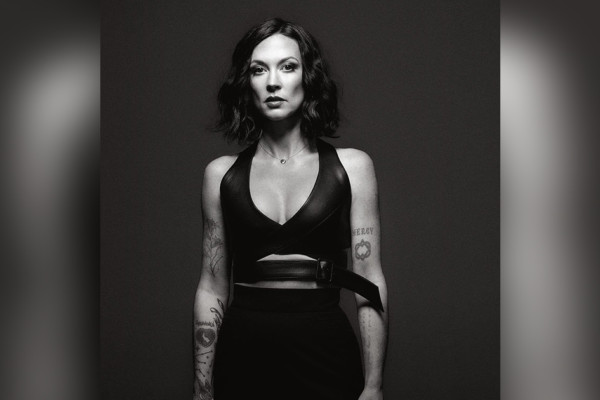

Reunions: An Interview With Jimbo Hart

From the first notes of Jason Isbell and The 400 Unit’s new album Reunions, it’s clear that the record is a deep experience. The singer-songwriter says his seventh studio album is full of ghosts. “Sometimes the songs are about the ghosts of people who aren’t around anymore, but they’re also about who I used to be, the ghost of myself,” Isbell says. “I found myself writing songs that I wanted to write fifteen years ago, but in those days, I hadn’t written enough songs to know how to do it yet. Just now have I been able to pull it off to my own satisfaction. In that sense it’s a reunion with the me I was back then.”

It’s in those same first notes of the opening track, “What’ve I Done to Help,” that bassist Jimbo Hart helps to establish the tone and feel of the record. That particularly melodic line serves as a musical hook to reinforce Isbell’s words. Whether it calls for more active or more subtle bass lines, Hart’s playing consistently serves the music.

It’s in those same first notes of the opening track, “What’ve I Done to Help,” that bassist Jimbo Hart helps to establish the tone and feel of the record. That particularly melodic line serves as a musical hook to reinforce Isbell’s words. Whether it calls for more active or more subtle bass lines, Hart’s playing consistently serves the music.

That makes sense when you start to dig into Hart’s story. Though he’s been a Nashville resident for several years, the bassist grew up in the rich music scene of Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The same Muscle Shoals that artists like Aretha Franklin, The Rolling Stones, Wilson Pickett, Paul Simon, and many more flocked to for its unique sound and session musicians like bassist David Hood. As such, his style is more of a conglomeration of soul and R&B than what one may think of as a typical “Nashville” sound. His time between the two cities has also helped him become a keen studio engineer and self-proclaimed gear nut.

As seriously as he takes the music, Hart’s hilarious quips are just as much a part of his character. There’s an entire Twitter profile dedicated to his Yogi Berra-esque one-liners like, “You take more than two lefts, you goin’ back where you started from.”

In our conversation, we talk about crafting the right bass line for a song, how he got that perfect old school tone on “What’ve I Done to Help,” and what it was like growing up in Muscle Shoals. He also revealed what famous metalhead gave him his prized Sadowsky bass.

Reunions is available now on CD, vinyl and as a digital download (iTunes and Amazon MP3).

I really love the bass line to “What’ve I Done to Help” – it’s so lyrical.

Thank you. A lot of it is following Jason, then trying to draw from some different places in R&B. There’s definitely that “Inner City Blues” nod, but there are other things, too. My headspace was in the era of what David Hood did with Bobby Womack like “Across 110th Street.” The lyric and the melody just lent itself to go there. I followed it and nobody said, “Hey! What are you doing?” so I just kept following it. [laughs] That’s usually how it goes with us. If something’s wrong, somebody will say, “Can you do something else?” We’re pretty straight up about it. Normally we don’t really have to say much.

Do you get much direction?

We all sit around a table and Jason will play us the song. This time we had the advantage of having a lyric sheet. Usually he doesn’t do that, you just hear it once and take notes before you sit down with your instrument for a little bit. Generally, there are times when they have to switch out microphones or change guitars or something, so there’s a little space between hearing it for the first time and picking up the instrument and charging forward, so to speak. Every song is different and has its own approach. We all know when it’s working and when something needs to be different. It’s really easy and organic.

