that for all the chops. Then there seems to be this group of people out there that chases me to criticize me. That’s the weird thing I think because I think they don’t understand theory. They think I’m playing all of these notes that don’t make sense, but if they understood theory, if they understood how to play through chord progressions, if they understood taking a drummer’s approach and playing paradiddles and all that kind of stuff then they would get it. I can understand especially for a lot of younger kids a lot of the stuff I’m doing is way over their heads.

I’m sure they talk about your 7-string, too.

Yeah, I’m one of the guys that’s carrying all the weight of that because at least from what I know, I’m the most visible bassist that has been carrying a 7-string bass since 1996. But I’ve had opportunities to play it for millions of people. Also, people that have bought my signature bass over the years have been very successful bass players that I would have never thought in a million years would be playing my bass.

I see that part of it and then inventing the 9-string with Bill Conklin, that tore the industry open as far as luthiers and different companies copying us. They started making 9-string, then it went up to 10, then 11. I’ve seen 15-string basses that make my 9-string bass look like a 4-string. It’s an interesting road to go down.

For bass players, especially if you’re in popular music, they kind of look at you funny once you get past five strings. A lot of people are looking for the vintage look with old Fender 4-strings. A lot of artists that I see out there with bassists, most of them are playing 4-strings. Some are playing five, but we had a good five or six year stretch where you saw a lot of 6-strings. Then you saw some 7-strings, and that’s kind of gone away because of the whole popular thing. When you get into popular music it’s all about image, too, you know.

I don’t want people to just go out and buy my bass and at the same time think they’re gonna get the biggest gig in the world. It doesn’t work like that. I want them to get my bass but I want them to have a Fender Jazz or Precision in their arsenal. These [7-string] basses were made for me because of what I do as a soloist, as a bassist and as a guitarist, but people have still been buying them. People have been buying them in the thousands, but I want people to understand that it’s great to have one, but make sure you have a 4-string.

How did you first get into the extended range bass thing?

I used to use Ken Smith basses. He would loan me basses to use when I was out with Ramsey Lewis, so every six months I was at his house. There was one situation that changed it all. I was a 4-string player at the time but I went to see Anthony Jackson’s group Eyewitness back in the early ’80s. He had a Ken Smith contrabass that he had made and it blew me away. Some of the stuff he was doing in the high register was astounding. I’d never seen anything like that. It had LED lights and tons of tone controls and volumes.

After seeing that, Ken was making another one of the contrabasses for a customer. I got a chance to try it out and I just lost my mind. I just said, “The things I could do on this would be devastating.” And at the same time I was so hurt because I couldn’t afford the bass. It was like $10,000. Ken came out to see me at a club in New York called Fat Tuesday’s where I was playing with Ramsey Lewis. Ramsey would always give me a solo by myself. When I first got the gig, he made me play a solo before 5,000 people all by myself. He and the drummer would leave the stage and I was left by myself. I didn’t know what to do, so I was kind of trained into all of that.

When I played that night with Ramsey, I played a song called “Willow Weep for Me.” Ken later told me that it was so emotional and it brought tears to his eyes. Of course I was playing on one of his basses. He told me come by the next day and to bring my bass. I figured he was going to loan me a new bass. He said, “Take this case and take it home with you. Don’t open it up until you get home.” I thought to myself, “Oh, it must be a 5-string.” Opened the bass and half of the headstock came out. I said, “Oh, it is a 5-string,” and I got real excited. I pulled the rest of the headstock out and it was the 6-string. I called Ken and told him he gave me the other customer’s bass, and he said, “No, no no. He doesn’t deserve it. You do.”

It was so beautiful. It had a tone control, a volume control, an on/off switch, a split coil switch, and then he put a new chip in the bass to make a parametric EQ that had 4K, 9K, 18K, and 21K. It was higher than Marcus Miller’s bass. Then there was a switch to go from active to passive. Then you had a Mu-tron in the bass that could sweep up or down. Then you had filter controls for the Mu-tron and the parametric EQ. I was like, “Oh my God!” I was like a kid in a candy store. I was also thinking to myself, “I’m gonna get myself fired on this gig!” [laughs]

Lo and behold, I remember trying the bass out for the first night. The moral of the story is that I went from playing a 4-string to a 6-string. I went to play the song and nothing was coming out of the bass. I thought it was short in the cord, but then I hit a string and thought, “Wait, why could I hear that note?” Then I realized my right hand was playing one string away from my left hand. I wasn’t used to playing more than 4-string on anything. It took me a while, but once I got it I had it.

As a matter of fact I used that bass to write a hit for Ramsey called “Bernice.” I played it as a solo piece that was kind of inspired by James Taylor. I would get standing ovations every night playing that song. One day Ramsey said, “I can’t take it no more, I gotta get this song on my record.” So it started out with me playing the pre-chorus and then came in with the band.

You also worked with pianist Gene Harris back in the day. What was that like for you?

Gene Harris was like my second father. He and I were extremely close. To make a long story short, I knew nothing about jazz or bebop until I met Gene Harris. The one thing that changed me about playing with Gene was watching he was playing like a Fender Rhodes and doing all this fast stuff, but it made sense. He knew what he was playing over the chords, it wasn’t just a bunch of mumbo jumbo. He actually introduced me to Monk Montgomery, who actually had the very first Fender. Monk had his own radio talk show in Vegas at the time and he came out and saw us play. At that time, I was a totally different person as a bass player. I was all about showmanship and dancing and jumping off stage and onto tables.

I remember Gene having an interview on Monk’s show. Monk said, “You know, you have a very interesting bass player. He jumped around. Sounds okay, you know, but to be honest he doesn’t play worth a shit.” [laughs] My mouth dropped, but he ended up giving me some lessons and really helped me out. The whole Gene Harris experience was a short experience, but it was phenomenal.

What’s something from your career that you think most fans may have missed?

There’s some overlooked history about me. There’s a song I recorded when I first started with Ramsey Lewis when I was about 23. Ramsey asked me if I could write. I used to be a songwriter for a production team when I was 16 years old. I got my first writer’s contract at 16, so I’ve always been a song writer. I wrote three songs that made it to Ramsey’s record, one of them being the single called “I Can’t Wait.” It was a song written by the drummer Frank Donaldson, Ramsey Lewis and myself. I found out later that this song was probably one of five songs in the history of R&B that had a bass solo on it. I used hear my record every day, several times a day on R&B radio. The only other people you had were were Louis Johnson from the Brothers Johnson, Bootsy Collins, Byron Miller with George Duke, and Larry Graham, but that was early ’70s and this song was in the early ’80s. I just wanted to say that because a lot of people don’t know where I came from. There’s a gap between when I left Ramsey and became a record producer and quit playing bass. A lot of people think that Victor Wooten discovered me, but I’ve been around.

Tha Truth was released on October 21st.

I wanted to be impressed, but OH MY GOD, that song “I Don’t Want To” was just awful. I thought I must have been listening to the wrong stream. Is that him singing, too?

The second song is much more bearable.

As he said, that’s Mike Gordon singing on “I Don’t Want To,” and it’s the most different of all the tracks on the album.