So do you write your bass lines in the studio or do you have a month ahead of time to work on them?

No, it’s in the studio, normally on the fly. We go for a real gut thing. Also, being from Muscle Shoals, that’s just kind of the way they work. If you know the numbers [system], it’s fairly simple. You just hop on board, get in time, make sure you’re in tune and don’t stink. When your gut tells you to “play this little thing here” or “don’t play anything here,” you should be very wary of that voice because that’s very honest.

We tend to go with the first impression. If you take too long, you get away from the point. We try not to put too much thought into it because you’re still going to be thinking about it [every time you play it]. If you play it in the future then you’re still thinking about it and never really “in” it.

That concept, over-production, seems like a real problem in music nowadays.

It’s easy to do. I’m guilty of doing it myself. I’ve produced some things where I maybe added one too many percussion tracks here and there. In the moment I felt like I was following something. But I know what you mean. Some things are a little too perfect. It takes away the honesty when everything is absolutely pitch-perfect or perfectly in time. We’re human beings. Like Larry Graham said, “Your heart is not set at 120bpm.” It might be at 96 for a minute, then 102, then 145. Then some days its 360 all day long! You can’t really quantify an emotion. I don’t think you can be honest if you quantify things musically too much.

What was growing up around Muscle Shoals like? Was David Hood a part of your story?

Yeah, David is definitely part of my story. I wouldn’t run into him a lot locally around town, but when there were get-togethers I would. Scott Boyer, who was in the band Cowboy and a big part of Capricorn Records early on, was a Muscle Shoals guy. His son and I were in a funk and soul band together for a long time. Scott would have these get-togethers at the lake house and there would be all these musicians. Oddly, the only one of the Swampers I’d run into in public all the time would be Pete Carr. He played guitar on lots of stuff. He and Eddie Hinton were two great players from that era. I would run into Pete all the time at Walmart. Very friendly fella.

Anyway, David would be at these parties. They’d find out I was there and he’d ask me to sit in. I’d play two or three songs then he’d come up to me and say, “Man, I’ve gotta go. I gotta do something in the morning. Just put that bass on the stand when you leave and I’ll make sure it’s alright.” You can’t say no to that. It just left me in the seat for the rest of the evening. In hindsight, what a gift [that was]. You really learn on the spot. There were no charts; it’s just dudes with guitars, a keyboard player, and some drums. And a whole bunch of microphones and a whole bunch of other musicians in the place that are watching you and wanting you to prove yourself. You have to learn how to mess up and do it gracefully. You know that old adage about if you make a mistake, just do it again two more times and it’s right? I do that shit all the time! [laughs] I’ll just keep doing it again.

Were you influenced to get into music from that scene?

No, not necessarily. My dad played guitar and would sit around and play songs. He never really wanted anyone to hear him but me. My mom and dad got divorced, then my dad married a lady whose family was very musical. They would get together on the weekends and play all sorts of stuff: Chuck Berry songs, Beatles songs, John Prine songs. My Uncle Bob had a Gibson Ripper bass and one of those really tall Kustom amps. It took up the whole corner of the den. He was a really tall guy, so there was always just a presence coming from the bass that I gravitated to. I also noticed whenever he played you could hear the windows rattling. When he stopped, there was this absence of that presence. I always thought, “That’s so powerful. This guy is shaking the house – literally.” One night he said, “Here, hold this. I’ve gotta get a beer” and handed me the bass. I put it on my lap and turned the volume knob all the way up. I hit the E string and the house just shook. I said, “OK!” It was like showing a duck water. It’s pretty much run everything ever since. Cheers to Uncle Bob!

So it’s just a coincidence that you grew up around such a fertile music scene.

I honestly thought that everybody’s family was musical in Muscle Shoals. That’s just what everybody did. When my dad wasn’t working in the garage on the weekends, he’d sit on the patio and play the guitar. There was a house two doors down from me where the kids had a band. There was a little bar behind my house that I would sneak out and go to whenever bands I liked would play there. It was back in the day when you could be 12 or 13 years old and slip the doorman five or ten bucks and he’d let you in. You’d go in the corner and be small and not cause any trouble or you’d get kicked out. I would sit in the corner and watch the Fiddleworms, LSD-30, or Max Russell’s Blues Band. It was just great. I’m really grateful for that, too. I don’t think these days that a place could get away with that.

What are you doing to keep yourself busy during the quarantine?

My lady and I dug a garden in our backyard. We recently built a paver patio. We had to do a lot of digging and tamping. And digging. And digging. And digging. We moved a lot of dirt. It was good. We’re keeping ourselves occupied. I’m working on some projects here in my studio here and there. I’m just about ready to start recording a process for a Cole Gallagher from Los Angeles.

You have a pretty serious studio. Do you have any tips for guys that are trying to record at home to get better sounding bass?

There’s a lot of little technical things about it. The differences in DI’s and preamps come into play a lot, especially if you’re not using an amp. I recently got an old Urei 315 DI. It’s got the Urei transformer like an 1176. It sounds really good with a P-bass or with an active bass like my Sadowsky. A lot of times an active DI or a passive DI will change the personality of the bass. It’s all about impedance matching and gain stage. Gain stage is huge, especially when you’re recording bass. I still have my old Noble DI and I still love it a whole, whole lot, but it’s locked up in our storage unit and I can’t get to it. It’s driving me crazy.

There’s a lot of little technical things about it. The differences in DI’s and preamps come into play a lot, especially if you’re not using an amp. I recently got an old Urei 315 DI. It’s got the Urei transformer like an 1176. It sounds really good with a P-bass or with an active bass like my Sadowsky. A lot of times an active DI or a passive DI will change the personality of the bass. It’s all about impedance matching and gain stage. Gain stage is huge, especially when you’re recording bass. I still have my old Noble DI and I still love it a whole, whole lot, but it’s locked up in our storage unit and I can’t get to it. It’s driving me crazy.

What are you running bass-wise on the new record? “What’ve I Done to Help” sounds real old school, like maybe flatwounds and some foam.

Yep, exactly. That was recorded with my ’63 P-Bass that was actually my band director’s bass. I used it in high school for some things, but I had a ’70s P-bass back then. Whenever it was raining or something, we’d say, “Oh, just take the old one instead.” [laughs] It was before eBay. Guys that play know, but it was a well-kept secret that the older the bass is the better it is. In my mind, I thought newer was better. Back then, you could get a ’60s or ’70s P-bass off of a cat for a couple hundred dollars. It wasn’t rare at all. Now for that same bass you can basically ask whatever you want for it.

So you’re right – I used that bass with flatwounds and a piece of foam velcroed to the bottom of the bridge cover, which was then screwed down overtop of [the strings]. I don’t think the foam really clamps down on it too much. I’ve seen foam where it’s really shoved in there and too tight and kills every bit of sustain. I like sustain. I think the left hand has more to do with it than the foam or any of that stuff, but the foam does help sometimes. It makes the string act a little different.

I know I used my black Sadowsky Will Lee model that Jason Newsted gave me on two or three songs. I also used two different Kala U-Basses on the record. One has the black rubber strings and the other has their new flatwound over rubber core strings. Talk about fun, man! You plug it up and it sounds a lot like a P-bass, especially with a nice tube preamp that slows down the piezo transient a little bit. But you get the fun of playing a U-bass.

How did you get to know Jason Newsted, or at least get a bass from him?

He came to a New Year’s Eve show that we did with John Prine at the Grand Ole Opry a few years back. We all met him then, and he just started coming to shows and hanging out with us. After a while we were texting. He’s my homie now, man. We’re pretty tight. I love the dude.

So he just showed up to this gig in Oakland and long story short pulled this case out from behind our wardrobe case. He said, “I’ve seen four or five of your shows and I can’t sit still, so I always have to go listen all over the room. Everything sounds amazing, but the kick drum is always tuned really low. It sounds awesome, but because of that you lose string definition in the first position. This will fix it.” I said, “Are you serious?” He said, “Yeah, rock and roll!” because he’s still like that.

I’ll be damned if this thing hasn’t become my favorite bass. It’s a utilitarian factor. It’s so well made and it’s so consistent. Every time I pick it up it gives back. Then Jason introduced me to Roger Sadowsky, so I got to make a new friend with Roger. He’s a sweet dude and I really like his strings.

Coming from a P-bass to something like that is like driving a Mustang LX for all your life and then someone hands you a BMW 3-series. You have to learn how to drive it fast before you can learn to drive it slow. I was using a lot of the EQ and doing way too much on the bass that I didn’t need to be doing. Looking at it now, I usually use the EQ flat and it’s all about the tone control.

When you’re recording, did your run amps or just direct?

Most of the time it was direct with my Noble DI. They would do all the other stuff after the fact. I think [engineer Gena Johnson] told me they put an LA2A on me in the control room and never touched it. I don’t know how much they messed with it in the mix, though. I wasn’t there for that. [Producer Dave Cobb] has a lot of really choice amplifiers and outboard gear. When we recorded it, he had just bought a brand new API console that’s the size of Jay-Z’s yacht or something. It sounds amazing. API stuff sounds so good you can fart into it and it’s gonna rock, man.

When you’ve got gear like that, it’s easy to be inspired. Then when you are inspired the sound comes. It’s not always about the gear, but the gear definitely helps get you there faster. We were fortunate in that regard. So hats off to Mr. Cobb on that call. It was a hell of a purchase.

Do you consider yourself a “less is more” kind of guy?

No, not necessarily. When there obviously needs to be less, then absolutely it should be less. I don’t consider it playing less as much as I consider it creating more space. A lot of my bass lines aren’t fewer notes. I tend to be note-y and I fight it because it doesn’t translate that well through speakers to be super note-y on an instrument that doesn’t move speakers very quickly. I try to be aware of that.

I think I just follow the song. If the song wants you to play less, then play as little as you can. Take it to the extreme. But if the song wants you to play a little more, throw everything at it and sculpt it back to what it needs to be. You have to find the outer limits of what you want are before you can hone it down. It usually takes me three to five takes. Sometimes I’ll do two or three takes then walk away to do something else for half an hour, then come back and do another one. Sometimes that one is way better, and sometimes it just gets worse. [laughs] At least it gives you a minute to marinate on it. It lets everything sink in. It’s about letting [your heart] and [your head] just enjoy dinner, so to speak.

I think this album sounds incredible. It’s one of the best sounding records we’ve ever done and I’m so proud of it.

The bass lines really drive it home, like on “Be Afraid,” in the beginning when you just sneak that harmonic in. Bass nerds hear that but it just fits so perfectly.

That’s that Newsted bass. It’s got a drop key on it, so I just dropped it and it lent itself to its own sort of thing. That song is really unique and going to be its own challenge in the live sense because there is the bass line, but then there’s also a sub keyboard that’s on there as well. I’m wondering if it’s time to bust out the Taurus pedal! I am afraid of that. If you step on the wrong pedal, it’s wrong. Way wrong – deep down wrong. Make people sick kind of wrong. So I’m wondering how I’m going to pull that off. Maybe there’s a way to synthesize it with the bass or make it with a parallel line and an octave pedal.

Who runs the Jimbo Hart Says Twitter account? I really appreciate those quotes.

The band. I don’t run it. I don’t look at it very much, but I looked at it a few weeks ago and laughed so hard I almost pissed myself. I think it’s hilarious.

Do you remember saying that stuff?

Oh yeah, I remember saying it all. I say some pretty dumb shit to get people to laugh. I think laughter is so much better than any other emotion because it’s very honest. It’s uplifting and positive. If you make someone laugh, you just know everything is alright. I try to be silly more often than not. If I’m not silly then no one else is going to be silly. If you can’t be silly, you can’t really live.